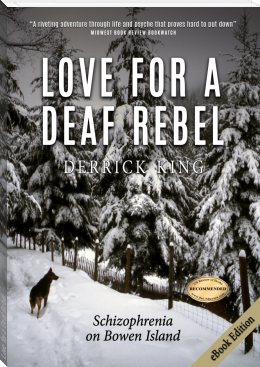

Love for a Deaf Rebel - Derrick King (top 100 novels .txt) 📗

- Author: Derrick King

- Performer: -

Book online «Love for a Deaf Rebel - Derrick King (top 100 novels .txt) 📗». Author Derrick King

“It tells a story of hikers on a mountain.”

“What about this one?” Pearl pointed at the cover of Vivaldi’s L’Amoroso Concerto. I put my arm around her, kissed her, and pointed at the cover, which had two lovers caressing in the grass.

Pearl nodded.

Pearl always wore high-neckline clothes. Her shirt had six buttons, with only one opened. I opened one more and kissed her neck. She nodded as the Moody Blues urged me on.

But you will love me tonight,

We alone will be alright,

In the end.

I pulled back, but Pearl smiled as though she were melting.

Give just a little bit more,

Take a little bit less,

From each other tonight.

Pearl’s skin became flushed as I followed her onto the carpet.

Admit what you’re feeling

And see what’s in front of you,

It’s never out of your sight.

We were lucky we did not become parents that night. Pearl started on the Pill, and every weekend became a sleepover.

When I returned from a live-aboard sailing course, I was delighted to find a stack of letters from Pearl in my mailbox. An hour later, Pearl walked over and invited me to her mother’s home for their family reunion dinner. At last, I would meet her family.

A few days later, we drove to her mother’s apartment. Pearl pushed the intercom button in the lobby. I nodded to Pearl when I heard hello from the speaker.

“Harroo,” said Pearl into the intercom.

“Come in, Pearl,” boomed the voice through the intercom, and the entrance door clicked open.

Pearl opened her mother’s unlocked door, and we walked into the aroma of home cooking. Pearl’s mother was friendly but reserved, and she looked every one of her fifty-one years. She introduced me to Art, who was her third husband, to Pearl’s siblings Kevin, Carol, and Debbie, and to Debbie’s husband; all were visiting from Alberta. Her mother made me feel welcome, yet I sensed a vague sadness about her, a feeling I had never felt before. There was warmth and love in Pearl’s family, but there was little cheer. Among her mother’s four children, only Debbie was married and had a child.

Pearl’s mother and Art had been married for three years, and it seemed as though they were still trying to fit furniture from two apartments into one. Art led me through a maze of furniture to a sofa by the window. He had been laid off as a provincial park gatekeeper, and now spent his time working part-time as the caretaker of their apartment building, woodworking, organizing Elks affairs with Pearl’s mother, and grumbling about the government. Pearl’s mother worked in catering and seemed to have an endless supply of one-gallon jars.

I sat next to Pearl, who sat opposite her mother. I couldn’t see how Pearl could think that her mother had killed her father.

“Delicious,” signed Pearl. “Good cook,” she wrote.

“Put that notepad away, Pearl,” said her mother. “Are you wearing your hearing aid?”

“Noo …,” said Pearl almost inaudibly. “Lef a hoe.”

“She left it at home,” her mother said.

“In the three months since we met, I never heard Pearl speak a sentence.”

“What?” gestured Pearl.

“Derrick never heard you talk before,” said her mother.

“Eee ill sigh soo …,” Pearl mumbled.

“He will sign soon,” her mother said. “Pearl needn’t be ashamed of her accent.”

“I signed up for an ASL course.”

“Pearl will like that,” said Carol. “It will be an adventure for both of you.”

“I once bought a book of signs,” said Debbie. “But we live in Alberta, and we can’t use sign language on the phone.”

“What?” gestured Pearl.

“Derrick will take a course,” said her mother.

“Do you know any signs?”

“None.”

“Why don’t you learn a few? It’s never too late.”

“We do just fine orally. Don’t we, Pearl?”

“What?” gestured Pearl.

“She is misbehaving because we have a visitor. Naughty girl.”

“Pearl told me she loves you, but she hardly knows you because you won’t sign,” I said.

“I follow expert advice. Everything I have done is to support Pearl to become as oral as possible so she can function in the real world. The greater her oral skills, the greater her opportunities, so the better her life will be. We want the best for her.”

“Even if you learn to sign, you must help her with lipreading and speech,” said Kevin.

“One way doesn’t rule out the other, does it?”

“It does,” said Pearl’s mother. “That’s the problem.”

“At thirty, you might as well communicate any way you can. I suppose she’s not with you enough now for your oral practice to make much of a difference.”

“Hearing signers don’t help. Why do you want to sign? To keep Pearl for yourself? Talk to her, and listen to her talk, too. Help her with the hearing world. We support deaf children through the Elks’ oral development fund.”

We ate a wonderful roast beef dinner. There was no signing or writing. An outsider would never have suspected that one of us was deaf.

I invited Pearl to ride on my motorcycle to Mount Baker for a roadhouse lunch and then to my parents’ for dinner. Pearl was happy to have a chance to meet my parents.

Eugénie’s leather suit and helmet fit Pearl perfectly. My polished, black BMW was parked in front of my unwashed, brown Volkswagen Beetle. Both were ten years old. I pushed the motorcycle away from the car, exposing the car’s license plate: Eugénie.

Pearl pointed at the license plate and winced. I smiled and shrugged and started the engine. She climbed on. I put her hands around my waist and pressed them tight. I took a deep breath, smiled, and rode off.

