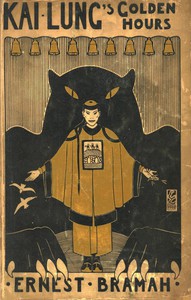

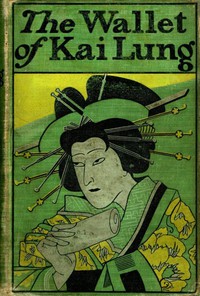

Kai Lung's Golden Hours by Ernest Bramah (books to read for 12 year olds TXT) 📗

- Author: Ernest Bramah

Book online «Kai Lung's Golden Hours by Ernest Bramah (books to read for 12 year olds TXT) 📗». Author Ernest Bramah

“Nevertheless,” replied Hien, in a violent access of self-contempt, “it is a name of abandoned omen and is destined only to reach the ears of posterity to embellish the proverb of scorn, ‘The lame duck should avoid the ploughed field.’ Can there—can there by no chance have been some hope-inspiring error?”

“Thus were the names inscribed on the parchment which after the public announcement will be affixed to the Hall of Ten Thousand Lustres,” replied Fa Fei. “With her own unworthy eyes this incapable person beheld it.”

“The name ‘Hien’ is in no way striking or profound,” continued the one in question, endeavouring to speak as though the subject referred to some person standing at a considerable distance away. “Furthermore, so commonplace and devoid of character are its written outlines that it has very much the same appearance whichever way up it is looked at.... The possibility that in your graceful confusion you held the list in such a position that what appeared to be the end was in reality the beginning is remote in the extreme, yet—”

In spite of an absorbing affection Fa Fei could not disguise from herself that her feelings would have been more pleasantly arranged if her lover had been inspired to accept his position unquestioningly. “There is a detail, hitherto unrevealed, which disposes of all such amiable suggestions,” she replied. “After the name referred to, someone in authority had inscribed the undeniable comment ‘As usual.’”

“The omen is a most encouraging one,” exclaimed Hien, throwing aside all his dejection. “Hitherto this person’s untiring efforts had met with no official recognition whatever. It is now obvious that far from being lost in the crowd he is becoming an object of honourable interest to the examiners.”

“One frequently hears it said, ‘After being struck on the head with an axe it is a positive pleasure to be beaten about the body with a wooden club,’” said Fa Fei, “and the meaning of the formerly elusive proverb is now explained. Would it not be prudent to avail yourself at length of the admittedly outrageous Tsin Lung’s services, so that this period of unworthy trial may be brought to a distinguished close?”

“It is said, ‘Do not eat the fruit of the stricken branch,’” replied Hien, “and this person will never owe his success to one who is so detestable in his life and morals that with every facility for a scholarly and contemplative existence he freely announces his barbarous intention of becoming a pirate. Truly the Dragon of Justice does but sleep for a little time, and when he awakens all that will be left of the mercenary Tsin Lung and those who associate with him will scarcely be enough to fill an orange skin.”

“Doubtless it will be so,” agreed Fa Fei, regretting, however, that Hien had not been content to prophesy a more limited act of vengeance, until, at least, her father had come to a definite decision regarding her own future. “Alas, though, the Book of Dynasties expressly says, ‘The one-legged never stumble,’ and Tsin Lung is so morally ill-balanced that the proverb may even apply to him.”

“Do not fear,” said Hien. “It is elsewhere written, ‘Love and leprosy few escape,’ and the spirit of Tsin Lung’s destiny is perhaps even at this moment lurking unsuspected behind some secret place.”

“If,” exclaimed a familiar voice, “the secret place alluded to should chance to be a hollow cedar-tree of inadequate girth, the unfortunate spirit in question will have my concentrated sympathy.”

“Just and magnanimous father!” exclaimed Fa Fei, thinking it more prudent not to recognize that he had learned of their meeting-place and concealing himself there had awaited their coming, “when your absence was discovered a heaven-sent inspiration led me to this spot. Have I indeed been permitted here to find you?”

