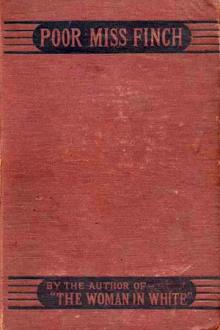

Poor Miss Finch - Wilkie Collins (best books to read for beginners txt) 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Book online «Poor Miss Finch - Wilkie Collins (best books to read for beginners txt) 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

One thing, at any rate, was plainly discernible in this otherwise inscrutable young man. He adored his twin-brother.

It would have been equally clear to me that Mr. Nugent Dubourg deserved to be worshipped, if I could have reconciled to my mind his leaving his brother to shift for himself in such a place as Dimchurch. I was obliged to remind myself of the admirable service which he had rendered at the trial, before I could decide to do him the justice of suspending my opinion of him, in his absence. Having accomplished this act of magnanimity, I took advantage of the first opportunity to change the subject. The most tiresome information that I am acquainted with, is the information which tells us of the virtues of an absent person—when that absent person happens to be a stranger.

“Is it true that you have taken Browndown for six months?” I asked. “Are you really going to settle at Dimchurch?”

“Yes—if you keep my secret,” he answered. “The people here know nothing about me. Don’t, pray don’t, tell them who I am! You will drive me away, if you do.”

“I must tell Miss Finch who you are,” I said.

“No! no! no!” he exclaimed eagerly. “I can’t bear the idea of her knowing it. I have been so horribly degraded. What will she think of me?” He burst into another explosion of rhapsodies on the subject of Lucilla—mixed up with renewed petitions to me to keep his story concealed from everybody. I lost all patience with his want of common fortitude and common sense.

“Young Oscar, I should like to box your ears!” I said. “You are in a villainously unwholesome state about this matter. Have you nothing else to think of? Have you no profession? Are you not obliged to work for your living?”

I spoke, as you perceive, with some force of expression—aided by a corresponding asperity of voice and manner.

Mr. Oscar Dubourg looked at me with the puzzled air of a man who feels an overflow of new ideas forcing itself into his mind. He modestly admitted the degrading truth. From his childhood upwards, he had only to put his hand in his pocket, and to find the money there, without any preliminary necessity of earning it first. His father had been a fashionable portrait-painter, and had married one of his sitters—an heiress. Oscar and Nugent had been left in the detestable position of independent gentlemen. The dignity of labor was a dignity unknown to these degraded young men. “I despise a wealthy idler,” I said to Oscar, with my republican severity. “You want the ennobling influence of labor to make a man of you. Nobody has a right to be idle—nobody has a right to be rich. You would be in a more wholesome state of mind about yourself, my young gentleman, if you had to earn your bread and cheese before you ate it.”

He stared at me piteously. The noble sentiments which I had inherited from Doctor Pratolungo, completely bewildered Mr. Oscar Dubourg.

“Don’t be angry with me,” he said, in his innocent way. “I couldn’t eat my cheese, if I did earn it. I can’t digest cheese. Besides, I employ myself as much as I can.” He took his little golden vase from the table behind him, and told me what I had already heard him tell Lucilla while I was listening at the window. “You would have found me at work this morning,” he went on, “if the stupid people who send me my metal plates had not made a mistake. The alloy, in the gold and silver both, is all wrong this time. I must return the plates to be melted again before I can do anything with them. They are all ready to go back to-day, when the cart comes. If there are any laboring people here who want money, I’m sure I will give them some of mine with the greatest pleasure. It isn’t my fault, ma’am, that my father married my mother. And how could I help it if he left two thousand a year each to my brother and me?”

Two thousand a year each to his brother and him! And the illustrious Pratolungo had never known what it was to have five pounds sterling at his disposal before his union with Me!

I lifted my eyes to the ceiling. In my righteous indignation, I forgot Lucilla and her curiosity about Oscar—I forgot Oscar and his horror of Lucilla discovering who he was. I opened my lips to speak. In another moment I should have launched my thunderbolts against the whole infamous system of modern society, when I was silenced by the most extraordinary and unexpected interruption that ever closed a woman’s lips.

THERE walked in, at the open door of the room—softly, suddenly, and composedly—a chubby female child, who could not possibly have been more than three years old. She had no hat or cap on her head. A dirty pinafore covered her from her chin to her feet. This amazing apparition advanced into the middle of the room, holding hugged under one arm a ragged and disreputable-looking doll; stared hard, first at Oscar, then at me; advanced to my knees; laid the disreputable doll on my lap; and, pointing to a vacant chair at my side, claimed the rights of hospitality in these words:

“Jicks will sit down.”

How was it possible, under these circumstances, to attack the infamous system of modern society? It was only possible to kiss “Jicks.”

“Do you know who this is?” I inquired, as I lifted our visitor on to the chair.

