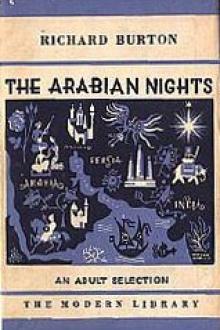

The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, vol 10 - Sir Richard Francis Burton (ebook reader with built in dictionary txt) 📗

- Author: Sir Richard Francis Burton

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, vol 10 - Sir Richard Francis Burton (ebook reader with built in dictionary txt) 📗». Author Sir Richard Francis Burton

[FN#265] For his poetry see Ibn Khallikan iv. 103.

[FN#266] Their flatterers compared them with the four elements.

[FN#267] Al-Mas’udi, chapt. cxii.

[FN#268] Ibn Khallikan (i. 310) says the eunuch Abu H�shim Masr�r, the Sworder of Vengeance, who is so pleasantly associated with Ja’afar in many nightly disguises; but the Eunuch survived the Caliph. Fakhr al-Din (p. 27) adds that Masrur was an enemy of Ja’afar; and gives further details concerning the execution.

[FN#269] Bresl. Edit., Night dlxvii. vol. vii. pp. 258-260; translated in the Mr. Payne’s “Tales from the Arabic,” vol. i.

189 and headed “Al-Rashid and the Barmecides.” It is far less lively and dramatic than the account of the same event given by Al-Mas’udi, chapt. cxii., by Ibn Khallikan and by Fakhr al-Din.

[FN#270] Al-Mas’udi, chapt. cxi.

[FN#271] See Dr. Jonathan Scott’s extracts from Major Ouseley’s “Tarikh-i-Barmaki.”

[FN#272] Al-Mas’udi, chapt. cxii. For the liberties Ja’afar took see Ibn Khallikan, i. 303.

[FN#273] Ibid. chapt. xxiv. In vol. ii. 29 of The Nights, I find signs of Ja’afar’s suspected heresy. For Al-Rashid’s hatred of the Zindiks see Al-Siyuti, pp. 292, 301; and as regards the religious troubles ibid. p. 362 and passim.

[FN#274] Biogr. Dict. i. 309.

[FN#275] This accomplished princess had a practice that suggests the Dame aux Cam�lias.

[FN#276] i. e. Perdition to your fathers, Allah’s curse on your ancestors.

[FN#277] See vol. iv. 159, “Ja’afar and the Beanseller;” where the great Wazir is said to have been “crucified;” and vol. iv.

pp. 179, 181. Also Roebuck’s Persian Proverbs, i. 2, 346, “This also is through the munificence of the Barmecides.”

[FN#278] I especially allude to my friend Mr. Payne’s admirably written account of it in his concluding Essay (vol. ix.). From his views of the Great Caliph and the Lady Zubaydah I must differ in every point except the destruction of the Barmecides.

[FN#279] Bresl. Edit., vol. vii. 261-62.

[FN#280] Mr. Grattan Geary, in a work previously noticed, informs us (i. 212) “The Sitt al-Zobeide, or the Lady Zobeide, was so named from the great Zobeide tribe of Arabs occupying the country East and West of the Euphrates near the Hindi’ah Canal; she was the daughter of a powerful Sheik of that Tribe.” Can this explain the “K�sim”?

[FN#281] Vol. viii. 296.

[FN#282] Burckhardt, “Travels in Arabia” vol. i. 185.

[FN#283] The reverse has been remarked by more than one writer; and contemporary French opinion seems to be that Victor Hugo’s influence on French prose, was on the whole, not beneficial.

[FN#284] Mr. W. S. Clouston, the “Storiologist,” who is preparing a work to be entitled “Popular Tales and Fictions; their Migrations and Transformations,” informs me the first to adapt this witty anecdote was Jacques de Vitry, the crusading bishop of Accon (Acre) who died at Rome in 1240, after setting the example of “Exempla” or instances in his sermons. He had probably heard it in Syria, and he changed the day-dreamers into a Milkmaid and her Milk-pail to suit his “flock.” It then appears as an “Exemplum” in the Liber de Donis or de Septem Donis (or De Dono Timoris from Fear the first gift) of Stephanus de Borbone, the Dominican, ob. Lyons, 1261: it treated of the gifts of the Holy Spirit (Isaiah xi. 2 and 3), Timor, Pietas, Scientia, Fortitudo, Consilium, Intellectus et Sapientia; and was plentifully garnished with narratives for the use of preachers.

