Lilith - George MacDonald (distant reading txt) 📗

- Author: George MacDonald

- Performer: -

Book online «Lilith - George MacDonald (distant reading txt) 📗». Author George MacDonald

"What matters it for me? I love them; and love works no evil. I will go."

But the truth was, I forgot the children, infatuate with the horse.

Eyes flashed through the darkness, and I knew that Adam stood in his own shape beside me. I knew also by his voice that he repressed an indignation almost too strong for him.

"Mr. Vane," he said, "do you not know why you have not yet done anything worth doing?"

"Because I have been a fool," I answered.

"Wherein?"

"In everything."

"Which do you count your most indiscreet action?"

"Bringing the princess to life: I ought to have left her to her just fate."

"Nay, now you talk foolishly! You could not have done otherwise than you did, not knowing she was evil!--But you never brought any one to life! How could you, yourself dead?"

"I dead?" I cried.

"Yes," he answered; "and you will be dead, so long as you refuse to die."

"Back to the old riddling!" I returned scornfully.

"Be persuaded, and go home with me," he continued gently. "The most--nearly the only foolish thing you ever did, was to run from our dead."

I pressed the horse's ribs, and he was off like a sudden wind. I gave him a pat on the side of the neck, and he went about in a sharp-driven curve, "close to the ground, like a cat when scratchingly she wheels about after a mouse," leaning sideways till his mane swept the tops of the heather.

Through the dark I heard the wings of the raven. Five quick flaps I heard, and he perched on the horse's head. The horse checked himself instantly, ploughing up the ground with his feet.

"Mr. Vane," croaked the raven, "think what you are doing! Twice already has evil befallen you--once from fear, and once from heedlessness: breach of word is far worse; it is a crime."

"The Little Ones are in frightful peril, and I brought it upon them!" I cried. "--But indeed I will not break my word to you. I will return, and spend in your house what nights--what days--what years you please."

"I tell you once more you will do them other than good if you go to-night," he insisted.

But a false sense of power, a sense which had no root and was merely vibrated into me from the strength of the horse, had, alas, rendered me too stupid to listen to anything he said!

"Would you take from me my last chance of reparation?" I cried. "This time there shall be no shirking! It is my duty, and I will go--if I perish for it!"

"Go, then, foolish boy!" he returned, with anger in his croak. "Take the horse, and ride to failure! May it be to humility!"

He spread his wings and flew. Again I pressed the lean ribs under me.

"After the spotted leopardess!" I whispered in his ear.

He turned his head this way and that, snuffing the air; then started, and went a few paces in a slow, undecided walk. Suddenly he quickened his walk; broke into a trot; began to gallop, and in a few moments his speed was tremendous. He seemed to see in the dark; never stumbled, not once faltered, not once hesitated. I sat as on the ridge of a wave. I felt under me the play of each individual muscle: his joints were so elastic, and his every movement glided so into the next, that not once did he jar me. His growing swiftness bore him along until he flew rather than ran. The wind met and passed us like a tornado.

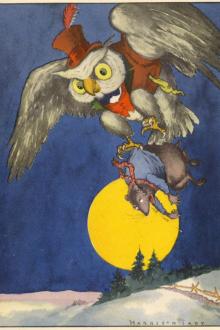

Across the evil hollow we sped like a bolt from an arblast. No monster lifted its neck; all knew the hoofs that thundered over their heads! We rushed up the hills, we shot down their farther slopes; from the rocky chasms of the river-bed he did not swerve; he held on over them his fierce, terrible gallop. The moon, half-way up the heaven, gazed with a solemn trouble in her pale countenance. Rejoicing in the power of my steed and in the pride of my life, I sat like a king and rode.

We were near the middle of the many channels, my horse every other moment clearing one, sometimes two in his stride, and now and then gathering himself for a great bounding leap, when the moon reached the key-stone of her arch. Then came a wonder and a terror: she began to descend rolling like the nave of Fortune's wheel bowled by the gods, and went faster and faster. Like our own moon, this one had a human face, and now the broad forehead now the chin was uppermost as she rolled. I gazed aghast.

Across the ravines came the howling of wolves. An ugly fear began to invade the hollow places of my heart; my confidence was on the wane! The horse maintained his headlong swiftness, with ears pricked forward, and thirsty nostrils exulting in the wind his career created. But there was the moon jolting like an old chariot-wheel down the hill of heaven, with awful boding! She rolled at last over the horizon-edge and disappeared, carrying all her light with her.

The mighty steed was in the act of clearing a wide shallow channel when we were caught in the net of the darkness. His head dropped; its impetus carried his helpless bulk across, but he fell in a heap on the margin, and where he fell he lay. I got up, kneeled beside him, and felt him all over. Not a bone could I find broken, but he was a horse no more. I sat down on the body, and buried my face in my hands.

