The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗». Author Jules Verne

“Very well, we will visit it,” said Pencroff.

“We?”

“Yes, sir; We will build a decked boat, and I will undertake to steer her. How far are we from this Tabor Island?”

“A hundred and fifty miles to the northeast.”

“Is that all?” responded Pencroff.

“Why in forty-eight hours, with a good breeze, we will be there!”

“But what would be the use?” asked the reporter.

“We cannot tell till we see it!”

And upon this response it was decided that a boat should be built so that it might be launched by about the next October, on the return of good weather.

CHAPTER XXXII.

SHIP BUILDING—THE SECOND HARVEST—AI HUNTING—A NEW PLANT—A WHALE—THE HARPOON FROM THE VINEYARD—CUTTING UP THIS CETACEA—USE OF THE WHALEBONE—THE END OF MAY—PENCROFF IS CONTENT.

When Pencroff was possessed of an idea, he would not rest till it was executed. Now, he wanted to visit Tabor Island, and as a boat of some size was necessary, therefore the boat must be built. He and the engineer accordingly determined upon the following model:—

The boat was to measure thirty-five feet on the keel by nine feet beam—with the lines of a racer—and to draw six feet of water, which would be sufficient to prevent her making leeway. She was to be flush-decked, with the two hatchways into two holds separated by a partition, and sloop-rigged with mainsail, topsail, jib, storm-jib and brigantine, a rig easily handled, manageable in a squall, and excellent for lying close in the wind. Her hull was to be constructed of planks, edge to edge, that is, not overlapping, and her timbers would be bent by steam after the planking had been adjusted to a false frame.

On the question of wood, whether to use elm or deal, they decided on the latter as being easier to work, and supporting immersion in water the better.

These details having been arranged, it was decided that, as the fine weather would not return before six months, Smith and Pencroff should do this work alone. Spilett and Herbert were to continue hunting, and Neb and his assistant, Master Jup, were to attend to the domestic cares as usual.

At once trees were selected and cut down and sawed into planks, and a week later a ship-yard was made in the hollow between Granite House and the Cliff, and a keel thirty-five feet long, with stern-post and stem lay upon the sand.

Smith had not entered blindly upon this undertaking. He understood marine construction as he did almost everything else, and he had first drawn the model on paper. Moreover, he was well aided by Pencroff, who had worked as a ship-carpenter. It was, therefore, only after deep thought and careful calculation that the false frame was raised on the keel.

Pencroff was very anxious to begin the new enterprise, and but one thing took him away, and then only for a day, from the work. This was the second harvest, which was made on the 15th of April. It resulted as before, and yielded the proportion of grains calculated.

“Five bushels, Mr. Smith,” said Pencroff, after having scrupulously measured these riches.

“Five bushels,” answered the engineer, “or 650,000 grains of corn.”

“Well, we will sow them all this time, excepting a small reserve.”

“Yes, and if the next harvest is proportional to this we will have 4,000 bushels.”

“And we will eat bread.”

“We will, indeed.”

“But we must build a mill?”

“We will build one.”

The third field of corn, though incomparably larger than the others, was prepared with great care and received the precious seed. Then Pencroff returned to his work.

In the meantime, Spilett and Herbert hunted in the neighborhood, or with their guns loaded with ball, adventured into the unexplored depths of the Far West. It was an inextricable tangle of great trees growing close together. The exploration of those thick masses was very difficult and the engineer never undertook it without taking with him the pocket compass, as the sun was rarely visible through the leaves. Naturally, game was not plenty in these thick undergrowths, but three ai were shot during the last fortnight in April, and their skins were taken to Granite House, where they received a sort of tanning with sulfuric acid.

On the 30th of April, a discovery, valuable for another reason, was made by Spilett. The two hunters were deep in the south-western part of the Far West when the reporter, walking some fifty paces ahead of his companion, came to a sort of glade, and was surprised to perceive an odor proceeding from certain straight stemmed plants, cylindrical and branching, and bearing bunches of flowers and tiny seeds. The reporter broke off some of these stems, and, returning to the lad, asked him if he knew what they were.

“Where did you find this plant?” asked Herbert.

“Over there in the glade; there is plenty of it.”

“Well, this is a discovery that gives you Pencroff’s everlasting gratitude.”

“Is it tobacco?”

“Yes, and if it is not first quality it is all the same, tobacco.”

“Good Pencroff, how happy he’ll be. But he cannot smoke all. He’ll have to leave some for us.”

“I’ll tell you what, sir. Let us say nothing to Pencroff until the tobacco has been prepared, and then some fine day we will hand him a pipe full.”

“And you may be sure, Herbert, that on that day the good fellow will want nothing else in the world.”

The two smuggled a good supply of the plant into Granite House with as much precaution as if Pencroff had been the strictest of custom house officers. Smith and Neb were let into the secret, but Pencroff never suspected any thing during the two months it took to prepare the leaves, as he was occupied all day at the ship-yard.

On the 1st of May the sailor was again interrupted at his favorite work by a fishing adventure, in which all the colonists took part.

For some days they had noticed an enormous animal swimming in the sea some two or three miles distant from the shore. It was a huge whale, apparently belonging to the species australis, called “cape whales.”

