Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗

- Author: Charles Dickens

Book online «Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗». Author Charles Dickens

‘Yes—yes,’ said Barnaby, with sparkling eyes. ‘To be sure I did! I told her so myself.’

‘I see,’ replied Lord George, with a reproachful glance at the unhappy mother. ‘I thought so. Follow me and this gentleman, and you shall have your wish.’

Barnaby kissed his mother tenderly on the cheek, and bidding her be of good cheer, for their fortunes were both made now, did as he was desired. She, poor woman, followed too—with how much fear and grief it would be hard to tell.

They passed quickly through the Bridge Road, where the shops were all shut up (for the passage of the great crowd and the expectation of their return had alarmed the tradesmen for their goods and windows), and where, in the upper stories, all the inhabitants were congregated, looking down into the street below, with faces variously expressive of alarm, of interest, expectancy, and indignation. Some of these applauded, and some hissed; but regardless of these interruptions—for the noise of a vast congregation of people at a little distance, sounded in his ears like the roaring of the sea—Lord George Gordon quickened his pace, and presently arrived before St George’s Fields.

They were really fields at that time, and of considerable extent. Here an immense multitude was collected, bearing flags of various kinds and sizes, but all of the same colour—blue, like the cockades—some sections marching to and fro in military array, and others drawn up in circles, squares, and lines. A large portion, both of the bodies which paraded the ground, and of those which remained stationary, were occupied in singing hymns or psalms. With whomsoever this originated, it was well done; for the sound of so many thousand voices in the air must have stirred the heart of any man within him, and could not fail to have a wonderful effect upon enthusiasts, however mistaken.

Scouts had been posted in advance of the great body, to give notice of their leader’s coming. These falling back, the word was quickly passed through the whole host, and for a short interval there ensued a profound and deathlike silence, during which the mass was so still and quiet, that the fluttering of a banner caught the eye, and became a circumstance of note. Then they burst into a tremendous shout, into another, and another; and the air seemed rent and shaken, as if by the discharge of cannon.

‘Gashford!’ cried Lord George, pressing his secretary’s arm tight within his own, and speaking with as much emotion in his voice, as in his altered face, ‘I am called indeed, now. I feel and know it. I am the leader of a host. If they summoned me at this moment with one voice to lead them on to death, I’d do it—Yes, and fall first myself!’

‘It is a proud sight,’ said the secretary. ‘It is a noble day for England, and for the great cause throughout the world. Such homage, my lord, as I, an humble but devoted man, can render—’

‘What are you doing?’ cried his master, catching him by both hands; for he had made a show of kneeling at his feet. ‘Do not unfit me, dear Gashford, for the solemn duty of this glorious day—’ the tears stood in the eyes of the poor gentleman as he said the words.—‘Let us go among them; we have to find a place in some division for this new recruit—give me your hand.’

Gashford slid his cold insidious palm into his master’s grasp, and so, hand in hand, and followed still by Barnaby and by his mother too, they mingled with the concourse.

They had by this time taken to their singing again, and as their leader passed between their ranks, they raised their voices to their utmost. Many of those who were banded together to support the religion of their country, even unto death, had never heard a hymn or psalm in all their lives. But these fellows having for the most part strong lungs, and being naturally fond of singing, chanted any ribaldry or nonsense that occurred to them, feeling pretty certain that it would not be detected in the general chorus, and not caring much if it were. Many of these voluntaries were sung under the very nose of Lord George Gordon, who, quite unconscious of their burden, passed on with his usual stiff and solemn deportment, very much edified and delighted by the pious conduct of his followers.

So they went on and on, up this line, down that, round the exterior of this circle, and on every side of that hollow square; and still there were lines, and squares, and circles out of number to review. The day being now intensely hot, and the sun striking down his fiercest rays upon the field, those who carried heavy banners began to grow faint and weary; most of the number assembled were fain to pull off their neckcloths, and throw their coats and waistcoats open; and some, towards the centre, quite overpowered by the excessive heat, which was of course rendered more unendurable by the multitude around them, lay down upon the grass, and offered all they had about them for a drink of water. Still, no man left the ground, not even of those who were so distressed; still Lord George, streaming from every pore, went on with Gashford; and still Barnaby and his mother followed close behind them.

They had arrived at the top of a long line of some eight hundred men in single file, and Lord George had turned his head to look back, when a loud cry of recognition—in that peculiar and half-stifled tone which a voice has, when it is raised in the open air and in the midst of a great concourse of persons—was heard, and a man stepped with a shout of laughter from the rank, and smote Barnaby on the shoulders with his heavy hand.

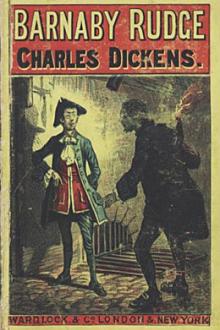

‘How now!’ he cried. ‘Barnaby Rudge! Why, where have you been hiding for these hundred years?’

Barnaby had been thinking within himself that the smell of the trodden grass brought back his old days at cricket, when he was a young boy and played on Chigwell Green. Confused by this sudden and boisterous address, he stared in a bewildered manner at the man, and could scarcely say ‘What! Hugh!’

‘Hugh!’ echoed the other; ‘ay, Hugh—Maypole Hugh! You remember my dog? He’s alive now, and will know you, I warrant. What, you wear the colour, do you? Well done! Ha ha ha!’

‘You know this young man, I see,’ said Lord George.

‘Know him, my lord! as well as I know my own right hand. My captain knows him. We all know him.’

‘Will you take him into your division?’

‘It hasn’t in it a better, nor a nimbler, nor a more active man, than Barnaby Rudge,’ said Hugh. ‘Show me the man who says it has! Fall in, Barnaby. He shall march, my lord, between me and Dennis; and he shall carry,’ he added, taking a flag from the hand of a tired man who tendered it, ‘the gayest silken streamer in this valiant army.’

‘In the name of God, no!’ shrieked the widow, darting forward. ‘Barnaby—my lord—see—he’ll come back—Barnaby—Barnaby!’

‘Women in the field!’ cried Hugh, stepping between them, and holding her off. ‘Holloa! My captain there!’

‘What’s the matter here?’ cried Simon Tappertit, bustling up in a great heat. ‘Do you call this order?’

‘Nothing like it, captain,’ answered Hugh, still holding her back

Comments (0)