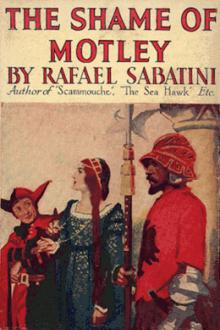

The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

An eventful year in the history of the families of Sforza and Borgia was that year of grace 1497.

Spring came, and ere it had quite grown to summer we had news of the assassination of the Duke of Gandia, and the tale that he was done to death by his elder brother, Cesare Borgia; a tale which seemed to lack for reasonable substantiation, and which, despite the many voices that make bold to noise it broadcast, may or may not be true.

In that same month of June messages passed between Rome and Pesaro, and gradually the burden of the messages leaked out in rumours that Pope Alexander and his family were pressing the Lord Giovanni to consent to a divorce. At last he left Pesaro again; this time to journey to Milan and seek counsel with his powerful cousin, Lodovico, whom they called “The Moor.” When he returned he was more sulky and downcast than ever, and at Gradara he lived in an isolation that had been worthy of a hermit.

And thus that miserable year wore itself out, and, at last, in December, we heard that the divorce was announced, and that Lucrezia Borgia was the Tyrant of Pesaro’s wife no more. The news of it and the reasons that were put forward as having led to it were roared across Italy in a great, derisive burst of laughter, of which the Lord Giovanni was the unfortunate and contemptible butt.

And now, lest I grow tedious and weary you with this narrative of mine, it may be well that I but touch with a fugitive pen upon the events of the next three years of the history of Pesaro.

Early in 1498 the Lord Giovanni showed himself once more abroad, and he seemed again the same weak, cruel, pleasure-loving tyrant he had been before shame overtook him and drove him for a season into hiding. Madonna Paola and her brother, Filippo di Santafior, remained in Pesaro, where they now appeared to have taken up their permanent abode. Madonna Paola— following her inclinations—withdrew to the Convent of Santa Caterina, there to pursue in peace the studies for which she had a taste, whilst her splendid, profligate brother became the ornament—the arbiter elegantiarum—of our court.

Thus were they left undisturbed; for in the cauldron of Borgia politics a stew was simmering that demanded all that family’s attention, and of whose import we guessed something when we heard that Cesare Borgia had flung aside his cardinalitial robes to put on armour and give freer rein to the boundless ambition that consumed him.

With me life moved as if that winter excursion and adventure had never been. Even the memory of it must have faded into a haze that scarce left discernible any semblance of reality, for I was once again Boccadoro, the golden-mouthed Fool, whose sayings were echoed by every jester throughout Italy. My shame that for a brief season had risen up in arms seemed to be laid to rest once more, and I was content with the burden that was mine. Money I had in plenty, for when I pleased him the Lord Giovanni’s vails were often handsome, and much of my earnings went to my poor mother, who would sooner have died starving than have bought herself bread with those ducats could she have guessed at what manner of trade Lazzaro Biancomonte had earned them.

The Lord Giovanni was a frequent visitor at the Convent of Santa Caterina, whither he went, ever attended by Filippo di Santafior, to pay his duty to his fair cousin. In the summer of 1500, she being then come to the age of eighteen, and as divinely beautiful a lady as you could find in Italy, she allowed herself to be persuaded by her brother—who, I make no doubt had been, in his turn, persuaded by the Lord of Pesaro—to leave her convent and her studies, and to take up her life at the Sforza Palace, where Filippo held by now a sort of petty court of his own.

And now it fell out that the Lord Giovanni was oftener at the Palace than at the Castle, and during that summer Pesaro was given over to such merrymaking as it had never known before. There was endless lute-thrumming and recitation of verses by a score of parasite poets whom the Lord Giovanni encouraged, posing now as a patron of letters; there were balls and masques and comedies beyond number, and we were as gay as though Italy held no Cesare Borgia, Duke of Valentinois, who was sweeping northward with his all-conquering flood of mercenaries.

But one there was who, though the very centre of all these merry doings, the very one in whose honour and for whose delectation they were set afoot, seemed listless and dispirited in that boisterous crowd. This was Madonna Paola, to whom, rumour had it, that her kinsman, the Lord Giovanni, was paying a most ardent suit.

I saw her daily now, and often would she choose me for her sole companion; often, sitting apart with me, would she unburden her heart and tell me much that I am assured she would have told no other. A strange thing may it have seemed, this confidence between the Fool and the noble Lady of Santafior—my Holy Flower of the Quince, as in my thoughts I grew to name her. Perhaps it may have been because she found me ever ready to be sober at her bidding, when she needed sober company as those other fools—the greater fools since they accounted themselves wise—could not afford her.

