The Iliad - Homer (best novels to read for beginners .txt) 📗

- Author: Homer

- Performer: -

Book online «The Iliad - Homer (best novels to read for beginners .txt) 📗». Author Homer

That the Earl of Halifax was one of the first to favour me; of whom it is hard to say whether the advancement of the polite arts is more owing to his generosity or his example: that such a genius as my Lord Bolingbroke, not more distinguished in the great scenes of business, than in all the useful and entertaining parts of learning, has not refused to be the critic of these sheets, and the patron of their writer: and that the noble author of the tragedy of “Heroic Love” has continued his partiality to me, from my writing pastorals to my attempting the Iliad. I cannot deny myself the pride of confessing, that I have had the advantage not only of their advice for the conduct in general, but their correction of several particulars of this translation.

I could say a great deal of the pleasure of being distinguished by the Earl of Carnarvon; but it is almost absurd to particularize any one generous action in a person whose whole life is a continued series of them. Mr. Stanhope, the present secretary of state, will pardon my desire of having it known that he was pleased to promote this affair.

The particular zeal of Mr. Harcourt (the son of the late Lord Chancellor) gave me a proof how much I am honoured in a share of his friendship. I must attribute to the same motive that of several others of my friends: to whom all acknowledgments are rendered unnecessary by the privileges of a familiar correspondence; and I am satisfied I can no way better oblige men of their turn than by my silence.

In short, I have found more patrons than ever Homer wanted. He would have thought himself happy to have met the same favour at Athens that has been shown me by its learned rival, the University of Oxford. And I can hardly envy him those pompous honours he received after death, when I reflect on the enjoyment of so many agreeable obligations, and easy friendships, which make the satisfaction of life. This distinction is the more to be acknowledged, as it is shown to one whose pen has never gratified the prejudices of particular parties, or the vanities of particular men. Whatever the success may prove, I shall never repent of an undertaking in which I have experienced the candour and friendship of so many persons of merit; and in which I hope to pass some of those years of youth that are generally lost in a circle of follies, after a manner neither wholly unuseful to others, nor disagreeable to myself.

THE ILIAD.

BOOK I.

ARGUMENT. [Footnote: The following argument of the Iliad, corrected in a few particulars, is translated from Bitaube, and is, perhaps, the neatest summary that has ever been drawn up:—“A hero, injured by his general, and animated with a noble resentment, retires to his tent; and for a season withdraws himself and his troops from the war. During this interval, victory abandons the army, which for nine years has been occupied in a great enterprise, upon the successful termination of which the honour of their country depends. The general, at length opening his eyes to the fault which he had committed, deputes the principal officers of his army to the incensed hero, with commission to make compensation for the injury, and to tender magnificent presents.

The hero, according to the proud obstinacy of his character, persists in his animosity; the army is again defeated, and is on the verge of entire destruction. This inexorable man has a friend; this friend weeps before him, and asks for the hero’s arms, and for permission to go to the war in his stead. The eloquence of friendship prevails more than the intercession of the ambassadors or the gifts of the general. He lends his armour to his friend, but commands him not to engage with the chief of the enemy’s army, because he reserves to himself the honour of that combat, and because he also fears for his friend’s life. The prohibition is forgotten; the friend listens to nothing but his courage; his corpse is brought back to the hero, and the hero’s arms become the prize of the conqueror. Then the hero, given up to the most lively despair, prepares to fight; he receives from a divinity new armour, is reconciled with his general and, thirsting for glory and revenge, enacts prodigies of valour, recovers the victory, slays the enemy’s chief, honours his friend with superb funeral rites, and exercises a cruel vengeance on the body of his destroyer; but finally appeased by the tears and prayers of the father of the slain warrior, restores to the old man the corpse of his son, which he buries with due solemnities.’—Coleridge, p. 177, sqq.]

THE CONTENTION OF ACHILLES AND AGAMEMNON.

In the war of Troy, the Greeks having sacked some of the neighbouring towns, and taken from thence two beautiful captives, Chryseis and Briseis, allotted the first to Agamemnon, and the last to Achilles.

Chryses, the father of Chryseis, and priest of Apollo, comes to the Grecian camp to ransom her; with which the action of the poem opens, in the tenth year of the siege. The priest being refused, and insolently dismissed by Agamemnon, entreats for vengeance from his god; who inflicts a pestilence on the Greeks. Achilles calls a council, and encourages Chalcas to declare the cause of it; who attributes it to the refusal of Chryseis. The king, being obliged to send back his captive, enters into a furious contest with Achilles, which Nestor pacifies; however, as he had the absolute command of the army, he seizes on Briseis in revenge. Achilles in discontent withdraws himself and his forces from the rest of the Greeks; and complaining to Thetis, she supplicates Jupiter to render them sensible of the wrong done to her son, by giving victory to the Trojans. Jupiter, granting her suit, incenses Juno: between whom the debate runs high, till they are reconciled by the address of Vulcan.

The time of two-and-twenty days is taken up in this book: nine during the plague, one in the council and quarrel of the princes, and twelve for Jupiter’s stay with the AEthiopians, at whose return Thetis prefers her petition. The scene lies in the Grecian camp, then changes to Chrysa, and lastly to Olympus.