[FN#285] The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register (new series, vol. xxx. Sept.-Dec. 1830, London, Allens, 1839); p. 69 Review of the Arabian Nights, the Mac. Edit. vol. i., and H. Torrens.

[FN#286] As a household edition of the “Arabian Nights” is now being prepared, the curious reader will have an opportunity of verifying this statement.

[FN#287] It has been pointed out to me that in vol. ii. p. 285, line 18 “Zahr Shah” is a mistake for Sulayman Shah.

[FN#288] I have lately found these lovers at Schloss Sternstein near Cilli in Styria, the property of my excellent colleague, Mr.

Consul Faber, dating from A. D. 1300 when Jobst of Reichenegg and Agnes of Sternstein were aided and abetted by a Capuchin of Seikkloster.

[FN#289] In page 226 Dr. Steingass sensibly proposes altering the last hemistich (lines 11-12) to

At one time showing the Moon and Sun.

[FN#290] Omitted by Lane for some reason unaccountable as usual.

A correspondent sends me his version of the lines which occur in The Nights (vol. v. 106 and 107):—

Behold the Pyramids and hear them teach What they can tell of Future and of Past: They would declare, had they the gift of speech, The deeds that Time hath wrought from first to last

My friends, and is there aught beneath the sky Can with th’ Egyptian Pyramids compare?

In fear of them strong Time hath passed by And everything dreads Time in earth and air.

[FN#291] A rhyming Romance by Henry of Waldeck (flor. A. D. 1160) with a Latin poem on the same subject by Odo and a prose version still popular in Germany. (Lane’s Nights iii. 81; and Weber’s “Northern Romances.”)

[FN#292] e. g. ‘Aj�ib al-Hind (= Marvels of Ind) ninth century, translated by J. Marcel Devic, Paris, 1878; and about the same date the Two Mohammedan Travellers, translated by Renaudot. In the eleventh century we have the famous Sayyid al-ldrisi, in the thirteenth the ‘Aj�ib al-Makhl�kat of Al-Kazwini and in the fourteenth the Khar�dat al-Aj�ib of Ibn Al-Wardi. Lane (in loco) traces most of Sindbad to the two latter sources.

[FN#293] So Hector France proposed to name his admirably realistic volume “Sous le Burnous” (Paris, Charpentier, 1886).

[FN#294] I mean in European literature, not in Arabic where it is a lieu commun. See three several forms of it in one page (505) of Ibn Kallikan, vol. iii.

[FN#295] My attention has been called to the resemblance between the half-lie and Job (i. 13-19).

[FN#296] Boccaccio (ob. Dec. 2, 1375), may easily have heard of The Thousand Nights and a Night or of its archetype the Haz�r Afs�nah. He was followed by the Piacevoli Notti of Giovan Francisco Straparola (A. D. 1550), translated into almost all European languages but English: the original Italian is now rare.

Then came the Heptameron ou Histoire des amans fortunez of Marguerite d’Angoul�me, Reyne de Navarre and only sister of Francis I. She died in 1549 before the days were finished: in 1558 Pierre Boaistuan published the Histoire des amans fortunez and in 1559 Claude Guiget the “Heptameron.” Next is the Hexameron of A. de Torquemada, Rouen, 1610; and, lastly, the Pentamerone or El Cunto de li Cunte of Giambattista Basile (Naples 1637), known by the meagre abstract of J. E. Taylor and the caricatures of George Cruikshank (London 1847-50). I propose to translate this Pentamerone direct from the Neapolitan and have already finished half the work.

[FN#297] Translated and well annotated by Prof. Tawney, who, however, affects asterisks and has considerably bowdlerised sundry of the tales, e. g. the Monkey who picked out the Wedge (vol. ii. 28). This tale, by the by, is found in the Khirad Afroz (i. 128) and in the Anwar-i-Suhayli (chapt. i.) and gave rise to the Persian proverb, “What has a monkey to do with carpentering?”

