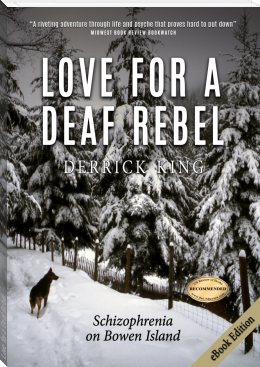

Love for a Deaf Rebel - Derrick King (top 100 novels .txt) 📗

- Author: Derrick King

- Performer: -

Book online «Love for a Deaf Rebel - Derrick King (top 100 novels .txt) 📗». Author Derrick King

I held Pearl’s hand for an hour. The doctor removed the contacts, examined her cherry-red eyes, taped patches over them, gave me a bottle of eye drops, and told me to remove her patches in the morning. For one night, Pearl was deaf-blind. I helped her to her feet, guided her to a toilet, and helped her to use it. Our journey home took more than an hour, and all while she was soaking wet. I undressed her, washed her, fed her, and put her to bed.

I changed and walked to the barn in my overalls. The horses stood outside and pawed the ground, thirsty and hungry. The doors were closed. The area around the sink was wet. A pail of whitewash stood on a ladder, and a brush lay on the floor. I looked up and saw that the ceiling around the light had been whitewashed. Pearl had been painting directly over her head without any eye protection! I cleaned up and did the chores.

In the morning, I removed her eye patches. Her eyes and eyelids were red and swollen.

“I see through a fog. I can’t go to work today.”

“You were lucky. How did you call the ambulance?”

“I stumbled to the house. My eyes were on fire. I had to feel the number-holes on the telephone dial. I dialed 911. Then I talked.” She mumbled, “Elp … ‘o-oor … ‘ole 643 … I am ‘eaf … ‘elp ….” “I hoped someone was listening. I didn’t hang up. I talked and talked. Whisky barked when they came. I held his collar and walked to the door with my eyes closed.”

The incident made us talk about future emergencies. What if she had another accident? What if the house caught fire? What if there was an intruder? I bought a Radio Shack dialer and programmed it to call the police, fire department, and ambulance by pushing one button. The cassette would play: “This is an emergency. Pearl King is calling from Trunk Road pole 643. I am deaf. I need help. This is an emergency.” We kept it in the bedroom.

In August, we ordered hay for our animals and to resell at a profit. I ordered a semi-trailer full, seven tons. A motor-escalator lifted the 150 bales into our hayloft. We built bridle racks and saddlehorses in the tack room to be ready for four horses, and a hitching post, too.

To make the saddlehorses, Pearl helped feed planks into the saw while I guided them through the blade. I milled the edges with a router while Pearl swept the chips into paper bags to burn as fuel. She pointed at the Black & Decker Workmate, a woodworking vise. “Where did you get that tool?”

“Father left it here after we made the barn doors.”

During dinner, Pearl startled me by signing, “You bought that tool.”

“It’s my father’s tool. I am borrowing it.”

“You are spending our money secretly! Admit it!”

I was astonished. “Call Father through the MRC. Ask him.”

Pearl sneered. “You lie! Your father will repeat what you said because you told him to tell me that. You lie! You lie!”

I brought the well-worn tool into the kitchen. “Look closely. Is it new?”

“You made it look like that!”

“You sound like Frank. Why are you arguing about a stupid tool?”

She glared at me. “Because you lie to me! Fuck you!” She gave me her “middle finger” the deaf way, horizontally instead of vertically.

I lost my self-control. I grabbed her shoulders and screamed, “It’s not my fucking tool!”

Pearl held out her hands to show me they trembled. “I’m shocked!” She put her hands on her face. “My face is hot. I know you wanted to hurt me. Tonight I will sleep alone,” she signed calmly.

At bedtime, Pearl calmly pulled the plastic sheets off the sofa and slept in the living room for the first time. I listened to the rain on the bedroom skylight and wondered what had happened. I was alarmed and confused. I couldn’t see a pattern in her behavior; I saw episodes, and I rationalized each one.

After weeks of repairs, the walls and ceiling were ready for repainting. I bought five recessed light fixtures for the kitchen. We needed to install them before we painted the ceiling.

“It’s a two-man job, so you need to help. You work in the attic and pull the wire to each hole. I’ll stand here and wave a light through each hole so you can find it. You push the wire to me. I’ll pull it down, and push another wire up. You pull that wire to the next hole, and push it down. Then I give you another wire, and so on to the last hole.”

“You should work in the attic because you know where the wires go.”

“But the attic over the kitchen is low. I will wreck the ceiling if I slip. This wiring should have been done before the ceiling was installed. If you need to communicate, then sign through a hole.”

Pearl put on her overalls and gardening kneepads, and she climbed the ladder in the bedroom into the attic hatch.

A few minutes later, she reached the kitchen and lowered her hand through the first hole.

“Turn off the electricity.”

That wasn’t planned, but it was difficult to reply. I shut off the circuit, and the kitchen went black. I looked up into the lamp-hole and saw her face illuminated by the utility lamp. I passed the next wire up, but Pearl didn’t take it. A few minutes later, she climbed down from the attic hatch, livid.

“You tried to kill me with electricity! I pushed the end of the wire against a metal box, and I saw sparks!”

“The power was on inside the first wire because it is connected to the kitchen, and I wanted to have light. Now the kitchen is dark. You were safe. The insulation protects you.”

“No, I tested you! What if I touched the wires inside?”

“Nothing. You were on dry wood. You were safe.”

