The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗». Author Jules Verne

“What magnificent flames!” cried Herbert, as a sheaf of fire shot up, unobscured by the vapors, from the crater. From its midst luminous fragments and bright scintillations were thrown in every direction. Some of them pierced the dome of smoke, leaving behind them a perfect cloud of incandescent dust. This outpouring was accompanied by rapid detonations like the discharge of a battery of mitrailleuses.

Smith, the reporter, and the lad, after having passed an hour on Prospect Plateau, returned to Granite House. The engineer was pensive, and so much preoccupied that Spilett asked him if he anticipated any near danger.

“Yes and no,” responded Smith.

“But the worst that could happen,” said the reporter, “would be an earthquake, which would overthrow the island. And I don’t think that is to be feared, since the vapors and lava have a free passage of escape.”

“I do not fear an earthquake,” answered Smith, “of the ordinary kind, such as are brought about by the expansion of subterranean vapors. But other causes may bring about great disaster.”

“For example?”

“I do not know exactly—I must see—I must visit the mountain. In a few days I shall have made up my mind.”

Spilett asked no further questions, and soon, notwithstanding the increased violence of the volcano, the inhabitants of Granite House slept soundly.

Three days passed, the 4th 5th, and 6th of January, during which they worked on the ship, and, without explaining himself further, the engineer hastened the work as much as possible. Mount Franklin was covered with a sinister cloud, and with the flames vomited forth incandescent rocks, some of which fell back into the crater. This made Pencroff, who wished to look upon the phenomenon from an amusing side, say—

“Look! The giant plays at cup and ball! He is a juggler.”

And, indeed, the matters vomited forth fell back into the abyss, and it seemed as if the lavas, swollen by the interior pressure, had not yet risen to the mouth of the crater. At least, the fracture on the northeast, which was partly visible, did not pour forth any torrent on the western side of the mountain.

Meanwhile, however pressing the ship-building, other cares required the attention of the colonists in different parts of the island. First of all, they must go to the corral, where the moufflons and goats were enclosed, and renew the provisions for these animals. It was, therefore, agreed that Ayrton should go there the next day, and, as it was customary for but one to do this work, the others were surprised to hear the engineer say to Ayrton:——

“As you are going to the corral to-morrow, I will go with you.”

“Oh! Mr. Smith!” cried the sailor, “our time is very limited, and, if you go off in this way, we lose just that much help!”

“We will return the next day,” answered Smith, “but I must go to the corral—I wish to see about this eruption.”

“Eruption! Eruption!” answered Pencroff, with a dissatisfied air. “What is there important about this eruption? It don’t bother me!”

Notwithstanding the sailor’s protest, the exploration was decided upon for the next day. Herbert wanted to go with Smith, but he did not wish to annoy Pencroff by absenting himself. So, early the next morning, Smith and Ayrton started off with the wagon and onagers.

Over the forest hung huge clouds constantly supplied from Mount Franklin with fuliginous matter. They were evidently composed of heterogeneous substances. It was not altogether the smoke from the volcano that made them so heavy and opaque. Scoriæ in a state of powder, pulverized puzzolan and grey cinder as fine as the finest fecula, were held in suspension in their thick folds. These cinders remain in air, sometimes, for months at a time. After the eruption of 1783, in Iceland, for more than a year the atmosphere was so charged with volcanic powder that the sun’s rays were scarcely visible.

Usually, however, these pulverized matters fall to the earth at once, and it was so in this instance. Smith and Ayrton had hardly reached the corral, when a sort of black cloud, like fine gunpowder, fell, and instantly modified the whole aspect of the ground. Trees, fields, everything was covered with a coating several fingers deep. But, most fortunately, the wind was from the northeast, and the greater part of the cloud was carried off to sea.

“That is very curious,” said Ayrton.

“It is very serious,” answered Smith. This puzzolan, this pulverized pumice stone, all this mineral dust in short, shows how deep-seated is the commotion in the volcano.

“But there is nothing to be done.”

“Nothing, but to observe the progress of the phenomenon. Employ yourself, Ayrton, at the corral, and meanwhile I will go up to the sources of Red Creek and examine the state of the mountain on its western side. Then——”

“Then, sir?”

“Then we will make a visit to Crypt Dakkar—I wish to see—Well, I will come back for you in a couple of hours.”

Ayrton went into the corral, and while waiting for the return of the engineer occupied himself with the moufflons and goats, which showed a certain uneasiness before these first symptoms of an eruption.

Meantime Smith had ventured to climb the eastern spurs of the mountain, and he arrived at the place where his companions had discovered the sulphur spring on their first exploration.

How everything was changed! Instead of a single column of smoke, he counted thirteen escaping from the ground as if thrust upward by a piston. It was evident that the crust of earth was subjected in this place to a frightful pressure. The atmosphere was saturated with gases and aqueous vapors. Smith felt the volcanic tufa, the pulverulent cinders hardened by time, trembling beneath him, but he did not yet see any traces of fresh lava.

It was the same with the western slope of the mountain. Smoke and flames escaped from the crater; a hail of scoriæ fell upon the soil; but no lava flowed from the gullet of the crater, which was another proof that the volcanic matter had not attained the upper orifice of the central chimney.

