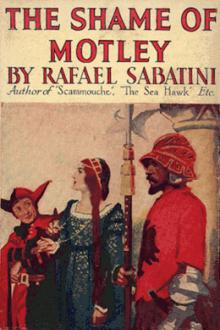

The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

He looked about him like a man whose wits have been scattered suddenly to the four winds of Heaven.

“But this litter,” he mumbled, riveting his dazed eyes upon me, “and these four knaves—?”

“Tell me,” I questioned, with sudden earnestness, “are you in quest of just such a party?”

“Aye that I am,” he answered sharply, intelligence returning to his glance, inquiry burning in it.

“And would the men, peradventure, be wearing the livery of the House of Santafior?”

His quick assent came almost choked in a company of oaths.

“Why then, if that be your quarry, you are but wasting time. Such a party passed us at the gallop about an hour ago. It would be an hour, would it not, Giacopo?”

“I should say an hour,” answered the lacquey dully.

“In what direction?” came Ramiro’s frenzied question. He doubted me no longer.

“In the direction of Fabriano I should say,” I answered. “Although it may well be that they were making for Sinigaglia. The road branches farther on.”

He waited for no more. Without word of thanks for the priceless information I had given him, he wheeled his horse, and shouted a hoarse command to his followers. A moment later and they were cantering past us, the snow flying beneath their hoofs; within five minutes the last of them had vanished round an angle of the road, and the only indication of the halt they had made was the broad path of dirty brown where their horses had crushed the snow.

I have been an actor in few more entertaining comedies than the cozening of Ser Ramiro, and a witness of nothing that afforded me at once so much relief and relish as his abrupt departure. I sank back on the cushions of my litter, and gave myself over to a burst of full-souled laughter which was interrupted ere it was half done by Giacopo, who had dismounted and approached me.

“You have fooled us finely,” said he, with venom.

I quenched my laughter to regard him. Of what did he babble? Was he, and were his fellows, too, so ungrateful as to bear a grudge against the man who had saved them?

“You have fooled us finely,” he insisted in a louder voice.

“That, knave, is my trade,” said I. “But it rather seems to me that it was Messer Ramiro del’ Orca whom I fooled.”

“Aye,” he answered querulously. “But what when he discerns how you have played upon him? What when he discovers the trick by which you have thrown him off the scent? What when he returns?”

“Spare me” I begged, “I am but indifferently skilful at conjecture.”

“Nay, but you shall answer me,” he cried, livid with a passion that my bantering tone had quickened.

“Can it be that you are indeed curious to know what will befall when he returns?” I questioned meekly.

“I am,” he snorted, with an angry twist of the lips.

“It should be easy to gratify the morbid spirit of curiosity that actuates you. Remain here, and await his return. Thus shall you learn.”

“That will not I,” he vowed.

“Nor I, nor I, nor I!” chorused his followers.

“Then, why plague me with unprofitable questions? What concern is it of ours how Messer del’ Orca shall vent his wrath when he is disillusioned. Your duty now is to rejoin your mistress. Ride hard for Cagli. Seek her at the sign of ‘The Full Moon,’ and then away for Pesaro. If you are brisk you will gain the shelter of the Lord Giovanni Sforza’s fortress long before Messer del’ Orca again picks up the scent, if, indeed, he ever does so.”

Giacopo laughed derisively till his fat body shook with the scornful mirth of him.

“By my faith, I’m done with the business,” he cried, and the other three expressed a very hearty agreement with that attitude.

“How done with it?” I asked.

“I shall make my way back across the hills and so retrace my steps to Rome. I’ll risk my head no more for any lady or any Fool.”

“If you should ever chance to risk it for yourself,” said I, with unmeasured scorn, “you’ll risk it for the greatest fool and the cowardliest rogue that ever shamed the name of man. And your mistress? Is she to wait at Cagli until doomsday? If anywhere within the bulk of that elephant’s body there lurks the heart of a rabbit, you’ll get you to horse and ride to the help of that poor lady.”

They resented my tone, and showed their resentment plainly. Messer Giacopo went the length of raising his hand to me. But I am a man of amazing strength—amazing inasmuch as being slender of shape I do not have the air of it. Leaping suddenly from the litter, I caught that miserable vassal by the breast of his doublet, shook him once or twice, then tossed him headlong into a drift of snow by the roadside.

At that they bared their knives and made shift to attack me. But I flung myself on to one of the mules of the litter, and showing them the stout Pistoja dagger that I carried, I presented with it a bold and truculent front, no whit intimidated by their numbers. Four to one though they were, they thought better of it. A moment they stood off, consulting among themselves; then Giacopo mounted, and with some mocking counsel as to how I should dispose of the litter and the mules, they made off, no doubt, to find their way back to Rome. Giacopo, as I was afterwards to discover, was Madonna Paola’s purse-bearer, so that they would not lack for means.

