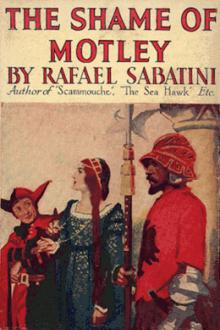

The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

On that “Te Deum” I finished softly, and as my voice ceased and the vibration of my last chord melted away, a thunder of applause was my reward.

Men leapt from their chairs in their enthusiasm, and crowded round the table on which I was perched, whilst, when presently I sprang down, one noble woman kissed me on the lips before them all, saying that my mouth was indeed a mouth of gold.

Madonna Paola was leaning towards the Lord Giovanni, her eyes shining with excitement and filmed with tears as they proudly met his glance, and I knew that my song had but served to endear him the more to her by causing her to realise more keenly the brave qualities of the adventure that I sang. The sight of it almost turned me faint, and I would have eluded them and got away as I had come but that they lifted me up and bore me so to the table at which the Lord Giovanni sat. He smiled, but his face was very pale. Could it be that I had touched him? Could it be that I had driven the iron into his soul, and that he could not bear to confront me, knowing what a dastard I must deem him?

The splendid Filippo of Santafior had risen to his feet, and was waving a white, bejewelled hand in an imperious demand for silence. When at last it came he spoke, his voice silvery and his accents mincing.

“Lord of Pesaro; I demand a boon. He who for years has suffered the ignominy of the motley is at last revealed to us as a poet of such magnitude of soul and richness of expression that he would not suffer by comparison with the great Bojardo or tim greater Virgil. Let him be stripped for ever of that hideous garb he wears, and let him be treated, hereafter, with the dignity his high gifts deserve. Thus shall the day come when Pesaro will take honour in calling him her son.”

Loud and long was the applause that succeeded his words, and when at last it had died down, the Lord Giovanni proved equal to the occasion, like the consummate actor that he was.

“I would,” said he, “that these high gifts, of which to-night he has afforded proof, could have been employed upon a worthier subject. I fear me that since you have heard his epic you will be prone to overestimate the deed of which it tells the story. I would, too, my friends,” he continued, with a sigh, “that it were still mine to offer him such encouragement as he deserves. But I am sorely afraid that my days in Pesaro are numbered, that my sands are all but run—at least, for a little while. The conqueror is at our gates, and it would be vain to set against the overwhelming force of his numbers the handful of valiant knights and brave soldiers that to-day opposed and scattered his forerunners. It is my intention to withdraw, now that my honour is safe by what has passed, and that none will dare to say that it was through fear that I fled. Yet my absence, I trust, may be but brief. I go to collect the necessary resources, for I have powerful friends in this Italy whose interests touching the Duca Valentino go hand in hand with mine, and who will, thus, be the readier to lend me assistance. Once I have this, I shall return and then—woe to the vanquished!”

The tide of enthusiasm that had been rising as he spoke, now overflowed. Swords leapt from their scabbards—mere toy weapons were they, meant more for ornament than offence, yet were they the earnest of the stouter arms those gentlemen were ready to wield when the time came. He quieted their clamours with a dignified wave of the hand.

“When that day comes I shall see to it that Boccadoro has his deserts. Meanwhile let the suggestion of my illustrious cousin be acted upon, and let this gifted poet be arrayed in a manner that shall sort better with the nobility of his mind that to-night he has revealed to us.

Thus was it that I came, at last, to shed the motley and move among men garbed as themselves. And with my outward trappings I cast off, too, the name of Boccadoro, and I insisted upon being known again as Lazzaro Biancomonte.

But in so far as the Court of Pesaro was concerned, this new life upon which I was embarked was of little moment, for on the Tuesday that followed that first Sunday in October of such momentous memory, the Lord Giovanni’s Court passed out of being.

It came about with his flight to Bologna, accompanied by the Albanian captain and his men, as well as by several of the knights who had joined in Sunday’s fray. Ardently, as I came afterwards to learn, did he urge Madonna Paola and her brother to go with them, and I believe that the lady would have done his will in this had not the Lord Filippo opposed the step. He was no warrior himself, he swore—for it was a thing he made open boast of, affecting to despise all who followed the coarse trade of arms—and, as for his sister, it was not fitting that she should go with a fugitive party made up of a handful of knights and some fifty rough mercenaries, and be exposed to the hardships and perils that must be theirs. Not even when he was reminded that the advancing conqueror was Cesare Borgia did it affect him, for despite his shallow, mincing ways, and his paraded scorn of war and warriors, the Lord Filippo was stout enough at heart. He did not fear the Borgia, he answered serenely, and if he came, he would offer him such hospitality as lay within his power.