When we arrived in Langley, my mother heard the throbbing of the engine and rushed out to greet us. Pearl climbed off the bike and took off her helmet. Unable to speak to each other, my mother and Pearl simply hugged. Father greeted Pearl with a handshake.

Pearl followed my mother into the kitchen and helped cook dinner. Father mixed a gin-and-tonic for himself while I took a beer from the refrigerator. He and I sat in the living room.

“Son, your girl is pretty, but be careful not to let your second relationship be the consequence of your first. Six months is nothing; give yourself time. I spent years working with handicapped people in charitable foundations, and from what I’ve seen, it’s difficult to go through childhood with a handicap and develop a view of the world completely free of psychological scars.”

“Like …?”

“Bitterness. Suspicion. Some deaf people and blind people can’t trust because they can’t know all that goes on around them. For some, suspicion fills that void.”

“Pearl is happier than Eugénie. She isn’t driven to live up to her mother’s and sister’s talents. Other than talk to me, she can do anything. Deafness is a language problem.”

“It’s more than that. Some handicapped people believe the world owes them a living—taxes should pay for interpreters, for example, so why learn to speak? Be careful not to be an entitlement. Do you see what I’m getting at?”

“No.”

Pearl came into the dining room jingling tableware. My mother followed her with heated plates.

“Pearl made the gravy. She’s wonderful in the kitchen.”

When we sat down to eat, I handed the notepad to my mother. She wrote to Pearl in beautiful cursive script, speaking each word as she wrote it. It was a happy evening. It was clear that were Pearl and I to become a couple, she would be warmly welcomed by my parents, despite my father’s concerns.

As we mounted the motorcycle to ride home, my mother hugged Pearl affectionately.

I said, “Isn’t she beautiful, Mom?”

A Silent Movie

“I’m glad you’re here this evening,” the instructor signed and said. “Please say your name and why you want to learn ASL.”

“I have a deaf son.”

“I work with disabled people.”

“I have a deaf nephew.”

“I am a missionary.”

“I’m a woodworking teacher. I would like to teach deaf students.”

“Good reasons! ‘My country, my language,’ they say. Well, there are two million deafies in North America, and they can’t learn to hear and join your country, but you can learn to sign and join theirs. This is what makes some deaf people militant at times.”

“I noticed,” said another student.

“They do their best to live in our deaf-impaired country, but we are not as generous to them. A global world exists of deafies communicating with each other and intermarrying. My parents are deaf, and I’m still an outsider.” The instructor looked for a reaction, then continued to sign and speak. “Native ASL is not a signed version of English. It branched off from French Sign Language when sign language was established in the US by a deaf Frenchman in the nineteenth century. Syntax and basic signs like ‘man’ and ‘woman’ are French. It’s almost as hard for an American deafie to sign to a British deafie as it is for an American hearie to speak to a French hearie. Even the fingerspelling is different! BSL needs two hands to fingerspell, ASL just one. How many of you know a few signs?”

Most of us raised our hands.

“If you aren’t sure a deafie is looking at you, then wave, touch an elbow, or stomp before you sign. And don’t let your eyes wander—it breaks the communication channel, so it’s rude. You must manage that channel to keep it open.”

“How many signs are there?” said a student.

“Five thousand. Try to learn new signs every day.”

“English has over a hundred thousand words.”

“Yes, but when you need an unusual word, you fingerspell it. I’ll sign some word pairs quickly, the equivalent of homonyms. See if you can spot the difference.” He signed several word pairs. “See the difference?”

Embarrassed, the students looked at each other. “Hardly,” said one.

“I signed, shy-whore, blue-bastard, ugly-summer, wrong-yellow, student-garbage, chocolate-church. ASL has charm every bit as rich as English.”

“I’m done for,” muttered a student.

“This beginner course focuses on signing using English syntax. When you sign ASL using English syntax, all deafies will understand you, and they will answer the same way. But when they sign to each other, they will use native ASL, and you won’t understand the details of the conversation, especially when they are going at it as fast as they can.”

I raised my hand. “How long does it take to become fluent?”

“Few hearing signers make it to native ASL unless they are born to deaf parents, they live or work among deaf people, so they see them signing to all the time, or they study it full time for a degree. The rest, with just one deaf person in the family, end up in the middle, often with a patois of ‘home signs’ unique to the family.”

“Why doesn’t native ASL converge with English ASL? Everyone would be better off,” said a student.

“Because the native syntax is more efficient. Some educated deafies prefer English ASL because it helps them with written English, but most deafies find it snobbish. For example, ‘Have you been to Toronto?’ is signed in native ASL, ‘Already touch Toronto?’—two fewer signs. Best of all, native ASL takes full advantage of dimensionality. This makes it rich and beautiful; spoken languages can’t do this. English has to use word order to indicate direction, and a pronoun like ‘he’ can only refer to one person at a time. But in ASL, we just point to a spot and sign a name to establish a ‘he’ there. Then we point to another spot and sign another name to establish another ‘he’ over there, and so on. We can have half a dozen ‘he’ pronouns in use at the same time. Then we toss verbs between those spots to indicate action. English can’t do this without confusion. To make it a question instead of a statement, you just add a quizzical look—a facial question mark. To add common adverbs, you add feeling to your signing, like fast, anger, uncertainty. One sign sequence can translate to dozens of sentences! Signed songs are like a dance with words. ASL has puns, too. Does anyone know this sign?” He made a fist and relaxed it several times.

“Milk,” said a student.

“And this?” He made the same sign but moved it past his face. “Past-your-eyes milk—pasteurized milk! Now the reality check. Although ASL richly describes anything visual, it describes abstract concepts poorly. Idioms are crucial to abstract thought, but there’s almost no idiom in ASL. Think of it this way: ASL is a

Comments (0)