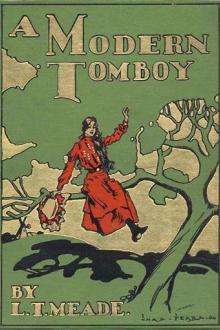

A Modern Tomboy - L. T. Meade (best fiction books to read txt) 📗

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Book online «A Modern Tomboy - L. T. Meade (best fiction books to read txt) 📗». Author L. T. Meade

"I know that, dear," said Professor Merriman; and he looked with kind eyes at the fine, brave girl who stood upright before him.

Mrs. Merriman and Miss Frost also agreed to Rosamund's suggestion, and in consequence there was a certain amount of peace in the school. This peace might have gone on, and things might have proved eminently satisfactory, had it not been for Lucy herself. But Lucy could now scarcely contain her feelings. Rosamund exceeded her in power of acquiring knowledge; she excelled her in grace and beauty. And now there was Rosamund's friend, a much younger girl, who in some ways was already Lucy's superior; for Irene had a talent for music that amounted to genius, whereas Lucy's music was inclined to be merely formal, although very correct. There were other things, too, that little Irene could pick up even at a word or a glance. Agnes did not much matter; her talents were quite ordinary. She was just a loving and lovable little child, that was all; but when Lucy sometimes met a glance of triumph in Rosamund's dark eyes, and saw the light dancing in Irene's, she began to turn round and plan for herself how she could work out a very pretty little scheme of revenge.

Now, there seemed no more secure way of doing this than by detaching little Agnes from Irene; for, however naughty Irene might be, however careless at her tasks, one glance at her little companion had always the effect of soothing her. Suppose Lucy were to make little Agnes her friend? That certainly would seem a very simple motive; for Lucy, in reality, was not interested in small children. She acknowledged that Agnes had more charm than most of her companions, and, in short, she was worth winning.

"The first thing I must do is to detach her from Irene. She does not know anything about Irene at present, but I can soon open her eyes," thought Lucy to herself.

The school began, as almost all schools do, toward the middle of September, and it was on a certain afternoon in a very sunny and warm October that Lucy invited little Agnes Frost to take a walk with her. She did this feeling sure that the child would come willingly, for both Irene and Rosamund were spending the half-holiday at The Follies. Miss Frost was busily engaged, and beginning to enjoy her life, and little Agnes was standing in her wistful way by one of the doors of the schoolroom when Lucy came by.

"Why, Agnes," said Lucy, "have you no one to play with?"

"Oh, yes, I have every one," said Agnes, raising her eyes, which appealed to all hearts; "only my darling Irene is away, and I miss her."

"Well, you can't expect her to be always with you—can you?"

"Of course not. It is very selfish of me; but I miss her all the same."

"Now, suppose," said Lucy suddenly—"suppose you take me as your friend this afternoon. What shall we do? I am a good bit older than you, but I am fond of little girls."

Agnes looked at Lucy. In truth, she had never disliked any one; but Lucy Merriman was as little to her taste as any girl could be.

"There's Agnes Sparkes. Perhaps she wouldn't mind playing with me," said she after a pause.

"As you please, child. If you prefer Agnes you can go and search for her."

"No, no, I don't," said Agnes, who wouldn't hurt a fly if she could help it. "I will go for a walk with you, Miss Merriman."

"Lucy, if you please," said Lucy. "We are both school-fellows, are we not?"

"Only I feel so very small, and so very nothing at all beside you," replied Agnes.

"But you are a good deal beside me. It is true you are small; but how old are you?"

"I was eleven my last birthday. I am two years younger than dear Irene; but Irene says that I am ten years older than she is in some ways."

"Twenty—thirty—forty, I should say," remarked Lucy, with a laugh. "Well, come along; let's have a good time. What shall we do?"

"Whatever you like—Lucy," said the little girl, making a pause before she ventured on the Christian name.

"That's right. I am glad you called me Lucy. We all like you, little Agnes; and it isn't in every school where the sister of one of the governesses would be tolerated as you are tolerated here."

"I don't quite understand what you mean by that."

"Well, your sister is one of the governesses."

"Yes, I know."

"And yet we are all very fond of you."

"It is very kind of you; but they were all fond of me at Mrs. England's school; and when I was at that sort of school at Mrs. Henderson's, where there were boys as well as girls, the girls used to quarrel with the boys as to who was to play with me. People have always been kind to me. I don't exactly know why."

"But I do, I think," said Lucy; "because you are taking, and can make people love you. It is a great gift. Now, give me your hand. We'll walk along by the riverside. It's so pretty there, is it not?"

"Yes, lovely," said little Agnes.

Lucy walked fast. Presently they sat down on a low mossy bank, and Lucy spread out her skirt so that Agnes might sit on it, so as to avoid any chance of taking a chill.

"You see how careful I am of you," said the elder girl.

"All the girls are careful of me like that," said little Agnes. "I don't exactly know why. Am I so very, very precious?"

"I expect you are to those who love you," said Lucy, coming more and more under the glamour of little Agnes's strange power of inspiring affection.