That winter adventure betwixt Cagli and Pesaro was a link that bound us together, and caused her to see under my motley and my masking smile the true Lazzaro Biancomonte whom for a little season she had known. And when we were alone it had become her wont to call me Lazzaro, leaving that other name that they had given me for use when others were at hand. Yet never did she refer to my condition, or wound me by seeking to spur me to the ambition to become myself again. Haply she was content that I should be as I sas, since had I sought to become different it must have entailed my quitting Pesaro, and this poor lady was so bereft of friends that she could not afford to lose even the sympathy of the despised jester.

It was in those days that I first came to love her with as pure a flame as ever burned within the heart of man, for the very hopelessness of it preserved its holy whiteness. What could I do, if I would love her, but love her as the dog may love his mistress? More was surely not for me— and to seek more were surely a madness that must earn me less. And so, I was content to let things be, and keep my heart in check, thanking God for the mercy of her company at times, and for the precious confidences she made me, and praying Heaven—for of my love was I grown devout—that her life might run a smooth and happy course, and ready, in the furtherance of such an object, to lay down my own should the need arise. Indeed there were times when it seemed to me that it was a good thing to be a Fool to know a love of so rare a purity as that—such a love as I might never have known had I been of her station, and in such case as to have hoped to win her some day for my own.

One evening of late August, when the vines were heavy with ripe fruit, and the scent of roses was permeating the tepid air, she drew me from the throng of courtiers that made merry in the Palace, and led me out into the noble gardens to seek counsel with me, she said, upon a matter of gravest moment. There, under the sky of deepest blue, crimsoning to saffron where the sun had set, we paced awhile in silence, my own senses held in thrall by the beauty of the eventide, the ambient perfumes of the air and the strains of music that faintly reached us from the Palace. Madonna’s head was bent, and her eyes were set upon the ground and burdened, so my furtive glance assured me, with a gentle sorrow. At length she spoke, and at the words she uttered my heart seemed for a moment to stand still.

“Lazzaro,” said she, “they would have me marry.”

For a little spell there was a silence, my wits seeming to have grown too numbed to attempt to seek an answer. I might be content, indeed, to love her from a distance, as the cloistered monk may love and worship some particular saint in Heaven; yet it seems that I was not proof against jealousy for all the abstract quality of my worship.

“Lazzaro,” she repeated presently, “did you hear me? They would have me marry.”

“I have heard some such talk,” I answered, rousing myself at last; “and they say that it is the Lord Giovanni who would prove worthy of your hand.”

“They say rightly, then,” she acknowledged. “The Lord Giovanni it is.”

Again there was a silence, and again it was she who broke it.

“Well, Lazzaro?” she asked. “Have you naught to say?”

“What would you have me say, Madonna? If this wedding accords with your own wishes, then am I glad.”

“Lazzaro, Lazzaro! you know that it does not.”

“How should I know it, Madonna?”

“Because your wits are shrewd, and because you know me. Think you this petty tyrant is such a man as I should find it in my heart to conceive affection for? Grateful to him am I for the shelter he has afforded us here; but my love—that is a thing I keep, or fain would keep, for some very different man. When I love, I think it will be a valorous knight, a gentleman of lofty mind, of noble virtues and ready address.”

“An excellent principle on which to go in quest of a husband, Madonna mia. But where in this degenerate world do you look to find him?”

“Are there, then, no such men?”

“In the pages of Bojardo and those other poets whom you have read too earnestly there may be.”

“Nay, there speaks your cynicism,” she chided me. “But even if my ideals be too lofty, would you have me descend from the height of such a pinnacle to the level of the Lord Giovanni—a weak-spirited craven, as witnesses the manner in which he permitted the Borgias to mishandle him; a cruel and unjust tyrant, as witnesses his dealing with you, to seek no further instances; a weak, ignorant, pleasure-loving fool, devoid of wit and barren of ambition? Such is the man they would have me wed. Do not tell me, Lazzaro, that it were difficult to find a better one than this.”

“I do not mean to tell you that. After all, though it be my trade to jest, it is not my way to deal in falsehood. I think, Madonna, that if we were to have you write for us such an appreciation of the High and Mighty Giovanni Sforza, you would leave a very faithful portrait for the enlightenment of posterity.”

“Lazzaro, do not jest!” she cried. “It is your help I need. That is the reason why I am come to you with the tale of what they seek to force me into doing.”

“To force you?” I cried. “Would they dare so much?”

“Aye, if I resist them further.”

“Why, then,” I answered, with a ready laugh, “do not resist them further.”

“Lazzaro!” she cried, her accents telling of a spirit wounded by what she accounted a

Comments (0)