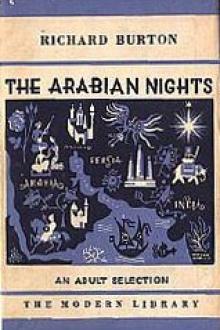

The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, vol 10 - Sir Richard Francis Burton (ebook reader with built in dictionary txt) 📗

- Author: Sir Richard Francis Burton

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, vol 10 - Sir Richard Francis Burton (ebook reader with built in dictionary txt) 📗». Author Sir Richard Francis Burton

“Let me not see his face,” cried the King, “but throw him into the mine.” This mine was eighty yards deep, and had not been opened for sixty years. It was closed by a heavy leaden cover, which they replaced, after they had loaded him with chains, and thrown him in. Saif sat there in the darkness, greatly troubled, and lamenting his condition to Him who never sleeps. Suddenly, a side wall of the mine opened, and a figure came forth which approached and called him by his name. “Who are you?” asked Saif.

“I am a woman named Akissa, and inhabit the mountain where the Nile rises. We are a nation who hold the faith of Abraham. A very pious man lives below us in a beautiful palace. But an evil Jinni named Mukhtatif lived near us also, who loved me, and demanded me in marriage of my father. He consented from fear, but I was unwilling to marry an evil being who was a worshipper of fire.

�How can you promise me in marriage to an infidel?’ said I to my father. �I shall thereby escape his malice myself,’ replied he. I went out and wept, and complained to the pious man about the affair. �Do you know who will kill him?’ said he to me, and I answered, �No.’ �I will direct you to him who has cut off his hand,’ said he. �His name is Saif Zul Yezn, and he is now in the city of King Kamrun, in the mine.’ Thereupon he brought me to you, and I come as you see me, to guide you to my country, that you may kill Mukhtatif, and free the earth from his wickedness.”

She then moved him, and shook him, and all his chains fell off.

She lifted him on her shoulders, and carried him to the palace of the Shaikh, who was named Abbas Salam. Here he heard a voice crying, “Enter, Saif Zul Yezn.” He did so, and found a grave and venerable old man, who gave him a very friendly reception, saying, “Wait till tomorrow, when Akissa will come to guide you to the castle of Mukhtatif.” He remained with him for the night, and when Akissa arrived next morning, the old man told her to hasten, that the world might be soon rid of the monster. They then left this venerable man, and when they had walked awhile, Akissa said to Saif, “Look before you.” He did so, and perceived a black mass at some distance. “This is the castle of the evil-doer,” said she, “but I cannot advance a step further than this.”

Saif therefore pursued his way alone, and when he came near the castle, he walked round it to look for the entrance. As he was noticing the extraordinary height of the castle, which was founded on the earth, but appeared to overtop the clouds, he saw a window open, and several people looked out, who pointed at him with their fingers, exclaiming, “That is he, that is he!” They threw him a rope, which they directed him to bind round him. They drew him up by it, when he found himself in the presence of three hundred and sixty damsels, who saluted him by his name.

*

(Here Habicht’s fragment ends.)

SCOTT’S MSS. AND TRANSLATIONS.

In 1800, Jonathan Scott, LL.D., published a volume of “Tales, Anecdotes, and Letters, translated from the Arabic and Persian,”

based upon a fragmentary MS., procured by J. Anderson in Bengal, which included the commencement of the work (Nos. 1-3) in 29

Nights; two tales not divided into Nights (Nos. 264 and 135) and No. 21.

Scott’s work includes these two new tales (since republished by Kirby and Clouston), with the addition of various anecedotes, &c., derived from other sources. The “Story of the Labourer and the Chair” has points of resemblance to that of “Malek and the Princess Chirine” (Shirin?) in the Thousand and One Days; and also to that of “Tuhfet El Culoub” (No. 183a) in the Breslau Edition. The additional tales in this MS. and vol. of translations are marked “A” under Scott in our Tables. Scott published the following specimens (text and translation) in Ouseley’s Oriental Collections (1797 and following years) No.

135m (i. pp. 245-257) and Introduction (ii. pp. 160-172; 228-257). The contents are fully given in Ouseley, vol. ii. pp. 34, 35.

Scott afterwards acquired an approximately complete MS. in 7

vols., written in 1764 which was brought from Turkey by E.

Wortley Montague. Scott published a table of contents (Ouseley, ii. pp. 25-34), in which, however, the titles of some few of the shorter tales, which he afterwards translated from it, are omitted, while the titles of others are differently translated.