Oscar burst out laughing. Like me, he now saw this mysterious young lady for the first time. Like me, he wondered what the extraordinary nickname under which she had presented herself could possibly mean.

We looked at the child. The child—with its legs stretched out straight before it, terminating in a pair of little dusty boots with holes in them—lifted its large round eyes, overshadowed by a penthouse of unbrushed flaxen hair; looked gravely at us in return; and made a second call on our hospitality, as follows:

“Jicks will have something to drink.”

While Oscar ran into the kitchen for some milk, I succeeded in discovering the identity of “Jicks.”

Something—I cannot well explain what—in the manner in which the child had drifted into the room with her doll, reminded me of the lymphatic lady of the rectory, drifting backwards and forwards with the baby in one hand and the novel in the other. I took the liberty of examining “Jicks’s” pinafore, and discovered the mark in one corner:—“Selina Finch.” Exactly as I had supposed, here was a member of Mrs. Finch’s numerous family. Rather a young member, as it struck me, to be wandering hatless round the environs of Dimchurch, all by herself.

Oscar returned with the milk in a mug. The child—insisting on taking the mug into her own hands—steadily emptied it to the last drop—recovered her breath with a gasp—looked at me with a white mustache of milk on her upper lip—and announced the conclusion of her visit, in these terms:

“Jicks will get down again.”

I deposited our young friend on the floor. She took her doll, and stood for a moment deep in thought. What was she going to do next? We were not kept long in suspense. She suddenly put her little hot fat hand into mine, and tried to pull me after her out of the room.

“What do you want?” I asked.

Jicks answered in one untranslatable compound word:

“Man-Gee-gee.”

I suffered myself to be pulled out of the room—to see “Man-Gee-gee,” to play “Man-Gee-gee,” or to eat “Man-Gee-gee,” it was impossible to tell which. I was pulled along the passage—I was pulled out to the front door. There—having approached the house inaudibly to us, over the grass—stood the horse, cart, and man, waiting to take the case of gold and silver plates back to London. I looked at Oscar, who had followed me. We now understood, not only the masterly compound word of Jicks (signifying man and horse, and passing over cart as unimportant), but the polite attention of Jicks in entering the house to inform us, after a rest and a drink, of a circumstance which had escaped our notice. The driver of the cart had, on his own acknowledgment, been investigated and questioned by this extraordinary child; strolling up to the door of Browndown to see what he was doing there. Jicks was a public character at Dimchurch. The driver knew all about her. She had been nicknamed “Gipsy” from her wandering habits, and had shortened the name in her own dialect, into “Jicks.” There was no keeping her in at the rectory, try how you might: they had long since abandoned the effort in despair. Sooner or later, she turned up again—or somebody brought her back—or one of the sheep-dogs found her asleep under a bush, and gave the alarm. “What goes on in that child’s head,” said the driver, regarding Jicks with a sort of superstitious admiration, “the Lord only knows. She has a will of her own, and a way of her own. She is a child; and she aint a child. At three years of age, she’s a riddle none of us can guess. And that’s the long and the short of what I know about her.”

While this explanation was in progress, the carpenter who had nailed up the case, and the carpenter’s son, accompanying him, joined us in front of the house. They followed Oscar in, and came out again, bearing the heavy burden of precious metal—more than one man could conveniently lift—between them.

The case deposited in the cart, carpenter senior and carpenter junior got in after it, wanting “a lift” to Brighton.

Carpenter senior, a big burly man, made a joke. “It’s a lonely country between this and Brighton, sir,” he said to Oscar. Three of us will be none too many to see your precious packing-case safe into the railway station.” Oscar took it seriously. “Are there any robbers in this neighborhood?” he asked. “Lord love you, sir!” said the driver, “robbers would starve in these parts; we have got nothing worth thieving here.” Jicks—still watching the proceedings with an interest which allowed no detail to escape unnoticed—assumed the responsibility of starting the men on their journey. The odd child waved her chubby hand imperiously to her friend the driver, and cried in her loudest voice, “Away!” The driver touched his hat with comic respect. “All right, miss—time’s money, aint it?” He cracked his whip, and the cart rolled off noiselessly over the thick close turf of the South Downs.

It was time for me to go back to the rectory, and to restore the wandering Jicks, for the time being, to the protection of home. I returned to Oscar, to say goodbye.

“I wish I was going back with you,” he said.

“You will be as free as I am to come and to go at the rectory,” I answered, “when they know what has passed this morning between you and me. In your own interests, I am determined to tell them who you are. You have nothing to fear, and everything to gain, by my speaking out. Clear your mind of fancies and suspicions that are unworthy of you. By tomorrow we shall be good neighbors; by the end of the week we shall be good friends. For the present, as we say in France, au revoir!”

I turned to take Jicks

Comments (0)