Understood Betsy - Dorothy Canfield Fisher (autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Dorothy Canfield Fisher

- Performer: -

Book online «Understood Betsy - Dorothy Canfield Fisher (autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Dorothy Canfield Fisher

guide: “What would Cousin Ann do if she were here? She wouldn’t cry. She

would THINK of something.”

Betsy looked around her desperately. The first thing she saw was the big

limb of a pine-tree, broken off by the wind, which half lay and half

slantingly stood up against a tree a little distance above the mouth of

the pit. It had been there so long that the needles had all dried and

fallen off, and the skeleton of the branch with the broken stubs looked

like … yes, it looked like a ladder! THAT was what Cousin Ann would have

done!

“Wait a minute! Wait a minute, Molly!” she called wildly down the pit,

warm all over in excitement. “Now listen. You go off there in a corner,

where the ground makes a sort of roof. I’m going to throw down something

you can climb up on, maybe.”

“Ow! Ow, it’ll hit me!” cried poor little Molly, more and more

frightened. But she scrambled off under her shelter obediently, while

Betsy struggled with the branch. It was so firmly imbedded in the snow

that at first she could not budge it at all. But after she cleared that

away and pried hard with the stick she was using as a lever she felt it

give a little. She bore down with all her might, throwing her weight

again and again on her lever, and finally felt the big branch

perceptibly move. After that it was easier, as its course was down hill

over the snow to the mouth of the pit. Glowing, and pushing, wet with

perspiration, she slowly maneuvered it along to the edge, turned it

squarely, gave it a great shove, and leaned over anxiously. Then she

gave a great sigh of relief! Just as she had hoped, it went down sharp

end first and stuck fast in the snow which had saved Molly from broken

bones. She was so out of breath with her work that for a moment she

could not speak. Then, “Molly, there! Now I guess you can climb up to

where I can reach you.”

Molly made a rush for any way out of her prison, and climbed, like the

little practiced squirrel that she was, up from one stub to another to

the top of the branch. She was still below the edge of the pit there,

but Betsy lay flat down on the snow and held out her hands. Molly took

hold hard, and, digging her toes into the snow, slowly wormed her way up

to the surface of the ground.

It was then, at that very moment, that Shep came bounding up to them,

barking loudly, and after him Cousin Ann striding along in her rubber

boots, with a lantern in her hand and a rather anxious look on her face.

She stopped short and looked at the two little girls, covered with snow,

their faces flaming with excitement, and at the black hole gaping behind

them. “I always TOLD Father we ought to put a fence around that pit,”

she said in a matter-of-fact voice. “Some day a sheep’s going to fall

down there. Shep came along to the house without you, and we thought

most likely you’d taken the wrong turn.”

Betsy felt terribly aggrieved. She wanted to be petted and praised for

her heroism. She wanted Cousin Ann to REALIZE … oh, if Aunt Frances were

only there, SHE would realize … !

“I fell down in the hole, and Betsy wanted to go and get Mr. Putney, but

I wouldn’t let her, and so she threw down a big branch and I climbed

out,” explained Molly, who, now that her danger was past, took Betsy’s

action quite as a matter of course.

“Oh, that was how it happened,” said Cousin Ann. She looked down the

hole and saw the big branch, and looked back and saw the long trail of

crushed snow where Betsy had dragged it. “Well, now, that was quite a

good idea for a little girl to have,” she said briefly. “I guess you’ll

do to take care of Molly all right!”

She spoke in her usual voice and immediately drew the children after

her, but Betsy’s heart was singing joyfully as she trotted along

clasping Cousin Ann’s strong hand. Now she knew that Cousin Ann

realized. … She trotted fast, smiling to herself in the darkness.

“What made you think of doing that?” asked Cousin Ann presently, as they

approached the house.

“Why, I tried to think what YOU would have done if you’d been there,”

said Betsy.

“Oh!” said Cousin Ann. “Well …”

She didn’t say another word, but Betsy, glancing up into her face as

they stepped into the lighted room, saw an expression that made her give

a little skip and hop of joy. She had PLEASED Cousin Ann.

That night, as she lay in her bed, her arm over Molly cuddled up warm

beside her, she remembered, oh, ever so faintly, as something of no

importance, that she had failed in an examination that afternoon.

BETSY STARTS A SEWING SOCIETY

Betsy and Molly had taken Deborah to school with them. Deborah was the

old wooden doll with brown, painted curls. She had lain in a trunk

almost ever since Aunt Abigail’s childhood, because Cousin Ann had never

cared for dolls when she was a little girl. At first Betsy had not dared

to ask to see her, much less to play with her, but when Ellen, as she

had promised, came over to Putney Farm that first Saturday she had said

right out, as soon as she landed in the house, “Oh, Mrs. Putney, can’t

we play with Deborah?” And Aunt Abigail had answered: “Why YES, of

course! I KNEW there was something I’ve kept forgetting!” She went up

with them herself to the cold attic and opened the little hair-trunk

under the eaves.

