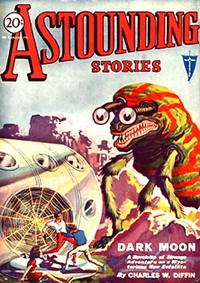

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 by Various (the gingerbread man read aloud txt) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories, August, 1931 by Various (the gingerbread man read aloud txt) 📗». Author Various

think we do not need you any more," he said at last. "I think, Herr Harkness, this is the end of our little argument—and, Herr Harkness, you lose. Now, I will tell you how it iss that you pay.

"You haff thought, perhaps, I would kill you. But you were wrong, as you many times have been. You haff not appreciated my kindness; you haff not understood that mine iss a heart of gold.

"Even I was not sure before we came what it iss best to do. But now I know. I saw oceans and many lands on this world. I saw islands in those oceans.

"You so clever are—such a great thinker iss Herr Harkness—and on one of those islands you will haff plenty of time to think—yess! You can think of your goot friend, Schwartzmann and of his kindness to you."

"You are going to maroon us on an island?" asked Walt Harkness hoarsely. Plainly his plans for seizing the ship were going awry. "You are going to put the three of us off in some lost corner of this world?"

Chet Bullard was silent until he saw the figure of Harkness struggling to throw off his two guards. "Walt," he called loudly, "take it easy! For God's sake, Walt, keep your head!"

This, Chet sensed, was no time for resistance. Let Schwartzmann go ahead with his plans; let him think them complacent and unresisting; let Max pilot the ship; then watch for an opening when they could land a blow that would count! He heard Schwartzmann laughing now, laughing as if he were enjoying something more pleasing than the struggles of Walt.

het was standing by the controls. The metal instrument-table was beside him; above it was the control itself, a metal ball that hung suspended in air within a cage of curved bars.

It was pure magic, this ball-control, where magnetic fields crossed and recrossed; it was as if the one who held it were a genie who could throw the ship itself where he willed. Glass almost enclosed the cage of bars, and the whole instrument swung with the self-compensating platform that adjusted itself to the "gravitation" of accelerated speed. The pilot, Max, had moved across to the instrument-table, ready for the take-off.

Schwartzmann's laughter died to a gurgling chuckle. He wiped his eyes before he replied to Harkness' question.

"Leave you," he said, "in one place? Nein! One here, the other there. A thousand miles apart, it might be. And not all three of you. That would be so unkind—"[196]

He interrupted himself to call to Kreiss who was opening the port.

"No," he ordered; "keep it closed. We are not going outside; we are going up."

But Kreiss had the port open. "I want a man to get some fresh water," he said; "he will only be a minute."

He shoved at a waiting man to hurry him through the doorway. It was only a gentle push; Chet wondered as he saw the man stagger and grasp at his throat. He was coughing—choking horribly for an instant outside the open port—then fell to the ground, while his legs jerked awkwardly, spasmodically.

Chet saw Kreiss follow. The scientist would have leaped to the side of the stricken man, whose body was so still now on the sunlit rock; but he, too, crumpled, then staggered back into the room. He pushed feebly at the port and swung it shut. His face, as he turned, was drawn into fearful lines.

"Acid!" He choked out the words between strangled breaths. "Acid—sulfuric—fumes!"

het turned quickly to the spectro-analyzer; the lines of oxygen and nitrogen were merged with others, and that meant an atmosphere unfit for human lungs! There had been a fumerole where yellowish vapor was spouting; he remembered it now.

"So!" boomed Schwartzmann, and now his squinting eyes were full on Chet. "You—you schwein! You said when we opened the ports there would be a surprise! Und this iss it! You thought to see us kill ourselves!"

"Open the port!" he shouted. The men who held Chet released him and sprang forward to obey. The pilot, Max, took their place. He put one hand on Chet's shoulder, while his other hand brought up a threatening, metal bar.

Schwartzmann's heavy face had lost its stolid look; it was alive with rage. He thrust his head forward to glare at the men, while he stood firmly, his feet far apart, two heavy fists on his hips. He whirled abruptly and caught Diane by one arm. He pulled her roughly to him and encircled the girl's trim figure with one huge arm.

"Put you all on one island?" he shouted. "Did you think I would put you all out of the ship? You"—he pointed at Harkness—"and you"—this time it was Chet—"go out now. You can die in your damned gas that you expected would kill me! But, you fools, you imbeciles—Mam'selle, she stays with me!" The struggling girl was helpless in the great arm that drew her close.

Harkness' mad rage gave place to a dead stillness. From bloodless lips in a chalk-white face he spat out one sentence:

"Take your filthy hands off her—now—or I'll—"

Schwartzmann's one free hand still held the pistol. He raised it with deadly deliberation; it came level with Harkness' unflinching eyes.

"Yes?" said Schwartzmann. "You will do—what?"

het saw the deadly tableau. He knew with a conviction that gripped his heart that here was the end. Walt would die and he would be next. Diane would be left defenseless.... The flashing thought that followed came to him as sharply as the crack of any pistol. It seemed to burst inside his brain, to lift him with some dynamic power of its own and project him into action.