Awhile I stayed there, cursing them for the white�livered cravens that they were, and thinking of that poor child who had ridden on to Cagli, and who would await them in vain. There, on the mule, I sat in the noontide sunlight, and pondered this, so absorbed in her affairs as to have grown forgetful of my own. At last I resolved to ride on to Cagli alone, and inform her that her men were fled.

There was no time to lose, for as that rogue Giacopo had said, Ramiro del’ Orca might discover at any moment how he had been tricked, and return hot-foot to find me and extort the truth from me by such means as I had no stomach for enduring.

First, then, it was of moment thoroughly to efface our tracks, leaving no sign that might guide Meser Ramiro to repair the error into which I had tricked him. Slowly, says the proverb, one journeys far and safely. Slowly, then, did I consider! The escort was, no doubt, on its way back to Rome, and if I could but rid myself of that cumbrous litter, Ser Ramiro would find himself mightily hard put to it to again pick up the trail. I remembered a ravine a little way behind, and I rode my mule back to that as fast as it would travel with the litter and the other mule attached to it. Arrived there, I unharnessed the beasts on the very edge of that shallow precipice. Then exerting all my strength, I contrived to roll the litter over. Down that steep incline it went, over and over, gathering more snow to itself at every revolution, and sinking at last into the drift at the bottom. There were signs enough to show its presence, but those signs would hardly be read by any but the sharpest eyes, or by such as might be looking for it in precisely such a position. I must trust to luck that it escaped the notice of Messer Ramiro. But even if he did discover it, I did not think that it would tell him overmuch.

That done I resumed my hat and cloak—which I had retained—mounted once more, and urging the other mule along, I proceeded thus as fast as might be for a half-league or so in the direction of Cagli. That distance covered, again I halted. There was not a soul in sight. I stripped one of the mules of all its harness, which I buried in the snow, behind a hedge, then I drove the beast loose into a field. The peasant-owner of that land might conclude upon the morrow that it had rained asses in the night.

And now I was able to travel at a brisker pace, and in an hour or so I had passed the point where the road diverged, and I caught a glimpse of the four grooms, already high up in the hills which they were crossing. Whether they saw me or not I do not know, but with a last curse at their cowardice I put them from my mind, and cantered briskly on towards Cagli. It was a short league farther, and in little more than half an hour, my mule half-dead, I halted at the door of “The Full Moon.”

Flinging my reins to the ostler, I strode into the inn, swaddled in my cloak, and called for the hostess. The place was empty, as indeed all Cagli had seemed when I rode up. She came forward—a woman with a brown, full face, and large kindly eyes—and I asked her whether a lady had arrived there in safety that morning. At first she seemed mistrustful, but when I had assured her that I was in that lady’s service, she frankly owned that Madonna was safe in her own room. Thither I allowed her to lead me, at once eager and reluctant. Eager with my own eyes to assure myself of her perfect safety; reluctant that, since a man may not penetrate to a lady’s chamber hat on head, by uncovering I must disclose my shameful trade. Yet there was nothing for it but a bold face, and as I mounted the stairs in the woman’s wake, I told myself that I was doubly a fool to be tormented by qualms of such a nature.

Hat in hand I followed the hostess into Madonna’s room. The lady rose from the window-seat to greet me, her face pale and her gentle eyes wearing an anxious look. At sight of my head crowned with the crested, horned hood of folly, a frown of bewilderment drew her brows together, and she looked more closely to see whether I was indeed the man who had befriended her that morning in her extremity. In the eyes of the hostess I caught a gleam of recognition. She knew me for the merry loon who had entertained her guests one night a fortnight since, when on my way from Pesaro to Rome. But before she could give expression to this discovery of hers, the lady spoke.

“Leave us awhile, my woman,” she commanded. But I stayed the hostess as she was withdrawing.

“This lady,” said I, “will need an escort of three or four stout knaves upon a journey that she is going. She will be setting out as soon as may be.”

“But what of my grooms?” cried the lady.

“Madonna,” I informed her, “they have deserted you. That is the reason of my presence here. You shall hear the story of it presently. Meanwhile, we must arrange to replace them.” And I turned again to the hostess.

She was standing in thought, a doubtful expression on her face. But as I looked at her she shook her head.

“There is no such escort to be found to-day in Cagli,” she made answer. “The town is all but empty, and every lusty man is either gone on the pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loretto, or else is at Pesaro for the Feast of the Epiphany.”

It was in vain that I protested that a couple of

Comments (0)