There lay a doll, flat on her back, looking up at them brightly out of

her blue eyes.

“Well, Debby dear,” said Aunt Abigail, taking her up gently. “It’s a

good long time since you and I played under the lilac bushes, isn’t it?

I expect you’ve been pretty lonesome up here all these years. Never you

mind, you’ll have some good times again, now.” She pulled down the

doll’s full, ruffled skirt, straightened the lace at the neck of her

dress, and held her for a moment, looking down at her silently. You

could tell by the way she spoke, by the way she touched Deborah, by the

way she looked at her, that she had loved the doll very dearly, and

maybe still did, a little.

When she put Deborah into Betsy’s arms, the child felt that she was

receiving something very precious, almost something alive. She and Ellen

looked with delight at the yards and yards of picot-edged ribbon, sewed

on by hand to the ruffles of the skirt, and lifted up the silk folds to

admire the carefully made, full petticoats and frilly drawers, the

pretty, soft old kid shoes and white stockings. Aunt Abigail looked at

them with an absent smile on her lips, as though she were living over

old scenes.

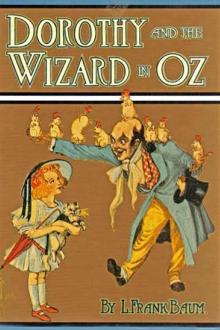

[Illustration: Betsy and Ellen and the old doll.]

Finally, “It’s too cold to play up here,” she said, coming to herself

with a long breath. “You’d better bring Deborah and the trunk down into

the south room.” She carried the doll, and Betsy and Ellen each took an

end of the old trunk, no larger than a modern suitcase. They settled

themselves on the big couch, back of the table with the lamp. Old Shep

was on it, but Betsy coaxed him off by putting down some bones Cousin

Ann had been saving for him. When he finished those and came back for

the rest of his snooze, he found his place occupied by the little girls,

sitting cross-legged, examining the contents of the trunk, all spread

out around them. Shep sighed deeply and sat down with his nose resting

on the couch near Betsy’s knee, following all their movements with his

kind, dark eyes. Once in a while Betsy stopped hugging Deborah or

exclaiming over a new dress long enough to pat Shep’s head and fondle

his ears. This was what he was waiting for, and every time she did it he

wagged his tail thumpingly against the floor.

After that Deborah and her trunk were kept downstairs where Betsy could

play with her. And often she was taken to school. You never heard of

such a thing as taking a doll to school, did you? Well, I told you this

was a queer, old-fashioned school that any modern School Superintendent

would sniff at. As a matter of fact, it was not only Betsy who took her

doll to school; all the little girls did, whenever they felt like it.

Miss Benton, the teacher, had a shelf for them in the entry-way where

the wraps were hung, and the dolls sat on it and waited patiently all

through lessons. At recess time or nooning each little mother snatched

her own child and began to play. As soon as it grew warm enough to play

outdoors without just racing around every minute to keep from freezing

to death, the dolls and their mothers went out to a great pile of rocks

at one end of the bare, stony field which was the playground.

There they sat and played in the spring sunshine, warmer from day to

day. There were a great many holes and shelves and pockets and little

caves in the rocks which made lovely places for playing keep-house. Each

little girl had her own particular cubby-holes and “rooms,” and they

“visited” their dolls back and forth all around the pile. And as they

played they talked very fast about all sorts of things, being little

girls and not boys who just yelled and howled inarticulately as they

played ball or duck-on-a-rock or prisoner’s goal, racing and running and

wrestling noisily all around the rocks.

There was one child who neither played with the girls nor ran and

whooped with the boys. This was little six-year-old ‘Lias, one of the

two boys in Molly’s first grade. At recess time he generally hung about

the school door by himself, looking moodily down and knocking the toe of

his ragged, muddy shoe against a stone. The little girls were talking

about him one day as they played. “My! Isn’t that ‘Lias Brewster the

horridest-looking child!” said Eliza, who had the second grade all to

herself, although Molly now read out of the second reader with her.

“Mercy, yes! So ragged!” said Anastasia Monahan, called Stashie for

short. She was a big girl, fourteen years old, who was in the seventh

grade.

“He doesn’t look as if he EVER combed his hair!” said Betsy. “It looks

just like a wisp of old hay.”

“And sometimes,” little Molly proudly added her bit to the talk of the

older girls, “he forgets to put on any stockings and just has his

dreadful old shoes on over his dirty, bare feet.”

“I guess he hasn’t GOT any stockings half the time,” said big Stashie

scornfully. “I guess his stepfather drinks ‘em up.”

“How CAN he drink up stockings!” asked Molly, opening her round eyes

very wide.

“Sh! You mustn’t ask. Little girls shouldn’t know about such things,

should they, Betsy?”

“No INDEED,” said Betsy, looking mysterious. As a matter of fact, she

herself had no idea what Stashie meant, but she looked wise and said

nothing.

Some of the boys had squatted down near the rocks for a game of marbles

now.

“Well, anyhow,” said Molly resentfully, “I don’t care what his

Comments (0)