I tried to hug her, but she pulled back. We continued the project with our locations reversed; now, I worked in the attic, banging my head on the rafters. Pearl was as calm as if she had not just had a terrified outburst, and again I assumed that was the end of it.

Alberta School for the Deaf

“We need a vacation. Alan and Rose can care for the animals,” signed Pearl.

“We do need a vacation. Where do you want to go?”

“Alberta by motorcycle. I will show you where I grew up. We haven’t ridden the motorcycle since Mexico. I love the way people stare when we climb off your big motorcycle in our leather suits, and then we surprise people by signing.”

We visited Pearl’s sisters, her brother, and a few deaf friends. Her deaf friends usually signed very swiftly, so I often spent my time speaking with their children. Most nights we saved money by sleeping in sleeping bags on our hosts’ living room floors. We visited all her aunts and uncles on her mother’s side during our years together, but we never visited any on her father’s side.

We visited her uncle’s ranch in the Rocky Mountain foothills. His dogs chased the motorcycle as we rode to a mobile home at the end of a gravel road. We dismounted beside a Dodge pickup truck; firewood, timber, a come-along, a shovel, and a bucket of wrenches lay in the back of it. Farm equipment and scraps of steel lay about. Barbed-wire fences led to the horizon.

I took off my gloves. “This property is huge!”

“Here is where I spent my summers, playing with animals and helping my uncle do chores,” signed Pearl, grinning.

The sliding door opened. A handsome, rugged man with a tanned face and a cowboy’s mustache beckoned us into his home. “I’m glad you could make it.” He hugged Pearl, and we introduced ourselves. We took off our boots and went inside. Like the rest of Pearl’s family, her uncle, Ernie, used only oral communication.

Ornate cowboy boots, worn workman’s boots, and mud-covered rubber boots stood in a row next to a boot-jack welded from horseshoes. The living room was decorated with glittering trophies and photographs of draft horses. Pearl and I took off our leathers while Ernie made coffee and tossed pieces of firewood into the stove.

I looked at his photographs. “Horses as far as the eye can see. How big is your land?”

“It’s 160 acres.”

“How many horses do you have now?” signed Pearl.

“Five hundred, plus six Belgians. I race my Belgians in the draft horse competitions in the Calgary Stampede. I do hayrides, too.”

“Five hundred! But what do you do with them all?”

“He raises and sells them,” Pearl signed.

“This is as close as you can get to Marlboro country,” he said.

Later, when Pearl was walking in a paddock, I asked Ernie where the horses came from, how much they cost, where they went, and why they seemed to be feral.

“Horses are my life. I love them more than anything. I buy them from Manitoba PMU farms and sell them to Alberta slaughterhouses. PMU stands for Pregnant Mare Urine. The farms breed mares and collect urine while they’re pregnant. It’s made into hormone pills; that’s where the brand Premarin comes from. I buy the stallions and retired mares, fatten them, and sell them for horsemeat. I could never bring myself to tell Pearl the truth.”

That evening, we listened to Ernie’s cowboy tales. Then we climbed into bunk beds in his spare room for the night.

For me, the highlight of our trip was our visit to the Alberta School for the Deaf. We walked inside dressed in full leather, carrying helmets, goggles, and gloves and looking like World War I pilots.

A woman approached. She did a double-take. “My God!—it’s Pearl!” she signed and shouted. “I didn’t think I’d ever see Pearl again.”

The women hugged and laughed. “Meet Joan, the only teacher I ever liked. She didn’t have a negative attitude like the other teachers.”

“Can we look around the school?” I signed.

“It isn’t allowed. It’s a rule here,” Joan signed and said.

“But we rode from Vancouver,” signed Pearl. “When I graduated, I had spent most of my life inside this building.”

“Then I’ll escort you. The term doesn’t start until next week, so you’re lucky.”

We walked down a corridor and peered in an open door. The room was empty but for a woman and boy. The woman wore a microphone-headset and was talking and signing. The boy listened to her through headphones. Then a bell rang, and a red light mounted over the door spun. The teacher and student left the classroom together, smiling and signing.

“That light looks like it came from a police car,” I signed.

“It did,” Joan signed and said. “Usually, there are ten students, but this is summer school.”

“I had to sit in a group wearing headphones while the teacher talked without signing,” signed Pearl, as Joan interpreted. “I couldn’t understand anything, so I didn’t learn anything except from the blackboard and books.”

“Signing wasn’t allowed. If parents chose to sign at home, that was their choice, but we told them that they were hindering their children’s language development.”

“I had to wait until the teacher wrote on the blackboard before I could learn. It was like reading a book word … by … word. It made me fall asleep! I’m not good at lipreading. Does that mean I’m not allowed to learn? Teachers hit students who signed, but we dared to sign behind the teachers’ backs to avoid going crazy in class.”

“Now we communicate every way we can. In 1964, the Babbidge Report on deaf education concluded that oral education was a failure, but it took ten years before the USA passed a mainstreaming act. Canada followed. Pearl missed it.”

“Does the new system work better?”

“There are pros and cons. It’s hard to promote reading and writing in a signing environment. In childhood, the hassle of English is reduced, but although it’s easier to learn other subjects than before, it’s harder to learn English. Few graduates reach grade nine reading because English is their second language. ASL is useless outside, so the tradeoff for using it in the classroom is further isolation of deafies and limitation of their opportunities. Limited reading spells limited thinking, and that means immaturity whether you are deaf, blind, hearing, or sighted.”

We entered a dormitory. “Look at those beds in a row. We were punished if we didn’t make our beds perfectly every day.” We went into a white-tiled

Comments (0)