“Assuredly you have,” replied Thang-li, who was equally desirous of concealing the real circumstances, although the difficulty of the position into which he had hastily and incautiously thrust his body on their approach compelled him to reveal himself. “The same inspiration led me to lose myself in this secluded spot, as being the one which you would inevitably search.”

“Yet by what incredible perversity does it arise, venerable Thang-li, that a leisurely and philosophical stroll should result in a person of your dignified proportions occupying so unattractive a position?” said Hien, who appeared to be too ingenuous to suspect Thang-li’s craft, in spite of a warning glance from Fa Fei’s expressive eyes.

“The remark is a natural one, O estimable youth,” replied Thang-li, doubtless smiling benevolently, although nothing of his person could be actually seen by Hien or Fa Fei, “but the recital is not devoid of humiliation. While peacefully studying the position of the heavens this person happened to glance into the upper branches of a tree and among them he beheld a bird’s nest of unusual size and richness—one that would promise to yield a dish of the rarest flavour. Lured on by the anticipation of so sumptuous a course, he rashly trusted his body to an unworthy branch, and the next moment, notwithstanding his unceasing protests to the protecting Powers, he was impetuously deposited within this hollow trunk.”

“Not unreasonably is it said, ‘A bird in the soup is better than an eagle’s nest in the desert,’” exclaimed Hien. “The pursuit of a fair and lofty object is set about with hidden pitfalls to others beyond you, O noble Chief Examiner! By what nimble-witted act of adroitness is it now your enlightened purpose to extricate yourself?”

At this admittedly polite but in no way inspiring question a silence of a very acute intensity seemed to fall on that part of the forest. The mild and inscrutable expression of Hien’s face did not vary, but into Fa Fei’s eyes there came an unexpected but not altogether disapproving radiance, while, without actually altering, the appearance of the tree encircling Thang-li’s form undoubtedly conveyed the impression that the benevolent smile which might hitherto have been reasonably assumed to exist within had been abruptly withdrawn.

“Your meaning is perhaps well-intentioned, gracious Hien,” said Thang-li at length, “but as an offer of disinterested assistance your words lack the gong-like clash of spontaneous enthusiasm. Nevertheless, if you will inconvenience yourself to the extent of climbing this not really difficult tree for a short distance you will be able to grasp some outlying portion of this one’s body without any excessive fatigue.”

“Mandarin,” replied Hien, “to touch even the extremity of your incomparable pig-tail would be an honour repaying all earthly fatigue—”

“Do not hesitate to seize it, then,” said Thang-li, as Hien paused. “Yet, if this person may without ostentation continue the analogy, to grasp him firmly by the shoulders must confer a higher distinction and would be even more agreeable to his own feelings.”

“The proposal is a flattering one,” continued Hien, “but my hands are bound down by the decree of the High Powers, for among the most inviolable of the edicts is it not written: ‘Do the lame offer to carry the footsore; the blind to protect the one-eyed? Distrust the threadbare person who from an upper back room invites you to join him in an infallible process of enrichment; turn aside from the one devoid of pig-tail who says, “Behold, a few drops daily at the hour of the morning sacrifice and your virtuous head shall be again like a well-sown rice-field at the time of harvest”; and towards the passing stranger who offers you that mark of confidence which your friends withhold close and yet again open a different eye. So shall you grow obese in wisdom’?”

“Alas!” exclaimed Thang-li, “the inconveniences of living in an Empire where a person has to regulate the affairs of his everyday life by the sacred but antiquated proverbial wisdom of his remote ancestors are by no means trivial. Cannot this possibly mythical obstacle be flattened-out by the amiable acceptance of a jar of sea snails or some other seasonable delicacy, honourable Hien?”

“Nothing but a really well-grounded encouragement as regards Fa Fei can persuade this person to regard himself as anything but a solitary outcast,” replied Hien, “and one paralysed in every useful impulse. Rather than abandon the opportunity of coming to such an arrangement he would almost be prepared to give up all idea of ever passing the examination for the second degree.”

“By no means,” exclaimed Thang-li hastily. “The sacrifice would be too excessive. Do not relinquish your sleuth-hound-like persistence, and success will inevitably reward your ultimate end.”

