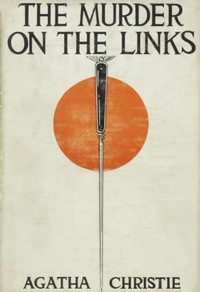

The Murder on the Links by Agatha Christie (100 best novels of all time .TXT) 📗

- Author: Agatha Christie

Book online «The Murder on the Links by Agatha Christie (100 best novels of all time .TXT) 📗». Author Agatha Christie

I was revolving sundry matters in my mind.

“But Mr. Renauld’s letter? It distinctly mentions a secret and Santiago?”

“Undoubtedly there was a secret in M. Renauld’s life—there can be no doubt of that. On the other hand, the word Santiago, to my mind, is a red herring, dragged continually across the track to put us off the scent. It is possible that it was used in the same way on M. Renauld, to keep him from directing his suspicions into a quarter nearer at hand. Oh, be assured, Hastings, the danger that threatened him was not in Santiago, it was near at hand, in France.”

He spoke so gravely, and with such assurance, that I could not fail to be convinced. But I essayed one final objection:

“And the match and cigarette end found near the body? What of them.”

A light of pure enjoyment lit up Poirot’s face.

“Planted! Deliberately planted there for Giraud or one of his tribe to find! Ah, he is smart, Giraud, he can do his tricks! So can a good retriever dog. He comes in so pleased with himself. For hours he has crawled on his stomach. ‘See what I have found,’ he says. And then again to me: ‘What do you see here?’ Me, I answer, with profound and deep truth, ‘Nothing.’ And Giraud, the great Giraud, he laughs, he thinks to himself, ‘Oh, that he is imbecile, this old one!’ But we shall see. …”

But my mind had reverted to the main facts.

“Then all this story of the masked men—?”

“Is false.”

“What really happened?”

Poirot shrugged his shoulders.

“One person could tell us—Madame Renauld. But she will not speak. Threats and entreaties would not move her. A remarkable woman that, Hastings. I recognized as soon as I saw her that I had to deal with a woman of unusual character. At first, as I told you, I was inclined to suspect her of being concerned in the crime. Afterwards I altered my opinion.”

“What made you do that?”

“Her spontaneous and genuine grief at the sight of her husband’s body. I could swear that the agony in that cry of hers was genuine.”

“Yes,” I said thoughtfully, “one cannot mistake these things.”

“I beg your pardon, my friend—one can always be mistaken. Regard a great actress, does not her acting of grief carry you away and impress you with its reality? No, however strong my own impression and belief, I needed other evidence before I allowed myself to be satisfied. The great criminal can be a great actor. I base my certainty in this case, not upon my own impression, but upon the undeniable fact that Mrs. Renauld actually fainted. I turned up her eyelids and felt her pulse. There was no deception—the swoon was genuine. Therefore I was satisfied that her anguish was real and not assumed. Besides, a small additional point not without interest, it was unnecessary for Mrs. Renauld to exhibit unrestrained grief. She had had one paroxysm on learning of her husband’s death, and there would be no need for her to simulate another such a violent one on beholding his body. No, Mrs. Renauld was not her husband’s murderess. But why has she lied? She lied about the wrist watch, she lied about the masked men—she lied about a third thing. Tell me, Hastings, what is your explanation of the open door?”

“Well,” I said, rather embarrassed, “I suppose it was an oversight. They forgot to shut it.”

Poirot shook his head, and sighed.

“That is the explanation of Giraud. It does not satisfy me. There is a meaning behind that open door which for a moment I cannot fathom.”

“I have an idea,” I cried suddenly.

“A la bonne heure! Let us hear it.”

“Listen. We are agreed that Mrs. Renauld’s story is a fabrication. Is it not possible, then, that Mr. Renauld left the house to keep an appointment—possibly with the murderer—leaving the front door open for his return. But he did not return, and the next morning he is found, stabbed in the back.”

“An admirable theory, Hastings, but for two facts which you have characteristically overlooked. In the first place, who gagged and bound Madame Renauld? And why on earth should they return to the house to do so? In the second place, no man on earth would go out to keep an appointment wearing his underclothes and an overcoat. There are circumstances in which a man might wear pajamas and an overcoat—but the other, never!”

“True,” I said, rather crest-fallen.

“No,” continued Poirot, “we must look elsewhere for a solution of the open door mystery. One thing I am fairly sure of—they did not leave through the door. They left by the window.”

“What?”

“Precisely.”

“But there were no footmarks in the flower bed underneath.”

“No—and there ought to have been. Listen, Hastings. The gardener, Auguste, as you heard him say, planted both those beds the preceding afternoon. In the one there are plentiful impressions of his big hobnailed boots—in the other, none! You see? Some one had passed that way, some one who, to obliterate their footprints, smoothed over the surface of the bed with a rake.”

“Where did they get a rake?”

“Where they got the spade and the gardening gloves,” said Poirot impatiently. “There is no difficulty about that.”

“What makes you think that they left that way, though? Surely it is more probable that they entered by the window, and left by the door.”

“That is possible of course. Yet I have a strong idea that they left by the window.”

“I think you are wrong.”

“Perhaps, mon ami.”

I mused, thinking over the new field of conjecture that Poirot’s deductions had opened up to me. I recalled my wonder at his cryptic allusions to the flower bed and the wrist watch. His remarks had seemed so meaningless at the moment and now, for the first time, I realized how remarkably, from a few slight incidents, he had unravelled much of the mystery that surrounded the case. I paid a belated homage to my friend. As though he read my thoughts, he nodded sagely.

“Method, you comprehend! Method! Arrange your facts. Arrange your ideas. And if some little fact will not fit in—do not reject it but consider it closely. Though its significance escapes you, be sure that it is significant.”

