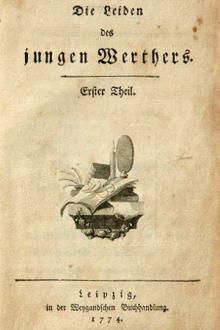

The Sorrows of Young Werther - Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (best ebook pdf reader android .txt) 📗

- Author: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Performer: -

Book online «The Sorrows of Young Werther - Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (best ebook pdf reader android .txt) 📗». Author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Adieu! I see no end to this wretchedness except the grave.

SEPTEMBER 3.

I must away. Thank you, Wilhelm, for determining my wavering purpose. For a whole fortnight I have thought of leaving her. I must away. She has returned to town, and is at the house of a friend. And then, Albert — yes, I must go.

SEPTEMBER 10.

Oh, what a night, Wilhelm! I can henceforth bear anything. I shall never see her again. Oh, why cannot I fall on your neck, and, with floods of tears and raptures, give utterance to all the passions which distract my heart! Here I sit gasping for breath, and struggling to compose myself. I wait for day, and at sunrise the horses are to be at the door.

And she is sleeping calmly, little suspecting that she has seen me for the last time. I am free. I have had the courage, in an interview of two hours’ duration, not to betray my intention. And O Wilhelm, what a conversation it was!

Albert had promised to come to Charlotte in the garden immediately after supper. I was upon the terrace under the tall chestnut trees, and watched the setting sun. I saw him sink for the last time beneath this delightful valley and silent stream. I had often visited the same spot with Charlotte, and witnessed that glorious sight; and now — I was walking up and down the very avenue which was so dear to me. A secret sympathy had frequently drawn me thither before I knew Charlotte; and we were delighted when, in our early acquaintance, we discovered that we each loved the same spot, which is indeed as romantic as any that ever captivated the fancy of an artist.

From beneath the chestnut trees, there is an extensive view. But I remember that I have mentioned all this in a former letter, and have described the tall mass of beech trees at the end, and how the avenue grows darker and darker as it winds its way among them, till it ends in a gloomy recess, which has all the charm of a mysterious solitude. I still remember the strange feeling of melancholy which came over me the first time I entered that dark retreat, at bright midday. I felt some secret foreboding that it would, one day, be to me the scene of some happiness or misery.

I had spent half an hour struggling between the contending thoughts of going and returning, when I heard them coming up the terrace.

I ran to meet them. I trembled as I took her hand, and kissed it.

As we reached the top of the terrace, the moon rose from behind the wooded hill. We conversed on many subjects, and, without perceiving it, approached the gloomy recess. Charlotte entered, and sat down. Albert seated himself beside her. I did the same, but my agitation did not suffer me to remain long seated. I got up, and stood before her, then walked backward and forward, and sat down again. I was restless and miserable. Charlotte drew our attention to the beautiful effect of the moonlight, which threw a silver hue over the terrace in front of us, beyond the beech trees.

It was a glorious sight, and was rendered more striking by the darkness which surrounded the spot where we were. We remained for some time silent, when Charlotte observed, “Whenever I walk by moonlight, it brings to my remembrance all my beloved and departed friends, and I am filled with thoughts of death and futurity. We shall live again, Werther!” she continued, with a firm but feeling voice; “but shall we know one another again what do you think?

what do you say?”

“Charlotte,” I said, as I took her hand in mine, and my eyes filled with tears, “we shall see each other again — here and hereafter we shall meet again.” I could say no more. Why, Wilhelm, should she put this question to me, just at the moment when the fear of our cruel separation filled my heart?

“And oh! do those departed ones know how we are employed here? do they know when we are well and happy? do they know when we recall their memories with the fondest love? In the silent hour of evening the shade of my mother hovers around me; when seated in the midst of my children, I see them assembled near me, as they used to assemble near her; and then I raise my anxious eyes to heaven, and wish she could look down upon us, and witness how I fulfil the promise I made to her in her last moments, to be a mother to her children. With what emotion do I then exclaim, ‘Pardon, dearest of mothers, pardon me, if I do not adequately supply your place! Alas! I do my utmost. They are clothed and fed; and, still better, they are loved and educated. Could you but see, sweet saint! the peace and harmony that dwells amongst us, you would glorify God with the warmest feelings of gratitude, to whom, in your last hour, you addressed such fervent prayers for our happiness.’” Thus did she express herself; but O Wilhelm! who can do justice to her language? how can cold and passionless words convey the heavenly expressions of the spirit? Albert interrupted her gently. “This affects you too deeply, my dear Charlotte. I know your soul dwells on such recollections with intense delight; but I implore — ” “O Albert!” she continued, “I am sure you do not forget the evenings when we three used to sit at the little round table, when papa was absent, and the little ones had retired.

