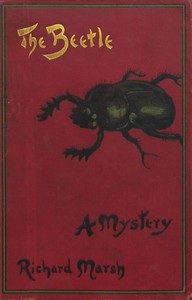

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗». Author Richard Marsh

‘In—in the very act of dying.’

‘In the very act of dying?’

‘If—he had seen a follower of Isis in—the very act of dying, assume—the form of a—a beetle, on any conceivable grounds would such a transformation be susceptible of a natural explanation?’

I stared,—as who would not? Such an extraordinary question was rendered more extraordinary by coming from such a man,—yet I was almost beginning to suspect that there was something behind it more extraordinary still.

‘Look here, Lessingham, I can see you’ve a capital tale to tell,—so tell it, man! Unless I’m mistaken, it’s not the kind of tale in which ordinary scruples can have any part or parcel,—anyhow, it’s hardly fair of you to set my curiosity all agog, and then to leave it unappeased.’

He eyed me steadily, the appearance of interest fading more and more, until, presently, his face assumed its wonted expressionless mask,—somehow I was conscious that what he had seen in my face was not altogether to his liking. His voice was once more bland and self-contained.

‘I perceive you are of opinion that I have been told a taradiddle. I suppose I have.’

‘But what is the taradiddle?—don’t you see I’m burning?’

‘Unfortunately, Atherton, I am on my honour. Until I have permission to unloose it, my tongue is tied.’ He picked up his hat and umbrella from where he had placed them on the table. Holding them in his left hand, he advanced to me with his right outstretched. ‘It is very good of you to suffer my continued interruption; I know, to my sorrow, what such interruptions mean,—believe me, I am not ungrateful. What is this?’

On the shelf, within a foot or so of where I stood, was a sheet of paper,—the size and shape of half a sheet of post note. At this he stooped to glance. As he did so, something surprising occurred. On the instant a look came on to his face which, literally, transfigured him. His hat and umbrella fell from his grasp on to the floor. He retreated, gibbering, his hands held out as if to ward something off from him, until he reached the wall on the other side of the room. A more amazing spectacle than he presented I never saw.

‘Lessingham!’ I exclaimed. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

My first impression was that he was struck by a fit of epilepsy,—though anyone less like an epileptic subject it would be hard to find. In my bewilderment I looked round to see what could be the immediate cause. My eye fell upon the sheet of paper. I stared at it with considerable surprise. I had not noticed it there previously, I had not put it there,—where had it come from? The curious thing was that, on it, produced apparently by some process of photogravure, was an illustration of a species of beetle with which I felt that I ought to be acquainted, and yet was not. It was of a dull golden green; the colour was so well brought out,—even to the extent of seeming to scintillate, and the whole thing was so dexterously done that the creature seemed alive. The semblance of reality was, indeed, so vivid that it needed a second glance to be assured that it was a mere trick of the reproducer. Its presence there was odd,—after what we had been talking about it might seem to need explanation; but it was absurd to suppose that that alone could have had such an effect on a man like Lessingham.

With the thing in my hand, I crossed to where he was,—pressing his back against the wall, he had shrunk lower inch by inch till he was actually crouching on his haunches.

‘Lessingham!—come, man, what’s wrong with you?’

Taking him by the shoulder, I shook him with some vigour. My touch had on him the effect of seeming to wake him out of a dream, of restoring him to consciousness as against the nightmare horrors with which he was struggling. He gazed up at me with that look of cunning on his face which one associates with abject terror.

‘Atherton?—Is it you?—It’s all right,—quite right.—I’m well,—very well.’

As he spoke, he slowly drew himself up, till he was standing erect.

‘Then, in that case, all I can say is that you have a queer way of being very well.’

He put his hand up to his mouth, as if to hide the trembling of his lips.

‘It’s the pressure of overwork,—I’ve had one or two attacks like this,—but it’s nothing, only—a local lesion.’

I observed him keenly; to my thinking there was something about him which was very odd indeed.

‘Only a local lesion!—If you take my strongly-urged advice you’ll get a medical opinion without delay,—if you haven’t been wise enough to have done so already.’

‘I’ll go to-day;—at once; but I know it’s only mental overstrain.’

‘You’re sure it’s nothing to do with this?’

I held out in front of him the photogravure of the beetle. As I did so he backed away from me, shrieking, trembling as with palsy.

‘Take it away! take it away!’ he screamed.

I stared at him, for some seconds, astonished into speechlessness. Then I found my tongue.

‘Lessingham!—It’s only a picture!—Are you stark mad?’

He persisted in his ejaculations.

‘Take it away! take it away!—Tear it up!—Burn it!’

His agitation was so unnatural,—from whatever cause it arose!—that, fearing the recurrence of the attack from which he had just recovered, I did as he bade me. I tore the sheet of paper into quarters, and, striking a match, set fire to each separate piece. He watched the process of incineration as if fascinated. When it was concluded, and nothing but ashes remained, he gave a gasp of relief.

‘Lessingham,’ I said, ‘you’re either mad already, or you’re going mad,—which is it?’

‘I think it’s neither. I believe I am as sane as you. It’s—it’s that story of which I was speaking; it—it seems curious, but I’ll tell you all about it—some day. As I observed, I think you will find it an interesting instance of a singular survival.’ He made an obvious effort to become more like his usual self. ‘It is extremely unfortunate, Atherton, that I should have troubled you with such a display of weakness,—especially as I am able to offer you so scant an explanation. One thing I would ask of you,—to observe strict confidence. What has taken place has been between ourselves. I am in your hands, but you are my friend, I know I can rely on you not to speak of it to anyone,—and, in particular, not to breathe a hint of it to Miss Lindon.’