“In the meantime,” I said, considering, “although we know a great deal more than we did, we are no nearer to solving the mystery of who killed Mr. Renauld.”

“No,” said Poirot cheerfully. “In fact we are a great deal further off.”

The fact seemed to afford him such peculiar satisfaction that I gazed at him in wonder. He met my eye and smiled.

“But yes, it is better so. Before, there was at all events a clear theory as to how and by whose hands he met his death. Now that is all gone. We are in darkness. A hundred conflicting points confuse and worry us. That is well. That is excellent. Out of confusion comes forth order. But if you find order to start with, if a crime seems simple and above-board, eh bien, méfiez vous! It is, how do you say it?—cooked! The great criminal is simple—but very few criminals are great. In trying to cover up their tracks, they invariably betray themselves. Ah, mon ami, I would that some day I could meet a really great criminal—one who commits his crime, and then—does nothing! Even I, Hercule Poirot, might fail to catch such a one.”

But I had not followed his words. A light had burst upon me.

“Poirot! Mrs. Renauld! I see it now. She must be shielding somebody.”

From the quietness with which Poirot received my remark, I could see that the idea had already occurred to him.

“Yes,” he said thoughtfully. “Shielding some one—or screening some one. One of the two.”

I saw very little difference between the two words, but I developed my theme with a good deal of earnestness. Poirot maintained a strictly non-committal attitude, repeating:

“It may be—yes, it may be. But as yet I do not know! There is something very deep underneath all this. You will see. Something very deep.”

Then, as we entered our hotel, he enjoined silence on me with a gesture.

The Girl with the Anxious Eyes

We lunched with an excellent appetite. I understood well enough that Poirot did not wish to discuss the tragedy where we could so easily be overheard. But, as is usual when one topic fills the mind to the exclusion of everything else, no other subject of interest seemed to present itself. For a while we ate in silence, and then Poirot observed maliciously:

“Eh bien! And your indiscretions! You recount them not?”

I felt myself blushing.

“Oh, you mean this morning?” I endeavoured to adopt a tone of absolute nonchalance.

But I was no match for Poirot. In a very few minutes he had extracted the whole story from me, his eyes twinkling as he did so.

“Tiens! A story of the most romantic. What is her name, this charming young lady?”

I had to confess that I did not know.

“Still more romantic! The first rencontre in the train from Paris, the second here. Journeys end in lovers’ meetings, is not that the saying?”

“Don’t be an ass, Poirot.”

“Yesterday it was Mademoiselle Daubreuil, today it is Mademoiselle—Cinderella! Decidedly you have the heart of a Turk, Hastings! You should establish a harem!”

“It’s all very well to rag me. Mademoiselle Daubreuil is a very beautiful girl, and I do admire her immensely—I don’t mind admitting it. The other’s nothing—don’t suppose I shall ever see her again. She was quite amusing to talk to just for a railway journey, but she’s not the kind of girl I should ever get keen on.”

“Why?”

“Well—it sounds snobbish perhaps—but she’s not a lady, not in any sense of the word.”

Poirot nodded thoughtfully. There was less raillery in his voice as he asked:

“You believe, then, in birth and breeding?”

“I may be old-fashioned, but I certainly don’t believe in marrying out of one’s class. It never answers.”

“I agree with you, mon ami. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, it is as you say. But there is always the hundredth time! Still, that does not arise, as you do not propose to see the lady again.”

His last words were almost a question, and I was aware of the sharpness with which he darted a glance at me. And before my eyes, writ large in letters of fire, I saw the words “Hôtel du Phare,” and I heard again her voice saying “Come and look me up” and my own answering with empressement: “I will.”

Well, what of it? I had meant to go at the time. But since then, I had had time to reflect. I did not like the girl. Thinking it over in cold blood, I came definitely to the conclusion that I disliked her intensely. I had got hauled over the coals for foolishly gratifying her morbid curiosity, and I had not the least wish to see her again.

I answered Poirot lightly enough.

“She asked me to look her up, but of course I shan’t.”

“Why ‘of course’?”

“Well—I don’t want to.”

“I see.” He studied me attentively for some minutes. “Yes. I see very well. And you are wise. Stick to what you have said.”

“That seems to be your invariable advice,” I remarked, rather piqued.

“Ah, my friend, have faith in Papa Poirot. Some day, if you permit, I will arrange you a marriage of great suitability.”

“Thank you,” I said laughing, “but the prospect leaves me cold.”

Poirot sighed and shook his head.

“Les Anglais!” he murmured. “No method—absolutely none whatever. They leave all to chance!” He frowned, and altered the position of the salt cellar.

“Mademoiselle Cinderella is staying at the Hôtel d’Angleterre you told me, did you not?”

“No. Hôtel du Phare.”

“True, I forgot.”

A moment’s misgiving shot across my mind. Surely I had never mentioned any hotel to Poirot. I looked across at him, and felt reassured. He was cutting his bread into neat little squares, completely absorbed in his task. He must have fancied I had told him where the girl was staying.

We had coffee outside facing the sea. Poirot smoked one of his tiny cigarettes, and then drew his watch from his pocket.

“The train to Paris leaves at 2:25,” he observed. “I should be starting.”

“Paris?” I cried.

“That is what I said, mon ami.”

“You are going to Paris? But why?”

He replied very seriously.

“To look for the murderer of M. Renauld.”

“You think he is in Paris?”

“I am quite certain that he is not. Nevertheless, it is there that I must look for him. You do not understand, but I will explain it all to you in good time. Believe me, this journey to Paris is necessary. I shall not be away long. In all probability I shall return tomorrow. I do not propose that you should accompany me. Remain here and keep an eye on Giraud. Also cultivate the

Comments (0)