You often had a good book with you, but seldom read it; the conversation of that noble being was preferable to everything, —

that beautiful, bright, gentle, and yet ever-toiling woman. God alone knows how I have supplicated with tears on my nightly couch, that I might be like her.”

I threw myself at her feet, and, seizing her hand, bedewed it with a thousand tears. “Charlotte!” I exclaimed, “God’s blessing and your mother’s spirit are upon you.” “Oh! that you had known her,”

she said, with a warm pressure of the hand. “She was worthy of being known to you.” I thought I should have fainted: never had I received praise so flattering. She continued, “And yet she was doomed to die in the flower of her youth, when her youngest child was scarcely six months old. Her illness was but short, but she was calm and resigned; and it was only for her children, especially the youngest, that she felt unhappy. When her end drew nigh, she bade me bring them to her. I obeyed. The younger ones knew nothing of their approaching loss, while the elder ones were quite overcome with grief. They stood around the bed; and she raised her feeble hands to heaven, and prayed over them; then, kissing them in turn, she dismissed them, and said to me, ‘Be you a mother to them.’ I gave her my hand. ‘You are promising much, my child,’ she said: ‘a mother’s fondness and a mother’s care! I have often witnessed, by your tears of gratitude, that you know what is a mother’s tenderness: show it to your brothers and sisters, and be dutiful and faithful to your father as a wife; you will be his comfort.’

She inquired for him. He had retired to conceal his intolerable anguish, — he was heartbroken, “Albert, you were in the room.

She heard some one moving: she inquired who it was, and desired you to approach. She surveyed us both with a look of composure and satisfaction, expressive of her conviction that we should be happy, — happy with one another.” Albert fell upon her neck, and kissed her, and exclaimed, “We are so, and we shall be so!” Even Albert, generally so tranquil, had quite lost his composure; and I was excited beyond expression.

“And such a being,” She continued, “was to leave us, Werther!

Great God, must we thus part with everything we hold dear in this world? Nobody felt this more acutely than the children: they cried and lamented for a long time afterward, complaining that men had carried away their dear mamma.”

Charlotte rose. It aroused me; but I continued sitting, and held her hand. “Let us go,” she said: “it grows late.” She attempted to withdraw her hand: I held it still. “We shall see each other again,” I exclaimed: “we shall recognise each other under every possible change! I am going,” I continued, “going willingly; but, should I say for ever, perhaps I may not keep my word. Adieu, Charlotte; adieu, Albert. We shall meet again.” “Yes: tomorrow, I think,” she answered with a smile. Tomorrow! how I felt the word!

Ah! she little thought, when she drew her hand away from mine.

They walked down the avenue. I stood gazing after them in the moonlight. I threw myself upon the ground, and wept: I then sprang up, and ran out upon the terrace, and saw, under the shade of the linden-trees, her white dress disappearing near the garden-gate.

I stretched out my arms, and she vanished.

BOOK II.

OCTOBER 20.

We arrived here yesterday. The ambassador is indisposed, and will not go out for some days. If he were less peevish and morose, all would be well. I see but too plainly that Heaven has destined me to severe trials; but courage! a light heart may bear anything.

A light heart! I smile to find such a word proceeding from my pen.

A little more lightheartedness would render me the happiest being under the sun. But must I despair of my talents and faculties, whilst others of far inferior abilities parade before me with the utmost self-satisfaction? Gracious Providence, to whom I owe all my powers, why didst thou not withhold some of those blessings I possess, and substitute in their place a feeling of self-confidence and contentment?

But patience! all will yet be well; for I assure you, my dear friend, you were right: since I have been obliged to associate continually with other people, and observe what they do, and how they employ themselves, I have become far better satisfied with myself. For we are so constituted by nature, that we are ever prone to compare ourselves with others; and our happiness or misery depends very much on the objects and persons around us. On this account, nothing is more dangerous than solitude: there our imagination, always disposed to rise, taking a new flight on the wings of fancy, pictures to us a chain of beings of whom we seem the most inferior. All things appear greater than they really are, and all seem superior to us. This operation of the mind is quite natural: we so continually feel our own imperfections, and fancy we perceive in others the qualities we do not possess, attributing to them also all that we enjoy ourselves, that by this process we form the idea of a perfect, happy man, — a man, however, who only exists in our own imagination.

But when, in spite of

Comments (0)