“How lucky for us if we could capture it!” cried the sailor. “Oh, if we only had a suitable boat and a harpoon ready, so that I could say:—Let’s go for him! For he’s worth all the trouble he’ll give us!”

“Well, Pencroff, I should like to see you manage a harpoon. It must be interesting.”

“Interesting and somewhat dangerous,” said the engineer, “but since we have not the means to attack this animal, it is useless to think about him.”

“I am astonished to see a whale in such comparatively high latitude.”

“Why, Mr. Spilett, we are in that very part of the Pacific which whalers call the ‘whale-field,’ and just here whales are found in the greatest number.”

“That is so,” said Pencroff, “and I wonder we have not seen one before, but it don’t matter much since we cannot go to it.”

And the sailor turned with a sigh to his work, as all sailors are fishermen; and if the sport is proportionate to the size of the game, one can imagine what a whaler must feel in the presence of a whale. But, aside from the sport, such spoil would have been very acceptable to the colony, as the oil, the fat, and the fins could be turned to various uses.

It appeared as if the animal did not wish to leave these waters. He kept swimming about in Union Bay for two days, now approaching the shore, when his black body could be seen perfectly, and again darting through the water or spouting vapor to a vast height in the air. Its presence continually engaged the thoughts of the colonists, and Pencroff was like a child longing for some forbidden object.

Fortune, however, did for the colonists what they could not have done for themselves, and on the 3d of May, Neb looking from his kitchen shouted that the whale was aground on the island.

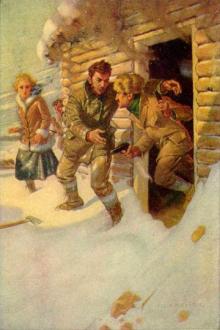

Herbert and Spilett, who were about starting on a hunt, laid aside their guns, Pencroff dropped his hatchet, and Smith and Neb, joining their companions, hurried down to the shore. It had grounded on Jetsam Point at high water, and it was not likely that the monster would be able to get off easily; but they must hasten in order to cut off its retreat if necessary. So seizing some picks and spears they ran across the bridge, down the Mercy and along the shore, and in less than twenty minutes the party were beside the huge animal, above whom myriads of birds were already hovering.

“What a monster!” exclaimed Neb.

And the term was proper, as it was one of the largest of the southern whales, measuring forty-five feet in length and weighing not less than 150,000 pounds.

Meantime the animal, although the tide was still high, made no effort to get off the shore, and the reason for this was explained later when at low water the colonists walked around its body.

It was dead, and a harpoon protruded from its left flank.

“Are there whalers in our neighborhood?” asked Spilett.

“Why do you ask?”

“Since the harpoon is still there—”

“Oh that proves nothing, sir,” said Pencroff. “Whales sometimes go thousands of miles with a harpoon in them, and I should not be surprised if this one which came to die here had been struck in the North Atlantic.”

“Nevertheless”—began Spilett, not satisfied with Pencroff’s affirmation.

“It is perfectly possible,” responded the engineer, “but let us look at the harpoon. Probably it will have the name of the ship on it.”

Pencroff drew out the harpoon, and read this inscription:—

Maria-Stella Vineyard.

“A ship from the Vineyard! A ship of my country!” be cried. “The Maria-Stella! a good whaler! and I know her well! Oh, my friends, a ship from the Vineyard! A whaler from the Vineyard!”

And the sailor, brandishing the harpoon, continued to repeat that name dear to his heart, the name of his birthplace.

But as they could not wait for the Maria-Stella to come and reclaim their prize, the colonists resolved to cut it up before decomposition set in. The birds of prey were already anxious to become possessors of the spoil, and it was necessary to drive them away with gunshots.

The whale was a female, and her udders furnished a great quantity of milk, which, according to Dieffenbach, resembles in taste, color, and density, the milk of cows.

As Pencroff had served on a whaler he was able to direct the disagreeable work of cutting up the animal—an operation which lasted during three days. The blubber, cut in strips two feet and a half thick and divided into pieces weighing a thousand pounds each, was melted down in large earthen vats, which had been brought on to the ground. And such was its abundance, that notwithstanding a third of its weight was lost by melting, the tongue alone yielded 6,000 pounds of oil. The colonists were therefore supplied with an abundant supply of stearine and glycerine, and there was, besides, the whalebone, which would find its use, although there were neither umbrellas nor corsets in Granite House.

The operation ended, to the great satisfaction of the colonists, the rest of the animal was left to the birds, who made away with it to the last vestiges, and the daily routine of work was resumed. Still, before going to the ship-yard, Smith worked on certain affairs which excited the curiosity of his companions. He took a dozen of the plates of baleen (the solid whalebone), which he cut into six equal lengths, sharpened at the ends.

“And what is that for?” asked Herbert, when they were finished.

“To kill foxes, wolves, and jaguars,” answered the engineer.

“Now?”

“No, but this winter, when we have the ice.”

“I don’t understand,” answered Herbert.

“You shall understand, my lad,” answered the engineer. “This is not my invention; it is frequently employed by the inhabitants of the Aleutian islands. These whalebones which you see, when the weather is freezing I will bend round and freeze in that position with a coating of ice; then having covered them with a bit of fat, I will place them in

Comments (0)