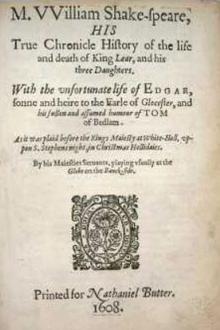

King Lear - William Shakespeare (electronic reader txt) 📗

- Author: William Shakespeare

- Performer: -

Book online «King Lear - William Shakespeare (electronic reader txt) 📗». Author William Shakespeare

France.

This is most strange,

That she, who even but now was your best object,

The argument of your praise, balm of your age,

Most best, most dearest, should in this trice of time

Commit a thing so monstrous, to dismantle

So many folds of favour. Sure her offence

Must be of such unnatural degree

That monsters it, or your fore-vouch’d affection

Fall’n into taint; which to believe of her

Must be a faith that reason without miracle

Should never plant in me.

Cor.

I yet beseech your majesty,—

If for I want that glib and oily art

To speak and purpose not; since what I well intend,

I’ll do’t before I speak,—that you make known

It is no vicious blot, murder, or foulness,

No unchaste action or dishonour’d step,

That hath depriv’d me of your grace and favour;

But even for want of that for which I am richer,—

A still-soliciting eye, and such a tongue

As I am glad I have not, though not to have it

Hath lost me in your liking.

Lear.

Better thou

Hadst not been born than not to have pleas’d me better.

France.

Is it but this,—a tardiness in nature

Which often leaves the history unspoke

That it intends to do?—My lord of Burgundy,

What say you to the lady? Love’s not love

When it is mingled with regards that stands

Aloof from the entire point. Will you have her?

She is herself a dowry.

Bur.

Royal king,

Give but that portion which yourself propos’d,

And here I take Cordelia by the hand,

Duchess of Burgundy.

Lear.

Nothing: I have sworn; I am firm.

Bur.

I am sorry, then, you have so lost a father

That you must lose a husband.

Cor.

Peace be with Burgundy!

Since that respects of fortune are his love,

I shall not be his wife.

France.

Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich, being poor;

Most choice, forsaken; and most lov’d, despis’d!

Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon:

Be it lawful, I take up what’s cast away.

Gods, gods! ‘tis strange that from their cold’st neglect

My love should kindle to inflam’d respect.—

Thy dowerless daughter, king, thrown to my chance,

Is queen of us, of ours, and our fair France:

Not all the dukes of waterish Burgundy

Can buy this unpriz’d precious maid of me.—

Bid them farewell, Cordelia, though unkind:

Thou losest here, a better where to find.

Lear.

Thou hast her, France: let her be thine; for we

Have no such daughter, nor shall ever see

That face of hers again.—Therefore be gone

Without our grace, our love, our benison.—

Come, noble Burgundy.

[Flourish. Exeunt Lear, Burgundy, Cornwall, Albany, Gloster,

and Attendants.]

France.

Bid farewell to your sisters.

Cor.

The jewels of our father, with wash’d eyes

Cordelia leaves you: I know you what you are;

And, like a sister, am most loath to call

Your faults as they are nam’d. Love well our father:

To your professed bosoms I commit him:

But yet, alas, stood I within his grace,

I would prefer him to a better place.

So, farewell to you both.

Reg.

Prescribe not us our duties.

Gon.

Let your study

Be to content your lord, who hath receiv’d you

At fortune’s alms. You have obedience scanted,

And well are worth the want that you have wanted.

Cor.

Time shall unfold what plighted cunning hides:

Who cover faults, at last shame them derides.

Well may you prosper!

France.

Come, my fair Cordelia.

[Exeunt France and Cordelia.]

Gon.

Sister, it is not little I have to say of what most nearly

appertains to us both. I think our father will hence to-night.

Reg.

That’s most certain, and with you; next month with us.

Gon.

You see how full of changes his age is; the observation we

have made of it hath not been little: he always loved our

sister most; and with what poor judgment he hath now cast her

off appears too grossly.

Reg.

‘Tis the infirmity of his age: yet he hath ever but slenderly

known himself.

Gon.

The best and soundest of his time hath been but rash; then must

we look to receive from his age, not alone the imperfections of

long-ingraffed condition, but therewithal the unruly waywardness

that infirm and choleric years bring with them.

Reg.

Such unconstant starts are we like to have from him as this of

Kent’s banishment.

Gon.

There is further compliment of leave-taking between France and

him. Pray you let us hit together: if our father carry authority

with such dispositions as he bears, this last surrender of his

will but offend us.

Reg.

We shall further think of it.

Gon.

We must do something, and i’ th’ heat.

[Exeunt.]

Scene II. A Hall in the Earl of Gloster’s Castle.

[Enter Edmund with a letter.]

Edm.

Thou, nature, art my goddess; to thy law

My services are bound. Wherefore should I

Stand in the plague of custom, and permit

The curiosity of nations to deprive me,

For that I am some twelve or fourteen moonshines

Lag of a brother? Why bastard? wherefore base?

When my dimensions are as well compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape as true

As honest madam’s issue? Why brand they us

With base? with baseness? bastardy? base, base?

