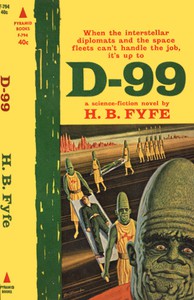

D-99: a science-fiction novel by H. B. Fyfe (cool books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: H. B. Fyfe

Book online «D-99: a science-fiction novel by H. B. Fyfe (cool books to read TXT) 📗». Author H. B. Fyfe

Johnson, a moment later, grimaced. His expression became apologetic.

"Don't say things like that!" he told Smith, turning again to the screen. "It slipped through my mind as I heard you, and he didn't like it!"

"Who? Harris?"

"No, the fish at his end. I apologized for you."

There was a general restless shifting of feet in the Terran office. Smith seemed, in the dim lighting of the communications room, to flush a deeper shade.

"And what does Harris say?"

Johnson inquired. Harris requested that they get him out.

"Goddammit!" muttered Smith. "He must be punchy!"

"It happens," Lydman reminded him softly.

"Yes," said Smith, after a startled look around, "but some were like that to begin with, and his record suggests it all the way."

He asked Johnson to get a description of the place where Harris found himself. The answer was, in a fashion, conclusive.

"Like any other part of the sea bottom," reported Johnson. "And, furthermore, he's tired of thinking and wants to rest."

"Who does?" demanded Smith.

"They won't tell me," said Johnson, sadly.

Smith choked off a curse, noticing Simonetta standing there. He combed his hair furiously with both hands. No one suggested any other questions, so he thanked Johnson and told Joe to break off.

"At least, we know it's all real," he sighed. "He was actually taken, and he's still alive."

"You put a lot of faith in a couple of fish," said Lydman.

Smith hesitated.

"Well ... now ... they aren't really fish," he said. "Let's not build up a mental misconception, just because we've been kidding about 'swishy the thinking fishy.' Actually, they probably wouldn't even suggest fish to an ichthyologist, and they may be a pretty high form of life."

"They may be as high as this Harris," commented Parrish, and earned a cold stare from Lydman.

"I think I'll look around the lab," said the latter, as the others made motions toward breaking up the gathering.

Westervelt promptly headed for the door. He saw that Lydman was walking around the corner of the wire mesh partition that enclosed the special apparatus of the communications room, doubtless bent upon taking a short-cut into the lab.

I want to go sit down a while before they pin me on him again, thought the youth. I need fifteen minutes, then I'll relieve whoever has him, if Smitty wants me to.

TWELVEThe light, impotent after penetrating fifty fathoms of Tridentian sea, was murky and green-tinted; but Tom Harris had become more or less used to that. It rankled, nevertheless, that the sea-people continued to ignore his demands for a lamp.

He knew that they used such devices. Through the clear walls of his tank, he had seen night parties swimming out to hunt small varieties of fish. The water craft they piloted on longer trips and up to the surface were also equipped with lights powered by some sort of battery. It infuriated Harris to be forced arbitrarily to exist isolated in the dimness of the ocean bottom day or the complete blackness of night.

He rose from the spot where he had been squatting on his heels. So smooth was the glassy footing that he slipped and almost fell headlong. He regained his balance and looked about.

The tank was about ten by ten feet and twice as long, with metal angles which he assumed to be aluminum securing all edges. These formed the outer corners, so that he could see the gaskets inside them that made the tank water-tight. The sea-people, he had to admit, were quite capable of coping with their environment and understanding his.

The end of the tank distant from Harris was opaque. He thought that there were connections to a towing vehicle as well as to the plant that pumped air for him. The big fish had not made that quite clear to him. All other sides of the tank were quite clear. Whenever he walked about, he could look through the floor and find groups of shells and other remnants of deceased marine life in the white sand. Occasionally, he considered the pressure that would implode upon him should anything happen to rupture the walls, but he had become habitually successful in forcing that idea to the back of his mind.

Along each of the side walls were four little airlocks. The use of these was at the moment being demonstrated by one of the sea-people to what Harris was beginning to think of as a child.

The parent was slightly smaller than Harris, who stood five-feet-five and weighed a hundred and thirty pounds Terran. It also had four limbs, but that was about the last point they had in common. The Tridentian's limbs all joined his armored body near the head. Two of them ended in powerful pincers; the others forked into several delicate tentacles. The body was somewhat flexible despite the weight of rugged shell segments, and tapered to a spread tail upon which the crustacean balanced himself easily.

Harris felt at a distinct disadvantage in the vision department: each of the Tridentians had four eyes protruding from his chitinous head. The adult had grown one pair of eye-stalks to a length of nearly a foot. The second pair, like both of the youngster's, extended only a few inches.

The Terran could not be sure whether the undersea currency consisted of metal or shell, but the Tridentian deposited some sort of coin in a slot machine outside one of the little airlocks. It caused a grinding noise. Directly afterward, a small lump of compressed fish, boned, was ejected from an opening on the inside.

"Goddam' blue lobsters!" swore Harris. "Think they're doing me a favor!"

He let them wait a good five minutes before he decided that the prudent course was to accept the offering. Sneering, he walked over and picked up the food. There was usually little else provided. On days he had been too angry or too disgusted to accept the favors of sightseers, his keepers assumed that he was not hungry.

