Understood Betsy - Dorothy Canfield Fisher (autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Dorothy Canfield Fisher

- Performer: -

Book online «Understood Betsy - Dorothy Canfield Fisher (autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Dorothy Canfield Fisher

seemed so lively and cheerful and gay before, seemed now a horrible,

frightening, noisy place, full of hurried strangers who came and went

their own ways, with not a glance out of their hard eyes for two little

girls stranded far from home.

The bright-colored young man was no better when they found him again. He

stopped his whistling only long enough to say, “Nope, no Will Vaughan

anywhere around these diggings yet.”

“We were going home with the Vaughans,” murmured Betsy, in a low tone,

hoping for some help from him.

“Looks as though you’d better go home on the cars,” advised the young

man casually. He smoothed his black hair back straighter than ever from

his forehead and looked over their heads.

“How much does it cost to go to Hillsboro on the cars?” asked Betsy with

a sinking heart.

“You’ll have to ask somebody else about that,” said the young man. “What

I don’t know about this Rube state! I never was in it before.” He spoke

as though he were very proud of the fact.

Betsy turned and went over to the older man who had told them about the

Vaughans.

Molly trotted at her heels, quite comforted, now that Betsy was talking

so competently to grown-ups. She did not hear what they said, nor try

to. Now that Betsy’s voice sounded all right she had no more fears.

Betsy would manage somehow. She heard Betsy’s voice again talking to the

other man, but she was busy looking at an exhibit of beautiful jelly

glasses, and paid no attention. Then Betsy led her away again out of

doors, where everybody was walking back and forth under the bright

September sky, blowing on horns, waving plumes of brilliant tissue-paper, tickling each other with peacock feathers, and eating pop-corn

and candy out of paper bags.

That reminded Molly that they had ten cents yet. “Oh, Betsy,” she

proposed, “let’s take a nickel of our money for some pop-corn.”

She was startled by Betsy’s fierce sudden clutch at their little purse

and by the quaver in her voice as she answered: “No, no, Molly. We’ve

got to save every cent of that. I’ve found out it costs thirty cents for

us both to go home to Hillsboro on the train. The last one goes at six

o’clock.”

“We haven’t got but ten,” said Molly.

Betsy looked at her silently for a moment and then burst out, “I’ll earn

the rest! I’ll earn it somehow! I’ll have to! There isn’t any other

way!”

“All right,” said Molly quaintly, not seeing anything unusual in this.

“You can, if you want to. I’ll wait for you here.”

“No, you won’t!” cried Betsy, who had quite enough of trying to meet

people in a crowd. “No, you won’t! You just follow me every minute! I

don’t want you out of my sight!”

They began to move forward now, Betsy’s eyes wildly roving from one

place to another. How COULD a little girl earn money at a county fair!

She was horribly afraid to go up and speak to a stranger, and yet how

else could she begin?

“Here, Molly, you wait here,” she said. “Don’t you budge till I come

back.”

But alas! Molly had only a moment to wait that time, for the man who was

selling lemonade answered Betsy’s shy question with a stare and a curt,

“Lord, no! What could a young one like you do for me?”

The little girls wandered on, Molly calm and expectant, confident in

Betsy; Betsy with a very dry mouth and a very gone feeling. They were

passing by a big shed-like building now, where a large sign proclaimed

that the Woodford Ladies’ Aid Society would serve a hot chicken dinner

for thirty-five cents. Of course the sign was not accurate, for at half-past three, almost four, the chicken dinner had long ago been all eaten

and in place of the diners was a group of weary women moving languidly

about or standing saggingly by a great table piled with dirty dishes.

Betsy paused here, meditated a moment, and went in rapidly so that her

courage would not evaporate.

The woman with gray hair looked down at her a little impatiently and

said, “Dinner’s all over.”

“I didn’t come for dinner,” said Betsy, swallowing hard. “I came to see

if you wouldn’t hire me to wash your dishes. I’ll do them for twenty-five cents.”

The woman laughed, looked from little Betsy to the great pile of dishes,

and said, turning away, “Mercy, child, if you washed from now till

morning, you wouldn’t make a hole in what we’ve got to do.”

Betsy heard her say to the other women, “Some young one wanting more

money for the side-shows.”

Now, now was the moment to remember what Cousin Ann would have done. She

would certainly not have shaken all over with hurt feelings nor have

allowed the tears to come stingingly to her eyes. So Betsy sternly made

herself stop doing these things. And Cousin Ann wouldn’t have given way

to the dreadful sinking feeling of utter discouragement, but would have

gone right on to the next place. So, although Betsy felt like nothing so

much as crooking her elbow over her face and crying as hard as she could

cry, she stiffened her back, took Molly’s hand again, and stepped out,

heart-sick within but very steady (although rather pale) without.

She and Molly walked along in the crowd again, Molly laughing and

pointing out the pranks and antics of the young people, who were feeling

livelier than ever as the afternoon wore on. Betsy looked at them grimly

with unseeing eyes. It was four o’clock. The last train for Hillsboro

left in two hours and she was no nearer having the price of the tickets.

She stopped for a moment to get her breath; for, although they were

walking slowly, she kept feeling breathless and choked. It occurred to

her that if ever a little girl had had a more horrible birthday she

never heard of one!

