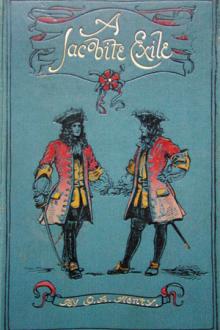

A Jacobite Exile - G. A. Henty (free reads TXT) 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

- Performer: -

Book online «A Jacobite Exile - G. A. Henty (free reads TXT) 📗». Author G. A. Henty

"No. It is four years since we met, and I have so greatly changed, in that time, that I have no fear he would recognize me. At any rate, not here in London, which is the last place he would suspect me of being in."

"That is better. Well, sir, if that be your object, I will do my best to help you. What is the fellow's name and description?"

"He called himself Nicholson, when we last met; but like enough that is not his real name, and if it is, he may be known by another here. He is a lanky knave, of middle height; but more than that, except that he has a shifty look about his eyes, I cannot tell you."

"And his condition, you say, is changeable?"

"Very much so, I should say. I should fancy that, when in funds, he would frequent places where he could prey on careless young fellows from the country, like myself. When his pockets are empty, I should say he would herd with the lowest rascals."

"Well, sir, as you say he is in funds at present, we will this evening visit a tavern or two, frequented by young blades, some of whom have more money than wit; and by men who live by their wits and nothing else. But you must not be disappointed, if the search prove a long one before you run your hare down, for the indications you have given me are very doubtful. He may be living in Alsatia, hard by the Temple, which, though not so bad as it used to be, is still an abode of dangerous rogues. But more likely you may meet him at the taverns in Westminster, or near Whitehall; for, if he has means to dress himself bravely, it is there he will most readily pick up gulls.

"I will, with your permission, take you to the better sort to begin with, and then, when you have got more accustomed to the ways of these places, you can go to those a step lower, where, I should think, he is more likely to be found; for such fellows spend their money freely, when they get it, and unless they manage to fleece some young lamb from the country, they soon find themselves unable to keep pace with the society of places where play runs high, and men call for their bottles freely. Besides, in such places, when they become unable to spend money freely, they soon get the cold shoulder from the host, who cares not to see the money that should be spent on feasting and wine diverted into the pockets of others.

"I shall leave you at the door of these places. I am too well known to enter. I put my hand on the shoulder of too many men, during the year, for me to go into any society without the risk of someone knowing me again."

They accordingly made their way down to Westminster, and Charlie visited several taverns. At each he called for wine, and was speedily accosted by one or more men, who perceived that he was a stranger, and scented booty. He stated freely that he had just come up to town, and intended to stay some short time there. He allowed himself to be persuaded to enter the room where play was going on, but declined to join, saying that, as yet, he was ignorant of the ways of town, and must see a little more of them before he ventured his money, but that, when he felt more at home, he should be ready enough to join in a game of dice or cards, being considered a good hand at both.

After staying at each place about half an hour, he made his way out, getting rid of his would-be friends with some little difficulty, and with a promise that he would come again, ere long.

For six days he continued his inquiries, going out every evening with his guide, and taking his meals, for the most part, at one or other of the taverns, in hopes that he might happen upon the man of whom he was in search. At the end of that time, he had a great surprise. As he entered the hotel to take supper, the waiter said to him:

"There is a gentleman who has been asking for you, in the public room. He arrived an hour ago, and has hired a chamber."

"Asking for me?" Charlie repeated in astonishment. "You must be mistaken."

"Not at all, sir. He asked for Mr. Charles Conway, and that is the name you wrote down in the hotel book, when you came."

"That must be me, sure enough, but who can be asking for me I cannot imagine. However, I shall soon know."

And, in a state of utter bewilderment as to who could have learnt his name and address, he went into the coffee room. There happened, at the moment, to be but one person there, and as he rose and turned towards him, Charlie exclaimed in astonishment and delight:

"Why, Harry, what on earth brings you here? I am glad to see you, indeed, but you are the last person in the world I should have thought of meeting here in London."

"You thought I was in a hut, made as wind tight as possible, before the cold set in, in earnest. So I should have been, with six months of a dull life before me, if it had not been for Sir Marmaduke's letter. Directly my father read it through to me he said:

"'Get your valises packed at once, Harry. I will go to the colonel and get your leave granted. Charlie may have to go into all sorts of dens, in search of this scoundrel, and it is better to have two swords than one in such places. Besides, as you know the fellow's face you can aid in the search, and are as likely to run against him as he is. His discovery is as important to us as it is to him, and it may be the duke will be more disposed to interest himself, when he sees the son of his old friend, than upon the strength of a letter only.'

