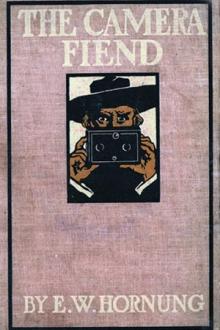

The Camera Fiend - E. W. Hornung (books you need to read txt) 📗

- Author: E. W. Hornung

- Performer: -

Book online «The Camera Fiend - E. W. Hornung (books you need to read txt) 📗». Author E. W. Hornung

“But not the whole truth, eh, Mullins! What about the little souvenirs you showed me yesterday?”

“There was no call to name them either, sir. The cheroot-end I must have picked up a hundred yards away, and even the medicine-cork wasn't on the actual scene of the murder.”

“That's all right, Mullins. I don't see what they could possibly have to do with it, myself; and really, but for the fluke of your being the one to find the body, and picking the first-fruits for what they're worth, it's the last kind of case that I should dream of touching with a ten-foot pole. By the way, I suppose they won't require you at the adjourned inquest?”

“They may not require me, sir, but I should like to attend, if quite convenient,” replied Mullins deferentially. “The police were very stingy with their evidence to-day; they've still to produce the fatal bullet, and I should like a sight of that, sir.”

Mr. Thrush did not continue the conversation, possibly because he took as little real interest as he professed in the case which was being thrust upon him, but more obviously owing to the necessary care in shaving the corners of a delightfuly long and mobile mouth. Indeed, the whole face emerging from the lather, as a cast from its clay, would have [pg 108] delighted any eye but its own. It was fat and flabby as the rest of Eugene Thrush; there was quite a collection of chins to shave; and yet anybody but himself must have recognised the invincible freshness of complexion, the happy penetration of every glance, as an earnest of inexhaustible possibilities beneath the burden of the flesh. Great round spectacles, through which he stared like a wise fish in an aquarium, were caught precariously on a button of a nose which in itself might have prevented the superficial observer from taking him any more seriously than he took himself.

Mr. Upton, who arrived before Thrush was visible, was an essentially superficial and antipathetic observer of unfamiliar types; and being badly impressed by the forbidding staircase, he had determined on the landing to sound his man before trusting him. In the rank undergrowth of his prejudices there was no more luxuriant weed than an innate abhorrence of London and all Londoners, which neither the cause of his visit nor the murky mien of Mullins was calculated to abate. The library of books in solid bindings, many of them legal tomes, was the first reassuring feature; another was the large desk, made business-like with pigeon-holes and a telephone; but Mr. Upton was only beginning to recover confidence when Eugene Thrush shook it sadly at his first entry.

[pg 109]It might have been by his face, or his fat, or his evening clothes seen from the motorist's dusty tweeds, almost as much as by the misplaced joviality with which Thrush exclaimed: “I'm sorry to have kept you waiting, sir, and the worst of it is that I can't let you keep me!”

This touched a raw nerve in the ironmaster, as the kind of reception one had to come up to London to incur. “Then I'll clear out!” said he, and would have been as good as his word but for its instantaneous effect.

Thrush had pulled out a gold watch after a stare of kindly consternation.

“I really am rather rushed,” said he; “but I can give you four minutes, if that's any good to you.”

Now, at first sight, before a word was spoken, Mr. Upton would have said four hours or four days of that boiled salmon in spectacles would have been no good to him; but the precise term of minutes, together with a seemlier but not less decisive manner, had already quickened the business man's respect for another whose time was valuable. This is by no means to say that Thrush had won him over in a breath. But the following interchange took place rapidly.

“I understand you're a detective, Mr. Thrush?”

“Hardly that, Mr.——I've left your card in the other room.”

[pg 110]“Upton is my name, sir.”

“I don't aspire to the official designation, Mr. Upton, an inquiry agent is all I presume to call myself.”

“But you do inquire into mysteries?”

“I've dabbled in them.”

“As an amateur?”

“A paid amateur, I fear.”

“I come on a serious matter, Mr. Thrush—a very serious matter to me!”

“Pardon me if I seem anything else for a moment; as it happens, you catch me dabbling, or rather meddling, in a serious case which is none of my business, but strictly a matter for the police, only it happens to have come my way by a fluke. I am not a policeman, but a private inquisitor. If you want anything or anybody ferreted out, that's my job and I should put it first.”