Who, in the lusty stealth of nature, take

More composition and fierce quality

Than doth, within a dull, stale, tired bed,

Go to the creating a whole tribe of fops

Got ‘tween asleep and wake?—Well then,

Legitimate Edgar, I must have your land:

Our father’s love is to the bastard Edmund

As to the legitimate: fine word—legitimate!

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed,

And my invention thrive, Edmund the base

Shall top the legitimate. I grow; I prosper.—

Now, gods, stand up for bastards!

[Enter Gloster.]

Glou.

Kent banish’d thus! and France in choler parted!

And the king gone to-night! subscrib’d his pow’r!

Confin’d to exhibition! All this done

Upon the gad!—Edmund, how now! What news?

Edm.

So please your lordship, none.

[Putting up the letter.]

Glou.

Why so earnestly seek you to put up that letter?

Edm.

I know no news, my lord.

Glou.

What paper were you reading?

Edm.

Nothing, my lord.

Glou.

No? What needed, then, that terrible dispatch of it into your

pocket? the quality of nothing hath not such need to hide itself.

Let’s see.

Come, if it be nothing, I shall not need spectacles.

Edm.

I beseech you, sir, pardon me. It is a letter from my brother

that I have not all o’er-read; and for so much as I have perus’d,

I find it not fit for your o’erlooking.

Glou.

Give me the letter, sir.

Edm.

I shall offend, either to detain or give it. The contents, as in

part I understand them, are to blame.

Glou.

Let’s see, let’s see!

Edm.

I hope, for my brother’s justification, he wrote this but as an

essay or taste of my virtue.

Glou.

[Reads.] ‘This policy and reverence of age makes the world

bitter to the best of our times; keeps our fortunes from us

till our oldness cannot relish them. I begin to find an idle

and fond bondage in the oppression of aged tyranny; who sways,

not as it hath power, but as it is suffered. Come to me, that

of this I may speak more. If our father would sleep till I

waked him, you should enjoy half his revenue for ever, and live

the beloved of your brother,

‘EDGAR.’

Hum! Conspiracy?—‘Sleep till I waked him,—you should enjoy half

his revenue.’—My son Edgar! Had he a hand to write this? a heart

and brain to breed it in? When came this to you? who brought it?

Edm.

It was not brought me, my lord, there’s the cunning of it; I

found it thrown in at the casement of my closet.

Glou.

You know the character to be your brother’s?

Edm.

If the matter were good, my lord, I durst swear it were his; but

in respect of that, I would fain think it were not.

Glou.

It is his.

Edm.

It is his hand, my lord; but I hope his heart is not in the

contents.

Glou.

Hath he never before sounded you in this business?

Edm.

Never, my lord: but I have heard him oft maintain it to be fit

that, sons at perfect age, and fathers declined, the father

should be as ward to the son, and the son manage his revenue.

Glou.

O villain, villain!—His very opinion in the letter! Abhorred

villain!—Unnatural, detested, brutish villain! worse than

brutish!—Go, sirrah, seek him; I’ll apprehend him. Abominable

villain!—Where is he?

Edm.

I do not well know, my lord. If it shall please you to suspend

your indignation against my brother till you can derive from him

better testimony of his intent, you should run a certain course;

where, if you violently proceed against him, mistaking his

purpose, it would make a great gap in your own honour, and shake

in pieces the heart of his obedience. I dare pawn down my life

for him that he hath writ this to feel my affection to your

honour, and to no other pretence of danger.

Glou.

Think you so?

Edm.

If your honour judge it meet, I will place you where you shall

hear us confer of this, and by an auricular assurance have your

satisfaction;

and that without any further delay than this very evening.

Glou.

He cannot be such a monster.

Edm.

Nor is not, sure.

Glou.

To his father, that so tenderly and entirely loves him.—Heaven

and earth!—Edmund, seek him out; wind me into him, I pray you:

frame the business after your own wisdom. I would unstate myself

to be in a due resolution.

Edm.

I will seek him, sir, presently; convey the business as I shall

find means, and acquaint you withal.

Glou.

These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us:

though the wisdom of nature can reason it thus and thus, yet

nature finds itself scourged by the sequent effects: love cools,

friendship falls off, brothers divide: in cities, mutinies; in

countries, discord; in palaces, treason; and the bond cracked

‘twixt son and father. This villain of mine comes under the

prediction; there’s son against father: the king falls from

bias of nature; there’s father against child. We have seen the

best of our time: machinations, hollowness, treachery, and all

ruinous disorders follow us disquietly to our graves.—Find out

this villain, Edmund; it shall lose thee nothing; do it

carefully.—And the noble and true-hearted Kent banished! his

offence, honesty!—‘Tis strange.

[Exit.]

Edm.

This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, when we are

sick in fortune,—often the surfeit of our own behaviour,—we

make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars; as

if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion;

knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical pre-dominance;

drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of

planetary influence; and all that we are evil in, by a divine

thrusting on: an admirable evasion of whoremaster man, to lay his

goatish disposition to the charge of a star! My father compounded

with my mother under the dragon’s tail, and my nativity was under

ursa major; so that it follows I am rough and lecherous.—Tut! I

should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the

firmament twinkled on my bastardizing.

[Enter Edgar.]

Pat!—he comes, like the catastrophe of the old comedy: my cue

is villainous melancholy, with a sigh like

Comments (0)