“Can it really be,” said Hien incredulously, “that my contemptible efforts are a matter of sympathetic interest to one so high up in every way as the renowned Chief Examiner?”

“They are indeed,” replied Thang-li, with that ingratiating candour that marked his whole existence. “Doubtless so prosaic a detail as the system of remuneration has never occupied your refined thoughts, but when it is understood that those in the position of this person are rewarded according to the success of the candidates you will begin to grasp the attitude.”

“In that case,” remarked Hien, with conscious humiliation, “nothing but a really sublime tolerance can have restrained you from upbraiding this obscure competitor as a thoroughly corrupt egg.”

“On the contrary,” replied Thang-li reassuringly, “I have long regarded you as the auriferous fowl itself. It is necessary to explain, perhaps, that the payment by result alluded to is not based on the number of successful candidates, but—much more reasonably as all those have to be provided with lucrative appointments by the authorities—on the economy effected to the State by those whom I can conscientiously reject. Owing to the malignant Tsin Lung’s sinister dexterity these form an ever-decreasing band, so that you may now be fittingly deemed the chief prop of a virtuous but poverty-afflicted line. When you reflect that for the past eleven years you have thus really had the honour of providing the engaging Fa Fei with all the necessities of her very ornamental existence you will see that you already possess practically all the advantages of matrimony. Nevertheless, if you will now bring our agreeable conversation to an end by releasing this inauspicious person he will consider the matter with the most indulgent sympathies.”

“Withhold!” exclaimed a harsh voice before Hien could reply, and from behind a tree where he had heard Thang-li’s impolite reference to himself Tsin Lung stood forth. “How does it chance, O two-complexioned Chief Examiner, that after weighing this one’s definite proposals—even to the extent of demanding a certain proportion in advance—you are now engaged in holding out the same alluring hope to another? Assuredly, if your existence is so critically imperilled this person and none other will release you and claim the reward.”

“Turn your face backwards, imperious Tsin Lung,” cried Hien. “These incapable hands alone shall have the overwhelming distinction of drawing forth the illustrious Thang-li.”

“Do not get entangled among my advancing footsteps, immature one,” contemptuously replied Tsin Lung, shaking the massive armour in which he was encased from head to foot. “It is inept for pigmies to stand before one who has every intention of becoming a rapacious pirate shortly.”

“The sedan-chair is certainly in need of new shafts,” retorted Hien, and drawing his sword with an expression of ferocity he caused it to whistle around his head so loudly that a flock of migratory doves began to arrive, under the impression that others of their tribe were calling them to assemble.

“Alas!” exclaimed Thang-li, in an accent of despair, “doubtless the wise Nung-yu was surrounded by disciples all eager that no other should succour him when he remarked: ‘A humble friend in the same village is better than sixteen influential brothers in the Royal Palace.’ In all this illimitable Empire is there not room for one whose aspirations are bounded by the submerged walls of a predatory junk and another whose occupation is limited to the upper passes of the Chunling mountains? Consider the poignant nature of this person’s vain regrets if by a couple of evilly directed blows you succeeded at this inopportune moment in exterminating one another!”

“Do not fear, exalted Thang-li,” cried Hien, who, being necessarily somewhat occupied in preparing himself against Tsin Lung’s attack, failed to interpret these words as anything but a direct encouragement to his own cause. “Before the polluting hands of one who disdains the Classics shall be laid upon your sacred extremities this tenacious person will fix upon his antagonist with a serpent-like embrace and, if necessary, suffer the spirits of both to Pass Upward in one breath.” And to impress Tsin Lung with his resolution he threw away his scabbard and picked it up again several times.

“Grow large in hope, worthy Chief Examiner,” cried Tsin Lung, who from a like cause was involved in a similar misapprehension. “Rather shall your imperishable bones adorn the interior of a hollow cedar-tree throughout all futurity than you shall suffer the indignity of being extricated by an earth-nurtured sleeve-snatcher.” And to intimidate Hien by the display he continued to clash his open hand against his leg armour until the pain became intolerable.

“Honourable warriors!” implored Thang-li in

Comments (0)