He threw himself sideways from under the pilot's hand, out from beneath the heavy metal bar—and he whirled, as he leaped, to face the man. One lean, brown hand clenched to a fist that started a[197] long swing from somewhere near his knees; it shot upward to crash beneath the pilot's out-thrust jaw and lift him from the floor. Max had aimed the bar in a downward sweep where Chet's head had been the moment before; and now man and bar went down together. In the same instant Chet threw himself upon the weapon and leaped backward to his feet.

One frozen second, while, to Chet, the figures seemed as motionless as if carved from stone—two men beside the half-opened port—Harkness in convulsive writhing between two others—the figure of Diane, strained, tense and helpless in Schwartzmann's grasp—and Schwartzmann, whose aim had been disturbed, steadying the pistol deliberately upon Harkness—

"Wait!" Chet's voice tore through the confusion. He knew he must grip Schwartzmann's attention—hold that trigger finger that was tensed to send a detonite bullet on its way. "Wait, damn you! I'll answer your question. I'll tell you what we'll do!"

In that second he had swung the metal bar high; now he brought it crashing down in front of him. Schwartzmann flinched, half turned as if to fire at Chet, and saw the blow was not for him.

With a splintering crash, the bar went through an obstruction. There was sound of glass that slivered to a million mangled bits—the sharp tang of metal broken off—a crash and clatter—then silence, save for one bit of glass that fell belatedly to the floor, its tiny jingling crash ringing loud in the deathly stillness of the room....

It had been the control-room, this place of metal walls and of shining, polished instruments, and it could be called that no longer. For, battered to useless wreckage, there lay on a metal table a cage that had once been formed of curving bars. Among the fragments a metal ball that had guided the great ship still rocked idly from its fall, until it, too, was still.

It was a room where nothing moved—where no person so much as breathed....

Then came the Master Pilot's voice, and it was speaking with quiet finality.

"And that," he said, "is your answer. Our ship has made its last flight."

His eyes held steadily upon the blanched face of Herr Schwartzmann, whose limp arms released the body of Diane; the pistol hung weakly at the man's side. And the pilot's voice went on, so quiet, so hushed—so curiously toneless in that silent room.

"What was it that you said?—that Harkness and I would be staying here? Well, you were right when you said that, Schwartzmann; but it's a hard sentence, that—imprisonment for life."

Chet paused now, to smile deliberately, grimly at the dark face so bleached and bloodless, before he repeated:

"Imprisonment for life!—and you didn't know that you were sentencing yourself. For you're staying too, Schwartzmann, you contemptible, thieving dog! You're staying with us—here—on the Dark Moon!"

(To be continued.)

[198]

If The Sun Died By R. F. Starzl

y our system of time we would have called it around 65,000 A. D., but in this cavern world, miles below the long-forgotten surface of the earth, it was 49,889. Since the Death of the Sun. That legendary sun was but a dim racial memory, but the 24-hour day, based on its illusory travel across the sky, was still maintained by uranium clocks, by which the myriads who dwelt in the galleries and maze of the under-world warrens regulated their lives.

In the office of the nation's central electro-plant[199] sat a young man. He was unoccupied at the moment. He was an example of the marvelously slow process of evolution, for, to all outward appearances he differed little from a Twentieth Century man. Keen intelligence sat on his fine-cut, kindly young face. In general build he was lighter, more refined than a man of the past. Yet even the long, delicately colored robe of mineral silk which he wore could not detract from his obvious virility and strength.

His face flashed in a smile when a girl suddenly appeared in the middle of the room, materializing, so it seemed, out of nowhere. She resembled him to some extent, except that she was exquisitely feminine, dark-haired, with a skin of warm ivory, while he was blond and ruddy. Her tinkling, silvery voice was troubled as she asked:

"Have I your leave to stay, Mich'l Ares?"

The look of adoration he gave her was answer enough, but he answered with the conventional formula, "It is given." He rose to his feet, walked right through the seemingly solid vision and made an adjustment on a bank of dials. Then he walked through the apparition again and, standing beside his chair, looked at her inquiringly.

"You haven't forgotten, Mich'l, this is the day of the Referendum?"

Mich'l smiled slightly. It would be a day of confusion in Subterranea if he should forget. As chief of the technies he was in direct charge of the tabulating machines that would, a few seconds after the vote, give the result in the matter of the opening of the Frozen Gate. But the girl's concern sobered him instantly. On the decision of the people at noon depended the life work of her father, Senator Mane. And it was now nine o'clock.

"I am sure they will order the Gate opened," he said instantly. "All the technies are agreed that your father is right, that the Great Cold was only another, more severe ice age—not the death of the Sun. The technies—"

ust as the girl had seemingly materialized, a young man now stood beside her. In appearance he was a picture of pride, power, arrogance, and definite danger. His hawk-like, patrician features were smiling. This olive-skinned, dark young rival of Mich'l was Lane Mollon, son of Senator Mollon, ruthless administration leader and bitter opponent of Senator Mane's Exodus faction.

Lane looked at Mich'l insolently.

"Have I your leave to stay, Mich'l Ares?" he asked.

"It is given," said Mich'l without enthusiasm.

"I'm not calling on you of my own will, Mich'l," the apparition of young Mollon said

Comments (0)