“And I would be better satisfied if they had!” said Smith to himself. “At least I would be certain that the lavas had taken their accustomed route. Who knows if they may not burst forth from some new mouth? But that is not the danger! Captain Nemo has well foreseen it! No! the danger is not there!”

Smith went forward as far as the enormous causeway, whose prolongation enframed Shark Gulf. Here he was able to examine the ancient lava marks. There could be no doubt that the last eruption had been at a far distant epoch.

Then he returned, listening to the subterranean rumblings, which sounded like continuous thunder, and by 9 o’clock he was at the corral.

Ayrton was waiting for him.

“The animals are attended to, sir,” said he.

“All right, Ayrton.”

“They seem to be restless, Mr. Smith.”

“Yes, it is their instinct, which does not mislead them.”

“When you are ready—”

“Take a lantern and tinder, Ayrton, and let us go.”

Ayrton did as he was told. The onagers had been unharnessed and placed in the corral, and Smith, leading, took the route to the coast.

They walked over a soil covered with the pulverulent matter which had fallen from the clouds. No animal appeared. Even the birds had flown away. Sometimes a breeze passed laden with cinders, and the two colonists, caught in the cloud, were unable to see. They had to place handkerchiefs over their eyes and nostrils or they would have been blinded and suffocated.

Under these circumstances they could not march rapidly. The air was heavy, as if all the oxygen had been burned out of it, making it unfit to breathe. Every now and then they had to stop, and it was after 10 o’clock when the engineer and his companion reached the summit of the enormous heap of basaltic and porphyrytic rocks which formed the northwest coast of the island.

They began to go down this abrupt descent, following the detestable road, which, during that stormy night had led them to Crypt Dakkar. By daylight this descent was less perilous, and, moreover, the covering of cinders gave a firmer foothold to the slippery rocks.

The projection was soon attained, and, as the tide was low, Smith and Ayrton found the opening to the crypt without any difficulty.

“Is the boat there?” asked the engineer.

“Yes, sir,” answered Ayrton, drawing the boat towards him.

“Let us get in, then, Ayrton,” said the engineer.

The two embarked in the boat. Ayrton lit the lantern, and, placing it in the bow of the boat, took the oars, and Smith, taking the tiller, steered into the darkness.

The Nautilus was no longer here to illuminate this sombre cavern. Perhaps the electric irradiation still shone under the waters, but no light came from the abyss where Captain Nemo reposed.

The light of the lantern was barely sufficient to permit the engineer to advance, following the right hand wall of the crypt. A sepulchral silence reigned in this portion of the vault, but soon Smith heard distinctly the mutterings which came from the interior of the earth.

“It is the volcano,” he said.

Soon, with this noise, the chemical combinations betrayed themselves by a strong odor, and sulphurous vapors choked the engineer and his companion.

“It is as Captain Nemo feared,” murmured Smith, growing pale. “We must go on to the end.”

Twenty-five minutes after having left the opening the two reached the terminal wall and stopped.

Smith standing on the seat, moved the lantern about over this wall, which separated the crypt from the central chimney of the volcano. How thick was it? Whether 100 feet or but 10 could not be determined. But the subterranean noises were too plainly heard for it to be very thick.

The engineer, after having explored the wall along a horizontal line, fixed the lantern to the end of an oar and went over it again at a greater height.

There, through scarcely visible cracks, came a pungent smoke, which infected the air of the cavern. The wall was striped with these fractures, and some of the larger ones came to within a few feet of the water.

At first, Smith rested thoughtful. Then he murmured these words:—

“Yes! Captain Nemo was right! There is the danger, and it is terrible!”

Ayrton said nothing, but, on a sign from the engineer, he took up the oars, and, a half hour later, he and Smith came out of Crypt Dakkar.

CHAPTER LXI

SMITH’S RECITAL—HASTENING THE WORK—A LAST VISIT TO THE CORRAL—THE COMBAT BETWEEN THE FIRE AND THE WATER—THE ASPECT OF THE ISLAND—THEY DECIDE TO LAUNCH THE SHIP—THE NIGHT OF THE 8TH OF MARCH.

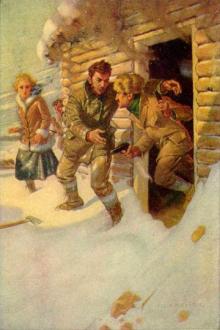

The next morning, the 8th of January, after a day and night passed at the corral, Smith and Ayrton returned to Granite House.

Then the engineer assembled his companions, and told them that Lincoln Island was in fearful danger—a danger which no human power could prevent.

“My friends,” said he,—and his voice betrayed great emotion,—“Lincoln Island is doomed to destruction sooner or later; the cause is in itself and there is no means of removing it!”

The colonists looked at each other. They did not understand him.

“Explain yourself, Cyrus,” said Spilett.

“I will, or rather I will give you the explanation which Captain Nemo gave me, when I was alone with him.”

“Captain Nemo!” cried the colonists.

“Yes; it was the last service he rendered us before he died.”

“The last service!” cried Pencroff. “The last service! You think, because he is dead, that he will help us no more!”

“What did he say?” asked the reporter.

“This, my friends,” answered the engineer. “Lincoln Island is not like the other islands of the Pacific, and a particular event, made known to me by Captain Nemo, will cause, sooner or later, the destruction of its submarine framework.”

“Destruction of Lincoln Island! What an idea!”

Comments (0)