"When you look at me like that you seem quite kind, but sometimes you don't look very kind; and then, you are not fond of my darling Irene and my dearest Rosamund. I wonder why?"

"Shall I tell you?"

Lucy bent close to the little girl.

"Oh! if it is anything nasty I would rather not know."

"But I think you ought to know about your Irene. Nobody loved her at all—nobody could bear her—until——Why, what is the matter, child?"

"Don't—don't go on; I won't listen," said little Agnes.

Her face was as white as death; her eyes were dilated.

"But I will tell you," said Lucy. "She was the dreadful girl who nearly drowned poor Miss Carter, one of her governess, who is now at the Singletons'. She was the terrible, terrible girl who made your own dear sister swallow live insects instead of pills; she was the awful girl who used to put toads into the bread-pan; and—oh! I can't tell you all the terrific things she did. She is only biding her time to do the same to you. Some people say she isn't a girl at all, but a sort of fairy; and fairies always fascinate people, and when they have made them love them like anything they will turn them into wicked fairies, or something else awful. What is the matter, child?"

For little Agnes was trembling all over. After a minute she got up and made a great effort to steady herself.

"I don't think you should have told me that story," she said. "And I don't believe you."

"You don't believe me, you little wretch!" said Lucy, reddening with anger. "How dare you say such things? Do you think I, the daughter of Professor Ralph Merriman, would tell lies?"

"Well, you've told one now," said Agnes stoutly; "for I don't believe my darling Irene ever did such naughty—such very naughty—things."

"You ask Miss Frost—your dear Emily, as you call her. Here she comes walking along the bank. You go up and ask her, and if she tells you that I am wrong, then I will confess that some one told me lies. There, go at once and do it."

Miss Frost approached the pair to take little Agnes off Lucy's hands, for it did not occur to her as possible that a girl of Lucy Merriman's type could be really interested in her little sister. When she saw the white face and trembling lips, and the anxious eyes, she stopped suddenly, her own heart beating violently.

"What is it, Aggie? What is wrong, darling?" she said; and she bent down and touched the little one on the shoulder.

"Oh, Emmie, it isn't true—it can't be true!" said little Agnes.

"I have been telling her one or two things," said Lucy. "I have thought it best to put her on her guard. You have done an exceedingly silly thing to allow her to sleep in the room with that changeling sort of girl, Irene Ashleigh. Some day little Agnes will get a great fright. She says that she doesn't believe me; but you can tell her the truth, can't you? You did swallow wood-lice, did you not?"

"I—I would rather not speak of it," said Miss Frost. "It is all over now." But she shuddered as she spoke.

"Nevertheless, you must tell her. The child will not believe me."

"It was a long time ago, darling. Oh, Lucy, what have you done? What mischief you have done! How could you be so unkind?"

For little Agnes, in a perfect agony of weeping, had thrown herself into her sister's arms.

"I—I don't believe it!" she said. "Irene! Dearest, dearest Irene! She couldn't do anything of that sort."

"She couldn't now, Aggie. Oh, Lucy, do go away! Leave her to me—leave her to me," said Miss Frost, in the greatest distress.

Having accomplished her mission—and, as she said to herself, brought gunpowder into the enemy's camp—Lucy retired, wondering that she did not feel more satisfied. Agnes and her sister had a very long talk, the end of which was that they returned home a short time after Irene and Rosamund had come back from The Follies.

Irene began at once to call for Agnes.

"Aggie! Where's my Aggie? Aggie, I have brought you something back—something ever so pretty!"

But there was no response, and Irene felt a queer sensation at her heart.

"Where is the child?" she said. "Where is my little Agnes?"

After a time Agnes was seen running towards her. She did not come quite as fast as usual, and there was a change in her face. Irene did not know when she saw that change why a sudden sense of fear stole over her. It was as though some one had snatched the heart out of a gem, the glory out of a flower. It was as though little Agnes was no longer the beautiful Agnes she loved. She could not analyze her own feelings. She herself had returned in the best of spirits. Rosamund had been so bright, so cheery, so brave; her mother had been so pleased at the reports which Irene's different masters and mistresses had given her. All seemed going prosperously and well, and on the way home Rosamund had spoken of Agnes, and said how glad she was that Irene should have the little one to look after, to love and to guide and to cherish. Altogether, Irene was in her most softened mood, and she had brought back to Sunnyside several old toys of her own which she had rooted out of a cupboard in the long-disused nursery. They would charm little Agnes; they had never had any fascination for her.

She thrust the parcel into the child's hands.

"They are for you," she said.

Little Agnes took the parcel, but not in her usual frank, enthusiastic, and open delight, but timidly.

"They're not—they're not toads?" she said.

"Toads!" cried Irene; and then she colored crimson. "Don't take them unless you want them," she said; and she snatched the parcel away from the child.

Little Agnes burst out crying.

"Irene, what do you mean?—Surely, Agnes, you are not silly!" exclaimed Rosamund. "See, let me open the parcel."

"I don't want her to have it unless she really wishes for it," said Irene.

Comments (0)