“Mr. Thrush, that's exactly what I do want, if only you can do it for me! I had reason to fear, from what I heard this morning, that my youngest child, a boy of sixteen, had disappeared up here in London, or been decoyed away. And now there can be no doubt about it!”

So, in about one of the allotted minutes, Thrush was trusted on grounds which Mr. Upton could not easily have explained; but the time was up before he had concluded a briefly circumstantial report of the facts within his knowledge.

[pg 111]“When can I see you again?” he asked abruptly of Thrush.

“When? What do you mean, Mr. Upton?”

“The four minutes must be more than up.”

“Go on, my dear sir, and don't throw good time after bad. I'm only dining with a man at his club. He can wait.”

“Thank you, Mr. Thrush.”

“More good time! How do you know the boy hasn't turned up at school or at home while you've been fizzing in a cloud of dust?”

“I was to have a wire at the hotel I always stop at; there's nothing there; but the first thing they told me was that my boy had been for a bed which they couldn't give him the night before last. I did let them have it! But it seems the manager was out, and his understrappers had recommended other hotels; they've just been telephoning to them all in turn, but at every one the poor boy seems to have fared the same. Then I've been in communication with these infernal people in St. John's Wood, and with the doctor, but none of them have heard anything. I thought I'd like to do what I could before coming to you, Mr. Thrush, but that's all I've done or know how to do. Something must have happened!”

“It begins to sound like it,” said Thrush gravely.

[pg 112]“But there are happenings and happenings; it may be only a minor accident. One moment!”

And he returned to the powder-closet of its modish day, where Mullins was still pursuing his ostensibly menial avocation. What the master said was inaudible in the library, but the man hurried out in front of him, and was heard clattering down the evil stairs next minute.

“In less than an hour,” explained Thrush, “he will be back with a list of the admissions at the principal hospitals for the last forty-eight hours. I don't say there's much in it; your boy had probably some letter or other means of easier indentification about him; but it's worth trying.”

“It is, indeed!” murmured Mr. Upton, much impressed.

“And while he is trying it,” exclaimed Eugene Thrush, lighting up as with a really great idea, “you'll greatly oblige me by having a whisky-and-soda in the first place.”

“No, thank you! I haven't had a bite all day. It would fly to my head.”

“But that's its job; that's where it's meant to fly,” explained the convivial Mr. Thrush, preparing the potion with practised hand. Baited with a biscuit it was eventually swallowed, and a flagging giant refreshed by his surrender. It made [pg 113] him like his new acquaintance too well to bear the thought of detaining him any more.

“Go to your dinner, man, and let me waylay you later!”

“Thank you, I prefer to keep you now I've got you, Mr. Upton! My man begins his round by going to tell my pal I can't dine with him at all. Not a word, I beg! I'll have a bite with you instead when Mullins gets back, and in a taxi that won't be long.”

“But do you think you can do anything?”

The question floated in pathetic evidence on a flood of inarticulate thanks.

“If you give me time, I hope so,” was the measured answer. “But the needle in the hay is nothing to the lost unit in London, and it will take time. I'm not a magazine detective, Mr. Upton; if you want a sixpenny solution for soft problems, don't come to me!”

At an earlier stage the ironmaster would have raised his voice and repeated that this was a serious matter; even now he looked rather reproachfully at Eugene Thrush, who came back to business on the spot.

“I haven't asked you for a description of the boy, Mr. Upton, because it's not much good if we've got to keep the matter to ourselves. But is there anything distinctive about him besides the asthma?”

“Nothing; he was never an athlete, like my other boys.”

[pg 114]“Come! I call that a distinction in itself,” said Mr. Thrush, smiling down his own unathletic waistcoat. “But as a matter of fact, nothing could be better than the very complaint which no doubt unfits him for games.”

“Nothing better, do you say?”

“Emphatically, from my point of view. It's harder to hide a man's asthma than to hide the man himself.”

“I never thought of that.”

It was impossible to tell whether Thrush had thought of it before that moment. The round glasses were levelled at Mr. Upton with an inscrutable stare of the marine eyes behind them.

“I suppose it has never affected his heart?” he inquired nonchalantly; but the nonchalance was a thought too deliberate for paternal perceptions quickened as were those of Mr. Upton.

“Is that why you sent round the hospitals, Mr. Thrush?”

“It was one reason, but honestly not the chief.”

“I certainly never thought of his heart!”

“Nor do I think you need now, in the case of so young a boy,” said Thrush

Comments (0)