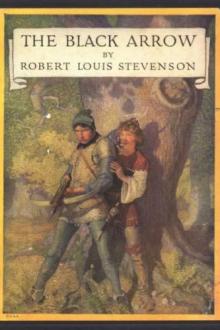

The Black Arrow - Robert Louis Stevenson (positive books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Robert Louis Stevenson

- Performer: -

Book online «The Black Arrow - Robert Louis Stevenson (positive books to read TXT) 📗». Author Robert Louis Stevenson

“Saints!” she cried, “but what a noise ye keep! Can ye not speak in compass? And now, Joanna, my fair maid of the woods, what will ye give your gossip for bringing you your sweetheart?”

Joanna ran to her, by way of answer, and embraced her fierily.

“And you, sir,” added the young lady, “what do ye give me?”

“Madam,” said Dick, “I would fain offer to pay you in the same money.” “Come, then,” said the lady, “it is permitted you.”

But Dick, blushing like a peony, only kissed her hand.

“What ails ye at my face, fair sir?” she inquired, curtseying to the very ground; and then, when Dick had at length and most tepidly embraced her, “Joanna,” she added, “your sweetheart is very backwards under your eyes; but I warrant you, when first we met, he was more ready. I am all black and blue, wench; trust me never, if I be not black and blue! And now,” she continued, “have ye said your sayings? for I must speedily dismiss the paladin.”

But at this they both cried out that they had said nothing, that the night was still very young, and that they would not be separated so early.

“And supper?” asked the young lady. “Must we not go down to supper?”

“Nay, to be sure!” cried Joan. “I had forgotten.”

“Hide me, then,” said Dick, “put me behind the arras, shut me in a chest, or what ye will, so that I may be here on your return. Indeed, fair lady,” he added, “bear this in mind, that we are sore bested, and may never look upon each other’s face from this night forward till we die.”

At this the young lady melted; and when, a little after, the bell summoned Sir Daniel’s household to the board, Dick was planted very stiffly against the wall, at a place where a division in the tapestry permitted him to breathe the more freely, and even to see into the room.

He had not been long in this position, when he was somewhat strangely disturbed. The silence in that upper storey of the house, was only broken by the flickering of the flames and the hissing of a green log in the chimney; but presently, to Dick’s strained hearing, there came the sound of some one walking with extreme precaution; and soon after the door opened, and a little black-faced, dwarfish fellow, in Lord Shoreby’s colours, pushed first his head, and then his crooked body, into the chamber. His mouth was open, as though to hear the better; and his eyes, which were very bright, flitted restlessly and swiftly to and fro. He went round and round the room, striking here and there upon the hangings; but Dick, by a miracle, escaped his notice. Then he looked below the furniture, and examined the lamp; and, at last, with an air of cruel disappointment, was preparing to go away as silently as he had come, when down he dropped upon his knees, picked up something from among the rushes on the floor, examined it, and, with every signal of delight, concealed it in the wallet at his belt.

Dick’s heart sank, for the object in question was a tassel from his own girdle; and it was plain to him that this dwarfish spy, who took a malign delight in his employment, would lose no time in bearing it to his master, the baron. He was half tempted to throw aside the arras, fall upon the scoundrel, and, at the risk of his life, remove the tell-tale token. And while he was still hesitating, a new cause of concern was added. A voice, hoarse and broken by drink, began to be audible from the stair; and presently after, uneven, wandering, and heavy footsteps sounded without along the passage.

“What make ye here, my merry men, among the greenwood shaws?” sang the voice. “What make ye here? Hey! sots, what make ye here?” it added, with a rattle of drunken laughter; and then, once more breaking into song:

Fat Friar John, ye friend o’ mine—

If I should eat, and ye should drink,

Who shall sing the mass, d’ye think?”

Lawless, alas! rolling drunk, was wandering the house, seeking for a corner wherein to slumber off the effect of his potations. Dick inwardly raged. The spy, at first terrified, had grown reassured as he found he had to deal with an intoxicated man, and now, with a movement of cat-like rapidity, slipped from the chamber, and was gone from Richard’s eyes.

What was to be done? If he lost touch of Lawless for the night, he was left impotent, whether to plan or carry forth Joanna’s rescue. If, on the other hand, he dared to address the drunken outlaw, the spy might still be lingering within sight, and the most fatal consequences ensue.

It was, nevertheless, upon this last hazard that Dick decided. Slipping from behind the tapestry, he stood ready in the doorway of the chamber, with a warning hand upraised. Lawless, flushed crimson, with his eyes injected, vacillating on his feet, drew still unsteadily nearer. At last he hazily caught sight of his commander, and, in despite of Dick’s imperious signals, hailed him instantly and loudly by his name.

Dick leaped upon and shook the drunkard furiously.

“Beast!” he hissed—“beast and no man! It is worse than treachery to be so witless. We may all be shent for thy sotting.”

But Lawless only laughed and staggered, and tried to clap young Shelton on the back.