‘Why, in particular, not to Miss Lindon?’

‘Can you not guess?’

I hunched my shoulder.

‘If what I guess is what you mean is not that a cause the more why silence would be unfair to her?’

‘It is for me to speak, if for anyone. I shall not fail to do what should be done.—Give me your promise that you will not hint a word to her of what you have so unfortunately seen?’

I gave him the promise he required.

* * * * * * *

There was no more work for me that day. The Apostle, his divagations, his example of the coleoptera, his Arabian friend,—these things were as microbes which, acting on a system already predisposed for their reception, produced high fever; I was in a fever,—of unrest. Brain in a whirl!—Marjorie, Paul, Isis, beetle, mesmerism, in delirious jumble. Love’s upsetting!—in itself a sufficiently severe disease; but when complications intervene, suggestive of mystery and novelties, so that you do not know if you are moving in an atmosphere of dreams or of frozen facts,—if, then, your temperature does not rise, like that rocket of M. Verne’s,—which reached the moon, then you are a freak of an entirely genuine kind, and if the surgeons do not preserve you, and place you on view, in pickle, they ought to, for the sake of historical doubters, for no one will believe that there ever was a man like you, unless you yourself are somewhere around to prove them Thomases.

Myself,—I am not that kind of man. When I get warm I grow heated, and when I am heated there is likely to be a variety show of a gaudy kind. When Paul had gone I tried to think things out, and if I had kept on trying something would have happened—so I went on the river instead.

CHAPTER XIV.THE DUCHESS’ BALL

That night was the Duchess of Datchet’s ball—the first person I saw as I entered the dancing-room was Dora Grayling.

I went straight up to her.

‘Miss Grayling, I behaved very badly to you last night, I have come to make to you my apologies,—to sue for your forgiveness!’

‘My forgiveness?’ Her head went back,—she has a pretty bird-like trick of cocking it a little on one side. ‘You were not well. Are you better?’

‘Quite.—You forgive me? Then grant me plenary absolution by giving me a dance for the one I lost last night.’

She rose. A man came up,—a stranger to me; she’s one of the best hunted women in England,—there’s a million with her.

‘This is my dance, Miss Grayling.’

She looked at him.

‘You must excuse me. I am afraid I have made a mistake. I had forgotten that I was already engaged.’

I had not thought her capable of it. She took my arm, and away we went, and left him staring.

‘It’s he who’s the sufferer now,’ I whispered, as we went round,—she can waltz!

‘You think so? It was I last night,—I did not mean, if I could help it, to suffer again. To me a dance with you means something.’ She went all red,—adding, as an afterthought, ‘Nowadays so few men really dance. I expect it’s because you dance so well.’

‘Thank you.’

We danced the waltz right through, then we went to an impromptu shelter which had been rigged up on a balcony. And we talked. There’s something sympathetic about Miss Grayling which leads one to talk about one’s self,—before I was half aware of it I was telling her of all my plans and projects,—actually telling her of my latest notion which, ultimately, was to result in the destruction of whole armies as by a flash of lightning. She took an amount of interest in it which was surprising.

‘What really stands in the way of things of this sort is not theory but practice,—one can prove one’s facts on paper, or on a small scale in a room; what is wanted is proof on a large scale, by actual experiment. If, for instance, I could take my plant to one of the forests of South America, where there is plenty of animal life but no human, I could demonstrate the soundness of my position then and there.’

‘Why don’t you?’

‘Think of the money it would cost.’

‘I thought I was a friend of yours.’

‘I had hoped you were.’

‘Then why don’t you let me help you?’

‘Help me?—How?’

‘By letting you have the money for your South American experiment;—it would be an investment on which I should expect to receive good interest.’

I fidgeted.

‘It is very good of you, Miss Grayling, to talk like that.’

She became quite frigid.

‘Please don’t be absurd!—I perceive quite clearly that you are snubbing me, and that you are trying to do it as delicately as you know how.’

‘Miss Grayling!’

‘I understand that it was an impertinence on my part to volunteer assistance which was unasked; you have made that sufficiently plain.’

‘I assure you—’

‘Pray don’t. Of course, if it had been Miss Lindon it would have been different; she would at least have received a civil answer. But we are not all Miss Lindon.’

I was aghast. The outburst was so uncalled for,—I had not the faintest notion what I had said or done to cause it; she was in such a surprising passion—and it suited her!—I thought I had never seen her look prettier,—I could do nothing else but stare. So she went on,—with just as little reason.

‘Here is someone coming to claim this dance,—I can’t throw all my partners over. Have I offended you so irremediably that it will be impossible for you to dance with me again?’

‘Miss Grayling!—I shall be only too delighted.’ She handed me her card. ‘Which may I have?’

‘For your own sake you had better place it as far off as you possibly can.’

‘They all seem taken.’

‘That doesn’t matter; strike off any name you please, anywhere and put your own instead.’

It was giving me an almost embarrassingly free hand. I booked myself for the next waltz but two,—who it was who would have to give way to me I did not trouble to inquire.

‘Mr Atherton!—Is that you?’

It was,—it was also she. It

Comments (0)