CHAPTER XXXII

THE LOVERS AND THE BAGS

Bitterly cold grew the night. The body froze under me. The cry of the wolves came nearer; I heard their feet soft-padding on the rocky ground; their quick panting filled the air. Through the darkness I saw the many glowing eyes; their half-circle contracted around me. My time was come! I sprang to my feet.--Alas, I had not even a stick!

They came in a rush, their eyes flashing with fury of greed, their black throats agape to devour me. I stood hopelessly waiting them. One moment they halted over the horse--then came at me.

With a sound of swiftness all but silence, a cloud of green eyes came down on their flank. The heads that bore them flew at the wolves with a cry feebler yet fiercer than their howling snarl, and by the cry I knew them: they were cats, led by a huge gray one. I could see nothing of him but his eyes, yet I knew him--and so knew his colour and bigness. A terrific battle followed, whose tale alone came to me through the night. I would have fled, for surely it was but a fight which should have me!--only where was the use? my first step would be a fall! and my foes of either kind could both see and scent me in the dark!

All at once I missed the howling, and the caterwauling grew wilder. Then came the soft padding, and I knew it meant flight: the cats had defeated the wolves! In a moment the sharpest of sharp teeth were in my legs; a moment more and the cats were all over me in a live cataract, biting wherever they could bite, furiously scratching me anywhere and everywhere. A multitude clung to my body; I could not flee. Madly I fell on the hateful swarm, every finger instinct with destruction. I tore them off me, I throttled at them in vain: when I would have flung them from me, they clung to my hands like limpets. I trampled them under my feet, thrust my fingers in their eyes, caught them in jaws stronger than theirs, but could not rid myself of one. Without cease they kept discovering upon me space for fresh mouthfuls; they hauled at my skin with the widespread, horribly curved pincers of clutching claws; they hissed and spat in my face--but never touched it until, in my despair, I threw myself on the ground, when they forsook my body, and darted at my face. I rose, and immediately they left it, the more to occupy themselves with my legs. In an agony I broke from them and ran, careless whither, cleaving the solid dark. They accompanied me in a surrounding torrent, now rubbing, now leaping up against me, but tormenting me no more. When I fell, which was often, they gave me time to rise; when from fear of falling I slackened my pace, they flew afresh at my legs. All that miserable night they kept me running--but they drove me by a comparatively smooth path, for I tumbled into no gully, and passing the Evil Wood without seeing it, left it behind in the dark. When at length the morning appeared, I was beyond the channels, and on the verge of the orchard valley. In my joy I would have made friends with my persecutors, but not a cat was to be seen. I threw myself on the moss, and fell fast asleep.

I was waked by a kick, to find myself bound hand and foot, once more the thrall of the giants!

"What fitter?" I said to myself; "to whom else should I belong?" and I laughed in the triumph of self-disgust. A second kick stopped my false merriment; and thus recurrently assisted by my captors, I succeeded at length in rising to my feet.

Six of them were about me. They undid the rope that tied my legs together, attached a rope to each of them, and dragged me away. I walked as well as I could, but, as they frequently pulled both ropes at once, I fell repeatedly, whereupon they always kicked me up again. Straight to my old labour they took me, tied my leg-ropes to a tree, undid my arms, and put the hateful flint in my left hand. Then they lay down and pelted me with fallen fruit and stones, but seldom hit me. If I could have freed my legs, and got hold of a stick I spied a couple of yards from me, I would have fallen upon all six of them! "But the Little Ones will come at night!" I said to myself, and was comforted.

All day I worked hard. When the darkness came, they tied my hands, and left me fast to the tree. I slept a good deal, but woke often, and every time from a dream of lying in the heart of a heap of children. With the morning my enemies reappeared, bringing their kicks and their bestial company.

It was about noon, and I was nearly failing from fatigue and hunger, when I heard a sudden commotion in the brushwood, followed by a burst of the bell-like laughter so dear to my heart. I gave a loud cry of delight and welcome. Immediately rose a trumpeting as of baby-elephants, a neighing as of foals, and a bellowing as of calves, and through the bushes came a crowd of Little Ones, on diminutive horses, on small elephants, on little bears; but the noises came from the riders, not the animals. Mingled with the mounted ones walked the bigger of the boys and girls, among the latter a woman with a baby crowing in her arms. The giants sprang to their lumbering feet, but were instantly saluted with a storm of sharp stones; the horses charged their legs; the bears rose and hugged them at the waist; the elephants threw their trunks round their necks, pulled them down, and gave them such a trampling as they had sometimes given, but never received before. In a moment my ropes were undone, and I was in

Comments (0)