It is curious to compare the Hindu with the Arabic work whose resemblances are as remarkable as their differences, while even more notable is their correspondence in impressioning the reader.

The Thaumaturgy of both is the same: the Indian is profuse in demonology and witchcraft; in transformation and restoration; in monsters as wind-men, fire-men and water-men, in air-going elephants and flying horses (i. 541-43); in the wishing cow, divine goats and laughing fishes (i. 24); and in the speciosa miracula of magic weapons. He delights in fearful battles (i.

400) fought with the same weapons as the Moslem and rewards his heroes with a “turband of honour” (i. 266) in lieu of a robe.

There is a quaint family likeness arising from similar stages and states of society: the city is adorned for gladness, men carry money in a robe-corner and exclaim “Ha! good!” (for “Good, by Allah!”), lovers die with exemplary facility, the “soft-sided”

ladies drink spirits (i. 61) and princesses get drunk (i. 476); whilst the Eunuch, the Hetaira and the bawd (Kuttini) play the same preponderating parts as in The Nights. Our Brahman is strong in love-making; he complains of the pains of separation in this phenomenal universe; he revels in youth, “twin-brother to mirth,”

and beauty which has illuminating powers; he foully reviles old age and he alternately praises and abuses the sex, concerning which more presently. He delights in truisms, the fashion of contemporary Europe (see Palmerin of England chapt. vii), such as “It is the fashion of the heart to receive pleasure from those things which ought to give it,” etc. etc. What is there the wise cannot understand? and so forth. He is liberal in trite reflections and frigid conceits (i. 19, 55, 97, 103, 107, in fact everywhere); and his puns run through whole lines; this in fine Sanskrit style is inevitable. Yet some of his expressions are admirably terse and telling, e. g. Ascending the swing of Doubt: Bound together (lovers) by the leash of gazing: Two babes looking like Misery and Poverty: Old Age seized me by the chin: (A lake) first assay of the Creator’s skill: (A vow) difficult as standing on a sword-edge: My vital spirits boiled with the fire of woe: Transparent as a good man’s heart: There was a certain convent full of fools: Dazed with scripture-reading: The stones could not help laughing at him: The Moon kissed the laughing forehead of the East: She was like a wave of the Sea of Love’s insolence (ii.

127), a wave of the Sea of Beauty tossed up by the breeze of Youth: The King played dice, he loved slavegirls, he told lies, he sat up o’ nights, he waxed wroth without reason, he took wealth wrongously, he despised the good and honoured the bad (i.

562); with many choice bits of the same kind. Like the Arab the Indian is profuse in personification; but the doctrine of pre-existence, of incarnation and emanation and an excessive spiritualism ever aiming at the infinite, makes his imagery run mad. Thus we have Immoral Conduct embodied; the God of Death; Science; the Svarga-heaven; Evening; Untimeliness, and the Earth-bride, while the Ace and Deuce of dice are turned into a brace of Demons. There is also that grotesqueness which the French detect even in Shakespeare, e. g. She drank in his ambrosial form with thirsty eyes like partridges (i. 476) and it often results from the comparison of incompatibles, e. g. a row of birds likened to a garden of nymphs; and from forced allegories, the favourite figure of contemporary Europe. Again, the rhetorical Hindu style differs greatly from the sobriety, directness and simplicity of the Arab, whose motto is Brevity combined with precision, except where the latter falls into “fine writing.” And, finally, there is a something in the atmosphere of these Tales which is unfamiliar to the West and which makes them, as more than one has remarked to me, very hard reading.

[FN#298] The Introduction (i. 1-5) leads to the Curse of Pushpadanta and M�lyav�n who live on Earth as Varar�chi and Gun�dhya and this runs through lib. i. Lib. ii. begins with the Story of Ud�yana to whom we must be truly grateful as our only guide: he and his son Narav�hanadatta fill up the rest and end with lib. xviii. Thus

Comments (0)