Thus “Greece” of the Table becomes “Yemen” in the translation; and “labourer” becomes “sharper.” As a specimen, he subsequently printed the text and translation of No. 145 (Ouseley, ii. pp.

349-367).

This MS., which differs very much from all others known, is now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

In 1811, Scott published an edition of the Arabian Nights’

Entertainments, in 6 vols., vol. 1 containing a long introduction, and vol. 6, including a series of new tales from the Oxford MS. (There is a small paper edition; and also a large paper edition, the latter with frontispieces, and an Appendix including a table of the tales contained in the MS.) It had originally been Scott’s intention to retranslate the MS.; but he appears to have found it beyond his powers. He therefore contented himself with re-editing Galland, altering little except the spelling of the names, and saying that Galland’s version is in the main so correct that it would be useless repetition to go over the work afresh. Although he says that he found many of the tales both immoral and puerile, he translated most of those near the beginning, and omitted much more (including several harmless and interesting tales, such as No. 152) towards the end of his MS. than near the beginning. The greater part of Scott’s additional tales, published in vol. 6, are included in the composite French and German editions of Gauttier and Habicht; but, except Nos. 208, 209, and 215, republished in my “New Arabian Nights,” they have not been reprinted in England, being omitted in all the many popular versions which are professedly based upon Scott, even in the edition in 4 vols., published in 1882, which reprints Scott’s Preface.

The edition of 1882 was published about the same time as one of the latest reissues of Lane’s Thousand and One Nights; and the Saturday Review of Nov. 4, 1882 (p. 609), published an article on the Arabian Nights, containing the following amusing passage: “Then Jonathan Scott, LL.D. Oxon, assures the world that he intended to retranslate the tales given by Galland; but he found Galland so adequate on the whole that he gave up the idea, and now reprints Galland, with etchings by M. Lalauze, giving a French view of Arab life. Why Jonathan Scott, LL.D., should have thought to better Galland, while Mr. Lane’s version is in existence, and has just been reprinted, it is impossible to say.”

The most interesting of Scott’s additional tales, with reference to ordinary editions of The Nights, are as follows:—

No. 204b is a variant of No. 37.

No. 204c is a variant of 3e, in which the wife, instead of the husband, acts the part of a jealous tyrant. (Compare Cazotte’s story of Halechalbe.)

No. 204e. Here we have a reference to the Nesn�s, which only appears once in the ordinary versions of The Nights (No. 132b; Burton, v., p. 333).

No. 206b. is a variant of No. 156.

No. 207c. This relates to a bird similar to that in the Jealous Sisters (No. 198), and includes a variant of 3ba.

No. 207h. Another story of enchanted birds. The prince who seeks them encounters an “Oone” under similar circumstances to those under which Princess Parizade (No. 198) encounters the old durwesh. The description is hardly that of a Marid, with which I imagine the Ons are wrongly identified.

No. 208 contains the nucleus of the famous story of Aladdin (No.

193).

No. 209 is similar to No. 162; but we have again the well incident of No. 3ba, and the exposure of the children as in No.

198.

No. 215. Very similar to Hasan of Bassorah (No. 155). As Sir R.

F. Burton (vol. viii., p. 60, note) has called in question my identification of the Islands of W�kW�k with the Aru Islands near New Guinea, I will quote here the passages from Mr. A. R.

Wallace’s Malay Archipelago (chap. 31) on which I based it:—“The trees frequented by the birds are very lofty… . . One day I got under a tree where a number of the Great Paradise birds were assembled, but they were high up in the thickest of the foliage, and flying and jumping about so continually that I could get no good view of them… . . Their voice is most extraordinary. At early morn, before the sun has risen, we hear a loud cry of �Wawk—wawk—wawk, w k—w k—w k,’ which resounds through the forest, changing its direction continually. This is the Great Bird of Paradise going to seek his breakfast… . . The birds had now commenced what the people here call �sacaleli,’ or dancing-parties, in certain trees in the forest, which are not fruit-trees as I at first imagined, but which have an immense head of spreading branches and large but scattered leaves, giving a clear space for the birds to play and exhibit their plumes. On one of these trees a dozen or twenty full-plumaged male birds assemble together, raise up their wings, stretch out their necks, and elevate their exquisite plumes, keeping them in a continual vibration. Between whiles they fly across from branch to branch in great excitement, so that the whole tree is filled with waving plumes in every variety of attitude and motion.”

No. 216bc appears to

Comments (0)