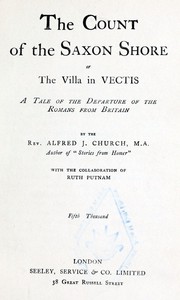

The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (fantasy books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Church and Putnam

Book online «The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (fantasy books to read TXT) 📗». Author Church and Putnam

It would be needless to describe the rest of the villa. It was like the houses of its kind, houses which the Romans erected wherever they went in as close an imitation as they could make of what they were accustomed to at home.

The garden, however, must not be wholly passed over. Spacious and handsome as it was, it in part presented a stiff and unnatural appearance, looking, in fact, somewhat theatrical, as contrasted with the pastoral sunniness of the landscape. A Roman gardener had been brought from Rome—one skilled in all the arts of his craft. It was he who had terraced the slope with so much regularity, had planted stiff box hedges—and, above all, it was his taste which led him to cut and train box and laburnum shrubs into fantastic imitations of other forms. The poor trees were forced to abandon their own natural shapes, and to pose as vases, geometrical figures, and animals of various kinds. There was even a ship of box surrounded by a broad channel of water, so that the spectator, making large demands on his imagination, might imagine that the little mock vessel was moored on a still sheet of water. Among the box trees were stone fountains badly copied from classic models. But these had not remained in their bare crudity. The loving British ivy had crept close around them, and added a grace which the sculptor had failed to give. The Roman gardener would have liked to banish [pg 44]this intruder, or to at least train it into the positions prescribed by horticultural rules, but he had been bidden to let it run at its own sweet will; and so it had, and had flourished, well nursed by the soft and humid atmosphere.

Scattered at regular intervals through the green were flower-beds stocked with plants, which were either native to the island, or had been brought hither with great care from the capital. There were roses in several varieties, strange-shaped orchids, which had been found growing wild at lower levels of the island, and adopted into this civilized garden to ornament it with their unique beauty. Gay geraniums and other flowers made throughout the summer bright patches of colour in striking contrast to the dark green.

These beds were enclosed by borders. Between these enclosures were curiously-cut letters of growing box, which perpetuated—at least for the life-time of the shrub—the gardener’s own name or that of his master, or classic titles, to serve as designations for certain portions of the place. In the midst of the garden several luxuriant oaks and graceful elms had been allowed to retain in their native freedom the shapes into which they had been growing for so many years. They cast wide shadows, and gave a softened aspect to the unnatural shapes of the trained growths.

[pg 45]Beyond the floral division of the garden was another enclosure for pear and apple trees. They stood on a green sward, soft as velvet, and of a deeper hue than Italian suns permit to the grass on which they smile. Here, too, were foreign embellishments. The monotony of the uniform rows of fruit trees was varied by pyramids of box, and the whole orchard was surrounded by a belt of plane trees.

A circle of oaks had been left at the summit of one of the terraces. Thick hedges were planted between the trees, making a dense wall, in which openings were cut for the view, so that the vista was visible, like a picture set in a dark frame. This green room, roofed by the sky, was paved with a mosaic of the bright coloured chalk from the cliffs at the western end of the island, and contained an oblong basin of water shaped like a table. The water flowed through so gently that the surface always seemed at rest, and yet never grew warm. Couches were placed at this fountain table, and from time to time repasts were served here, certain viands being placed in dishes shaped like swans or boats, which floated gracefully on the watery surface. The more solid meats were placed on the broad marble edges of the basin.

This sylvan retreat seemed made for a meeting of naiads and nereids. In short, the spot was so [pg 46]sheltered, the outlook over sea and land both near and across the strait so fair, that one could well believe even Pliny’s famed Tuscan garden, which may have suggested some features of this British one, was not more happily placed.

CARNA.

When Ælius had come, some eighteen years before the beginning of our story, to take up his command on the coast of Britain, he had brought with him his young wife. This lady, always delicate in health, had not long survived her transplantation to a northern climate. Six months after her arrival in Britain she had died in giving birth to a daughter. The child was entrusted to the care of a British woman, wife of the sailing master of one of the Roman ships, who had reared her together with her own daughter. When little Ælia was but a few weeks old her foster-mother had become a widow, her husband having met with his death in a desperate encounter with one of the Saxon cruisers. This misfortune had been followed by another, the loss of her two elder children, who had been carried off by a malarious fever. The widow, thus doubly bereaved, had thankfully accepted the Count’s offer that she [pg 48]should take the post of mother of the maids in his household. Her foster-daughter, a feeble little thing, whom she had the greatest difficulty in rearing, was as dear to her as was her own child, and the new arrangement ensured that she should not be separated from her. For ten years she was as happy as a woman who had lost so much could hope to be. She had the pleasure of seeing her delicate nursling pass safely through childhood, and grow into a handsome, vigorous girl. Then her own call came; and feeling that her earthly work was done, she had been glad to meet it. The Count, who was a frequent visitor to her deathbed, had no difficulty in promising her that the two children should never be separated. Indeed he could not have

Comments (0)