And just then Dick’s quick ear caught a rapid brushing in the arras. He leaped towards the sound, and the next moment a piece of the wall-hanging had been torn down, and Dick and the spy were sprawling together in its folds. Over and over they rolled, grappling for each other’s throat, and still baffled by the arras, and still silent in their deadly fury. But Dick was by much the stronger, and soon the spy lay prostrate under his knee, and, with a single stroke of the long poniard, ceased to breathe.

CHAPTER III THE DEAD SPYThroughout this furious and rapid passage, Lawless had looked on helplessly, and even when all was over, and Dick, already re-arisen to his feet, was listening with the most passionate attention to the distant bustle in the lower storeys of the house, the old outlaw was still wavering on his legs like a shrub in a breeze of wind, and still stupidly staring on the face of the dead man.

“It is well,” said Dick, at length; “they have not heard us, praise the saints! But, now, what shall I do with this poor spy? At least, I will take my tassel from his wallet.”

So saying, Dick opened the wallet; within he found a few pieces of money, the tassel, and a letter addressed to Lord Wensleydale, and sealed with my Lord Shoreby’s seal. The name awoke Dick’s recollection; and he instantly broke the wax and read the contents of the letter. It was short, but, to Dick’s delight, it gave evident proof that Lord Shoreby was treacherously corresponding with the House of York.

The young fellow usually carried his ink-horn and implements about him, and so now, bending a knee beside the body of the dead spy, he was able to write these words upon a corner of the paper:

My Lord of Shoreby, ye that writt the letter, wot ye why your man is ded? But let me rede you, marry not.

Jon Amend-all.

He laid this paper on the breast of the corpse; and the Lawless, who had been looking on upon these last manœuvres with some flickering returns of intelligence, suddenly drew a black arrow from below his robe, and therewith pinned the paper in its place. The sight of this disrespect, or, as it almost seemed, cruelty to the dead, drew a cry of horror from young Shelton; but the old outlaw only laughed.

“Nay, I will have the credit for mine order,” he hiccupped. “My jolly boys must have the credit on’t—the credit, brother”; and then, shutting his eyes tight and opening his mouth like a precentor, he began to thunder, in a formidable voice:

“Peace, sot!” cried Dick, and thrust him hard against the wall. “In two words—if so be that such a man can understand me who hath more wine than wit in him—in two words, and, a-Mary’s name, begone out of this house, where, if ye continue to abide, ye will not only hang yourself, but me also! Faith, then, up foot! be yare, or, by the mass, I may forget that I am in some sort your captain and in some your debtor! Go!”

The sham monk was now, in some degree, recovering the use of his intelligence; and the ring in Dick’s voice, and the glitter in Dick’s eye, stamped home the meaning of his words.

“By the mass,” cried Lawless, “an I be not wanted, I can go”; and he turned tipsily along the corridor and proceeded to flounder down-stairs, lurching against the wall.

So soon as he was out of sight, Dick returned to his hiding-place, resolutely fixed to see the matter out. Wisdom, indeed, moved him to be gone; but love and curiosity were stronger.

Time passed slowly for the young man, bolt upright behind the arras. The fire in the room began to die down, and the lamp to burn low and to smoke. And still there was no word of the return of any one to these upper quarters of the house; still the faint hum and clatter of the supper party sounded from far below; and still, under the thick fall of the snow, Shoreby town lay silent upon every side.

At length, however, feet and voices began to draw near upon the stair; and presently after several of Sir Daniel’s guests arrived upon the landing, and, turning down the corridor, beheld the torn arras and the body of the spy.

Some ran forward and some back, and all together began to cry aloud.

At the sound of their cries, guests, men-at-arms, ladies, servants, and, in a word, all the inhabitants of that great house, came flying from every direction, and began to join their voices to the tumult.

Soon a way was cleared, and Sir Daniel came forth in person, followed by the bridegroom of the morrow, my Lord Shoreby.

“My lord,” said Sir Daniel, “have I not told you of this knave Black Arrow? To the proof, behold it! There it stands, and, by the rood, my gossip, in a man of yours, or one that stole your colours!”

“In good sooth, it was a man of mine,” replied Lord Shoreby, hanging back. “I would I had more such. He was keen as a beagle and secret as a mole.”

“Ay, gossip, truly?” asked Sir Daniel, keenly. “And what came he smelling up so many stairs in my poor mansion? But he will smell no more.”

“An’t please you, Sir Daniel,” said one, “here is a paper written upon with some matter, pinned upon his breast.”

“Give it me, arrow and all,” said the knight. And when he had taken into his hand the shaft, he continued for some time to gaze upon it in a sullen musing. “Ay,” he said, addressing Lord Shoreby, “here is a hate that followeth hard and close upon my heels. This black stick, or its just likeness, shall yet bring me down. And, gossip, suffer a plain knight to counsel you; and if these hounds begin to wind you, flee! ’Tis like a sickness—it still hangeth, hangeth upon the limbs. But let us see what they have written. It is as

Comments (0)