"You may imagine I did not lose much time. But I did not start, after all, until the next morning, for when the colonel talked it over with my father, he said:

"'Let Harry wait till tomorrow. I shall be seeing the king this evening. He is always interested in adventure, and I will tell him the whole story, and ask him to write a few lines, saying that Harry and Carstairs are young officers who have borne themselves bravely, and to his satisfaction. It may help with the duke, and will show, at any rate, that you have both been out here, and not intriguing at Saint Germains.'

"The colonel came in, late in the evening, with a paper, which the king had told Count Piper to write and sign, and had himself put his signature to it. I have got it sewn up in my doublet, with my father's letter to Marlborough. They are too precious to lose, but I can tell you what it is, word for word:

"'By order of King Charles the Twelfth of Sweden. This is to testify, to all whom it may concern, that Captain Charles Carstairs, and Captain Harry Jervoise--'"

"Oh, I am glad, Harry!" Charlie interrupted. "It was horrid that I should have been a captain, for the last year, and you a lieutenant. I am glad, indeed."

"Yes, it is grand, isn't it, and very good of the king to do it like that. Now, I will go on--

"'Have both served me well and faithfully during the war, showing great valour, and proving themselves to be brave and honourable gentlemen, as may be seen, indeed, from the rank that they, though young in years, have both attained, and which is due solely to their deserts.'

"What do you think of that?"

"Nothing could be better, Harry. Did you see my father at Gottenburg?"

"Yes. The ship I sailed by went to Stockholm, and I was lucky enough to find there another, starting for England in a few hours. She touched at Gottenburg to take in some cargo, and I had time to see Sir Marmaduke, who was good enough to express himself as greatly pleased that I was coming over to join you."

"Well, Harry, I am glad, indeed. Before we talk, let us go in and have supper, that is, if you have not already had yours. If you have, I can wait a bit."

"No; they told me you had ordered your supper at six, so I told them I would take mine at the same time; and, indeed, I can tell you that I am ready for it."

After the meal, Charlie told his friend the steps he was taking to discover Nicholson.

"Do you feel sure that you would know him again, Harry?"

"Quite sure. Why, I saw him dozens of times at Lynnwood."

"Then we shall now be able to hunt for him separately, Harry. Going to two or three places, of an evening, I always fear that he may come in after I have gone away. Now one of us can wait till the hour for closing, while the other goes elsewhere."

For another fortnight, they frequented all the places where they thought Nicholson would be most likely to show himself; then, after a consultation with their guide, they agreed that they must look for him at lower places.

"Like enough," the tipstaff said, "he may have run through his money the first night or two after coming up to town. That is the way with these fellows. As long as they have money they gamble. When they have none, they cheat or turn to other evil courses. Now that there are two of you together, there is less danger in going to such places; for, though these rascals may be ready to pick a quarrel with a single man, they know that it is a dangerous game to play with two, who look perfectly capable of defending themselves."

For a month, they frequented low taverns. They dressed themselves plainly now, and assumed the character of young fellows who had come up to town, and had fallen into bad company, and lost what little money they had brought with them, and were now ready for any desperate enterprise. Still, no success attended their search.

"I can do no more for you," their guide said. "I have taken you to every house that such a man would be likely to use. Of course, there are many houses near the river frequented by bad characters. But here you would chiefly meet men connected, in some way, with the sea, and you would be hardly likely to find your man there."

"We shall keep on searching," Charlie said. "He may have gone out of town for some reason, and may return any day. We shall not give it up till spring."

"Well, at any rate, sirs, I will take your money no longer. You know your way thoroughly about now, and, if at any time you should want me, you know where to find me. It might be worth your while to pay a visit to Islington, or even to go as far as Barnet. The fellow may have done something, and may think it safer to keep in hiding, and in that case Islington and Barnet are as likely to suit him as anywhere."

The young men had, some time before, left the inn and taken a lodging. This they found much cheaper, and, as they were away from breakfast until midnight, it mattered little where they slept. They took the advice of their guide, stayed a couple of nights at Islington, and then went to Barnet. In these places there was no occasion to visit the taverns, as, being comparatively small, they would, either in the daytime or after dark, have

Comments (0)