In the beginning, he had also had a most difficult time getting through to them his need for fresh water. That was when he had come to believe in the large, fish-like swimmer who had transmitted his thoughts to the sea-people. The fact that the latter could and did produce fresh water for him aroused his grudging respect, even though the taste was nothing to take lightly.

He juggled the lump of fish in one hand, causing the little Tridentian to twirl his eye-stalks in glee and swim up off the ocean bottom to look down through the top of the tank. The parent also wiggled his eye-stalks, more sedately. Harris suspected them of laughing, and turned his back.

Looking through the other side of his tank, he could see—to such distance as the murky light permitted—the parked vehicles of the Tridentians. Like a collection of small boats, they were of sundry sizes and shapes, depending perhaps upon each owner's fancy, perhaps on his skill. Harris did not know whether the Tridentians' craftsmanship extended to the level of having professional builders. At any rate, they were spread out like a small city. Among them were tent-like arrangements of nets to keep out swimming vermin. Other than that, the sea-people used no shelters.

They were smart enough to build a cage for me! he thought bitterly. What the hell is the matter with the Terran government, anyway? That Department of Interstellar Relations, or whatever they call it. Why can't they get me out of here? And where did Big Fish go now?

He saw several of the crustacean people approaching from the camping area. Shortly, no doubt, he would again be a center of mass attention, with cubes of compressed and stinking fish shooting at him from all the little airlocks. He snarled wordlessly.

The groups seemed to come at certain periods which he had been unable to define. He could only guess that they had choice times for hunting besides other work that had to be done to maintain the campsite and their jet-propelled craft.

I'd like to get one of them in here and boil him! thought Harris. Big Fish claims they don't taste good. I wonder. Anyway, it would shake them up!

He had long since given up thinking about what the sea-people could do to him if they chose. Their flushing the tank eighteen inches deep with sea water twice a day had soon given him an idea, especially as he had nowhere to go during the process. He no longer permitted himself to fall asleep anywhere near the inlet pipe.

He noticed that the dozen or so sightseers were edging around the end of the tank to join the first individual and his offspring. Looking up, Harris saw the reason. A long, dark shadow was curving down in an insolently deliberate dive. It was streamlined as a Terran shark and as long as the tank in which Harris lived. The flat line of its leading edge split into something very like a yawn, displaying astonishing upper and lower carpets of conical teeth. This was possible because the eyes, about eight Harris thought, were spaced in a ring about the head end of the long body.

They know I don't like to eat them, but I like to scare them a little. Big Fish thought to Harris. Look at them trying to smile at me!

Harris watched the Tridentians wiggling and waving their eye-stalks as the monster passed lazily over them and turned to come slowly back.

"I'd like to scare them a lot," said Harris, who had learned some time ago that he got through better just by forgetting telepathy and verbalizing. "Is the D.I.R. man still there?"

Which ... what you thought? inquired Big Fish.

"The other Terran, the one on the island."

The other air-breathing one is gone, the other Big Fish is feeding, as I have done just now, and it is not clear about the far Terran who lacks a Big Fish.

"All the bastards on both worlds are out to lunch," growled Harris, "and here I sit!"

You are in to lunch, agreed the monster.

The three eyes that bore upon the imprisoned man as the thinker swept past the tank had an intelligent alertness. Harris had come to imagine that he could detect expressions on Big Fish's limited features.

"You're the only friend I've got!" he exclaimed, slipping suddenly into self-pity. "I wish I could go with you."

Once you could, when you had your own tank.

"It was what we call a submarine," said Harris. "I was looking to see what was on the ocean floor. Tell me, is it all like this?"

Is it all like what? With blue lobsters?

Harris still retained enough sanity to realize that the Tridentians did not suggest Terran lobsters to this being who probably could not even imagine them. That was an automatic translation of thought furnished out of his own memory and name-calling.

"No," he said. "I mean is it all sand and mud with a few chasms here and there? Where do these crabs get their metals?"

There are different kinds of holes and hills. It is all mostly the same. You cannot swim in it anywhere, although there are little things that dig under the soft sand. Some of them are good to eat but you have to spit out a lot of sand. The crabs dig with machines sometimes, in big holes, but what they catch I do not know.

"Isn't there anything that catches them?" asked Harris bitterly.

No. They are big enough to catch other things, except a few. Things that are bigger than I am are not smart.

The monster made a pass along the ocean bed near the Tridentians, stirring up a cloud of sand and causing Harris's captor to shrink against the side of his tank. The Terran laughed heartily. He clapped the backs of his fists against his forehead above the eyes and wiggled his forefingers at the Tridentians on the other side of the clear barrier.

Even after the sand had settled, he ran back and forth along the side of his tank, making sure that every sightseer had opportunity to note his gesture. He had an idea that they did not like it much.

They do not like it at all, thought Big Fish. Some of them are asking for the man who lets the sea into your tank.

"Don't call it a man!" objected Harris, giving up his posturing. "I am a man."

What else can I call these men except men? asked the other. I do not understand why you want to be called a man. You are different.

"Forget it," said Harris. "It was just a figure of thought."

He felt like sitting down again, but decided against it in case the onlookers should succeed in obtaining the services of the tank attendant. He walked to the end of the tank, where he could stare into the greenish distance without looking at the Tridentian camp.

"I wish

Comments (0)