“Oh, I wish I could, Dan!” said a young voice near her. “But honest!

Momma’d just eat me up alive if I left the booth for a minute!”

Betsy turned quickly. A very pretty girl with yellow hair and blue eyes

(she looked as Molly might when she was grown up) was leaning over the

edge of a little canvas-covered booth, the sign of which announced that

home-made doughnuts and soft drinks were for sale there. A young man,

very flushed and gay, was pulling at the girl’s blue gingham sleeve.

“Oh, come on, Annie. Just one turn! The floor’s elegant. You can keep an

eye on the booth from the hall! Nobody’s going to run away with the old

thing anyhow!”

“Honest, I’d love to! But I got a great lot of dishes to wash, too! You

know Momma!” She looked longingly toward the open-air dancing floor, out

from which just then floated a burst of brazen music.

“Oh, PLEASE!” said a small voice. “I’ll do it for twenty cents.”

Betsy stood by the girl’s elbow, all quivering earnestness.

“Do what, kiddie?” asked the girl in a good-natured surprise.

“Everything!” said Betsy, compendiously. “Everything! Wash the dishes,

tend the booth; YOU can go dance! I’ll do it for twenty cents.”

The eyes of the girl and the man met in high amusement. “My! Aren’t we

up and coming!” said the man. “You’re most as big as a pint-cup, aren’t

you?” he said to Betsy.

The little girl flushed—she detested being laughed at—but she looked

straight into the laughing eyes. “I’m ten years old today,” she said,

“and I can wash dishes as well as anybody.” She spoke with dignity.

The young man burst out into a great laugh.

“Great kid, what!” he said to the girl, and then, “Say, Annie, why not?

Your mother won’t be here for an hour. The kid can keep folks from

walking off with the dope and …”

“I’ll do the dishes, too,” repeated Betsy, trying hard not to mind being

laughed at, and keeping her eyes fixed steadily on the tickets to

Hillsboro.

“Well, by gosh,” said the young man, laughing. “Here’s our chance,

Annie, for fair! Come along!”

The girl laughed, too, out of high spirits. “Wouldn’t Momma be crazy!”

she said hilariously. “But she’ll never know. Here, you cute kid, here’s

my apron.” She took off her long apron and tied it around Betsy’s neck.

“There’s the soap, there’s the table. You stack the dishes up on that

counter.”

She was out of the little gate in the counter in a twinkling, just as

Molly, in answer to a beckoning gesture from Betsy, came in. “Hello,

there’s another one!” said the gay young man, gayer and gayer. “Hello,

button! What you going to do? I suppose when they try to crack the safe

you’ll run at them and bark and drive them away!”

Molly opened her sweet, blue eyes very wide, not understanding a single

word. The girl laughed, swooped back, gave Molly a kiss, and

disappeared, running side by side with the young man toward the dance

hall.

Betsy mounted on a soap box and began joyfully to wash the dishes. She

had never thought that ever in her life would she simply LOVE to wash

dishes beyond anything else! But it was so. Her relief was so great that

she could have kissed the coarse, thick plates and glasses as she washed

them.

“It’s all right, Molly; it’s all right!” she quavered exultantly to

Molly over her shoulder. But as Molly had not (from the moment Betsy

took command) suspected that it was not all right, she only nodded and

asked if she might sit up on a barrel where she could watch the crowd go

by.

“I guess you could. I don’t know why NOT,” said Betsy doubtfully. She

lifted her up and went back to her dishes. Never were dishes washed

better!

“Two doughnuts, please,” said a man’s voice behind her.

Oh, mercy, there was somebody come to buy! Whatever should she do? She

came forward intending to say that the owner of the booth was away and

she didn’t know anything about … but the man laid down a nickel, took

two doughnuts, and turned away. Betsy gasped and looked at the home-made

sign stuck into the big pan of doughnuts. Sure enough, it read “2 for

5.” She put the nickel up on a shelf and went back to her dishwashing.

Selling things wasn’t so hard, she reflected.

As her hunted feeling of desperation relaxed she began to find some fun

in her new situation, and when a woman with two little boys approached

she came forward to wait on her, elated, important. “Two for five,” she

said in a businesslike tone. The woman put down a dime, took up four

doughnuts, divided them between her sons, and departed.

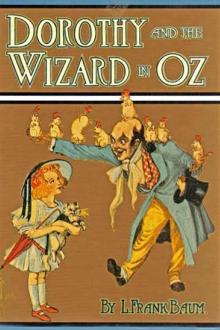

[Illustration: Never were dishes washed better!]

“My!” said Molly, looking admiringly at Betsy’s coolness over this

transaction. Betsy went back to her dishes, stepping high.

“Oh, Betsy, see! The pig! The big ox!” cried Molly now, looking from her

coign of vantage down the wide, grass-grown lane between the booths.

Betsy craned her head around over her shoulder, continuing

conscientiously to wash and wipe the dishes. The prize stock was being

paraded around the Fair; the great prize ox, his shining horns tipped

with blue rosettes; the prize cows, with wreaths around their necks; the

prize horses, four or five of them as glossy as satin, curving their

bright, strong necks and

Comments (0)