Achilles’ wrath, to Greece the direful spring Of woes unnumber’d, heavenly goddess, sing!

That wrath which hurl’d to Pluto’s gloomy reign The souls of mighty chiefs untimely slain; Whose limbs unburied on the naked shore, Devouring dogs and hungry vultures tore. [1]

Since great Achilles and Atrides strove, Such was the sovereign doom, and such the will of Jove! [2]

Declare, O Muse! in what ill-fated hour [3]

Sprung the fierce strife, from what offended power Latona’s son a dire contagion spread, [4]

And heap’d the camp with mountains of the dead; The king of men his reverent priest defied, [5]

And for the king’s offence the people died.

For Chryses sought with costly gifts to gain His captive daughter from the victor’s chain.

Suppliant the venerable father stands;

Apollo’s awful ensigns grace his hands

By these he begs; and lowly bending down, Extends the sceptre and the laurel crown He sued to all, but chief implored for grace The brother-kings, of Atreus’ royal race [6]

“Ye kings and warriors! may your vows be crown’d, And Troy’s proud walls lie level with the ground.

May Jove restore you when your toils are o’er Safe to the pleasures of your native shore.

But, oh! relieve a wretched parent’s pain, And give Chryseis to these arms again;

If mercy fail, yet let my presents move, And dread avenging Phoebus, son of Jove.”

The Greeks in shouts their joint assent declare, The priest to reverence, and release the fair.

Not so Atrides; he, with kingly pride,

Repulsed the sacred sire, and thus replied: “Hence on thy life, and fly these hostile plains, Nor ask, presumptuous, what the king detains Hence, with thy laurel crown, and golden rod, Nor trust too far those ensigns of thy god.

Mine is thy daughter, priest, and shall remain; And prayers, and tears, and bribes, shall plead in vain; Till time shall rifle every youthful grace, And age dismiss her from my cold embrace, In daily labours of the loom employ’d,

Or doom’d to deck the bed she once enjoy’d Hence then; to Argos shall the maid retire, Far from her native soil and weeping sire.”

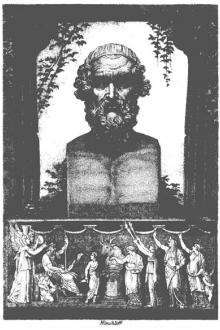

{Illustration: HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE.}

The trembling priest along the shore return’d, And in the anguish of a father mourn’d.

Disconsolate, not daring to complain,

Silent he wander’d by the sounding main; Till, safe at distance, to his god he prays, The god who darts around the world his rays.

“O Smintheus! sprung from fair Latona’s line, [7]

Thou guardian power of Cilla the divine, [8]

Thou source of light! whom Tenedos adores, And whose bright presence gilds thy Chrysa’s shores.

If e’er with wreaths I hung thy sacred fane, [9]

Or fed the flames with fat of oxen slain; God of the silver bow! thy shafts employ, Avenge thy servant, and the Greeks destroy.”

Thus Chryses pray’d.—the favouring power attends, And from Olympus’ lofty tops descends.

Bent was his bow, the Grecian hearts to wound; [10]

Fierce as he moved, his silver shafts resound.

Breathing revenge, a sudden night he spread, And gloomy darkness roll’d about his head.

The fleet in view, he twang’d his deadly bow, And hissing fly the feather’d fates below.

On mules and dogs the infection first began; [11]

And last, the vengeful arrows fix’d in man.

For nine long nights, through all the dusky air, The pyres, thick-flaming, shot a dismal glare.

But ere the tenth revolving day was run, Inspired by Juno, Thetis’ godlike son

Convened to council all the Grecian train; For much the goddess mourn’d her heroes slain. [12]

The assembly seated, rising o’er the rest, Achilles thus the king of men address’d: “Why leave we not the fatal Trojan shore, And measure back the seas we cross’d before?

The plague destroying whom the sword would spare, ‘Tis time to save the few remains of war.

But let some prophet, or some sacred sage, Explore the cause of great Apollo’s rage; Or learn the wasteful vengeance to remove By mystic dreams, for dreams descend from Jove. [13]

If broken vows this heavy curse have laid, Let altars smoke, and hecatombs be paid.

So Heaven, atoned, shall dying Greece restore, And Phoebus dart his burning shafts no more.”

He said, and sat: when Chalcas thus replied; Chalcas the wise, the Grecian priest and guide, That sacred seer, whose comprehensive view, The past, the present, and the future knew: Uprising slow, the venerable sage

Thus spoke the prudence and the fears of age: “Beloved of Jove, Achilles! would’st thou know Why angry Phoebus bends his fatal bow?

First give thy faith, and plight a prince’s word Of sure protection, by thy power and sword: For I must speak what wisdom would conceal, And truths, invidious to the great, reveal, Bold is the task, when subjects, grown too wise, Instruct a monarch where his error lies; For though we deem the short-lived fury past, ‘Tis sure the mighty will revenge at last.”

To whom Pelides:—“From thy inmost soul Speak what thou know’st, and speak without control.

E’en by that god I swear who rules the day, To whom thy hands the vows of Greece convey.

Comments (0)