He came at last, did the mighty Cesare, although between his coming and Giovanni’s flight a full fortnight sped. As for myself, I spent the time at the Sforza Palace, whither the Lord Filippo had carried me as his guest, he being greatly taken with me and determined to become my patron. We had news of Giovanni, first from Bologna and later from Ravenna, whither he was fled. At first he talked of returning to Pesaro with three hundred men he hoped to have from the Marquis of Mantua. But probably this was no more than another piece of that big talk of his, meant to impress the sorrowing and repining Madonna Paola, who suffered more for him, maybe, than he suffered himself.

She would talk with me for hours together of the Lord Giovanni, of his mental gifts, and of his splendid courage and military address, and for all that my gorge rose with jealousy and with the force of this injustice to myself, I held my peace. Indeed, indeed, it was better so. For all that I was no longer Boccadoro the Fool, yet as Lazzaro Biancomonte, the poet, I was not so much better that I could indulge any mad aspirations of my own such as might have led me to betray the dastard who had arrayed his craven self in the peacock feathers of my achievements.

In the course of the confidence with which the Lord Filippo honoured me I made bold, on the eve of Cesare’s arrival, to suggest to him that he should remove his sister from the Palace and send her to the Convent of Santa Caterina whilst the Borgia abode in the town, lest the sight of her should remind Cesare of the old-time marriage plans which his family had centred round this lady, and lead to their revival. Filippo heard me kindly, and thanked me freely for the solicitude which my counsel argued. For the rest, however, it was a counsel that he frankly admitted he saw no need to follow.

“In the three years that are sped since the Holy Father entertained such plans for the temporal advancement of his nephew Ignacio, the fortunes of the House of Borgia have so swollen that what was then a desirable match for one of its members is now scarcely worthy of their attention. I do not think,” he concluded, “that we have the least reason to fear a renewal of that suit.”

It may be that I am by nature suspicious and quick to see ignoble motives in men’s actions, but it occurred to me then that the Lord Filippo would not be so greatly put about if indeed the Borgias were to reopen negotiations for the bestowing of Madonna Paola’s hand upon the Pope’s nephew Ignacio. That swelling of the Borgia fortunes which in the three years had taken place and which, he contended, would render them more ambitious than to seek alliance with the House of Santafior, rendered them, nevertheless, in his eyes a more desirable family to be allied with than in the days when he had counselled his sister’s flight from Rome. And so, I thought, despite what stood between her and the Lord Giovanni, Filippo would know no scruple now in urging her into an alliance with the House of Borgia, should they manifest a willingness to have that old affair reopened.

On the 29th of that same month of October, Cesare arrived in Pesaro. His entry was a triumphant procession, and the orderliness that prevailed among the two thousand men-at-arms that he brought with him was a thing that spoke eloquently for the wondrous discipline enforced by this great condottiero.

The Lord Filippo was among those that met him, and like the time-server that he was, he placed the Sforza Palace at his disposal.

The Duca Valentino came with his retinue and the gentlemen of his household, among whom was ever conspicuous by his great size and red ugliness the Captain Ramiro del’ Orca, who now seemed to act in many ways as Cesare’s factotum. This captain, for reasons which it is unnecessary to detail, I most sedulously avoided.

On the evening of his arrival Cesare supped in private with Filippo and the members of Filippo’s household—that is to say, with Madonna Paola and two of her ladies, and three gentlemen attached to the person of the Lord Filippo. Cesare’s only attendants were two cavaliers of his retinue, Bartolomeo da Capranica, his Field-Marshal, and Dorio Savelli, a nobleman of Rome.

Cesare Borgia, this man whose name had so terrible a sound in the ears of Italy’s little princelings, this man whose power and whose great gifts of mind had made him the subject of such bitter envy and fear, until he was the best-hated gentleman in Italy—and, therefore, the most calumniated— was little changed from that Cardinal of Valencia, in whose service I had been for a brief season. The pallor of his face was accentuated by the ill-health in which he found himself just then, and the air of feverish restlessness that had always pervaded him was grown more marked in the years that were sped, as was, after all, but natural, considering the nature of the work that had claimed him since he had deposed his priestly vestments. He was splendidly arrayed, and he bore himself with an imperial dignity, a dignity, nevertheless, tempered with graciousness and charm, and as I regarded him then, it was borne in upon me that no fitter name could his godfathers have bestowed on him than that of Cesare.

The Lord Filippo exerted all his powers worthily to entertain his noble and illustrious guest, and by his extreme, almost servile affability it not

Comments (0)