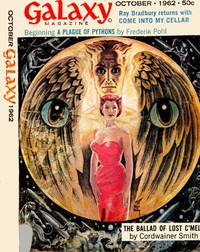

Plague of Pythons by Frederik Pohl (websites to read books for free .txt) 📗

- Author: Frederik Pohl

Book online «Plague of Pythons by Frederik Pohl (websites to read books for free .txt) 📗». Author Frederik Pohl

And he was free again, but there was a sudden burst of screams from outside.

Bewildered, Chandler stood for a moment, as little able to move as though the girl still had him under control. Then he leaped through a classroom to a window, staring. Outside in the playground there was wild confusion. Half the spectators were on the ground, trying to rise. As he watched, a teen-age boy hurled himself at an elderly lady, the two of them falling. Another man flung himself to the ground. A woman swung her pocketbook into the face of the man next to her. One of the fallen ones rose, only to trip himself again. It was a mad spectacle, but Chandler understood it: What he was watching was a single member of the exec trying to keep a group of twenty ordinary, unarmed human beings in line. The exec was leaping from mind to mind; even so, the crowd was beginning to scatter.

Without thought Chandler started to leap out to help them; but the possessor had anticipated that. He was caught at the door. He whirled and ran toward the woman with the mop; as he was released, the woman flung herself upon him, knocking him down.

By the time he was able to get up again it was far too late to help ... if there ever had been a time when he could have been of any real help.

He heard shots. Two policeman had come running into the playground, with guns drawn.

The exec who had looked at him out of the boy's eyes, who had penetrated this nest of enemies and extricated Chandler from it, had taken first things first. Help had been summoned. Quick as the coronets worked, it was no time at all until the nearest persons with weapons were located, commandeered and in action.

Two minutes later there no longer was resistance.

Obviously more execs had come to help, attracted by the commotion perhaps, or summoned at some stolen moment after the meeting had first been invaded. There were only five survivors on the field. Each was clearly controlled. They rose and stood patiently while the two police shot them, shot them, paused to reload and shot again. The last to die was the bearded man, Linton, and as he fell his eyes brushed Chandler's.

Chandler leaned against a wall.

It had been a terrible sight. The nearness of his own death had been almost the least of it.

He had no doubt of the identity of the exec who had saved him and destroyed the others. Though he had heard the voice only as it came from his own mouth, he could not miss it. It was Rosalie Pan.

He looked out at the red-headed man, sprawled across the foul line behind third base, and remembered what he had said. There weren't any good execs or bad execs. There were only execs.

XI

Whatever Chandler's life might be worth, he knew he had given it away and the girl had given it back to him.

He did not see her for several days, but the morning after the massacre he woke to find a note beside his bed table. No one had been in the room. It was his own sleeping hand that had written it, though the girl's mind had moved his fingers:

If you get mixed up in anything like that again I won't be able to help you. So don't! Those people are just using you, you know. Don't throw away your chances. Do you like surfboarding?

Rosie

But by then there was no time for surfboarding, or for anything else but work. The construction job on Hilo had begun, and it was a nightmare. He was flown to the island with the last load of parts. No execs were present in the flesh, but in the first day Chandler lost count of how many different minds possessed his own. He began to be able to recognize them by a limp as he walked, by tags of German as he spoke, by a stutter, a distinctive gesture of annoyance, an expletive. As he was a trained engineer he was left to labor by himself for hours on end. It was worse for the others. There seemed to be a dozen execs hovering invisible around all the time; no sooner was a worker released by one than he was seized by another. The work progressed rapidly, but at the cost of utter exhaustion. By the end of the fourth day Chandler had eaten only two meals and could not remember when he had slept last. He found himself staggering when free, and furious with the fatigue-clumsiness of his own body when possessed. At sundown on the fourth day he found himself free for a moment and, incredibly, without work of his own to do just then, until someone else completed a job of patchwiring. He stumbled out into the open air and had time only to gaze around for a moment before his eyes began to close. This must once have been a lovely island. Even unkempt as it was, the trees were tall and beautiful. Beyond them a wisp of smoke was pale against the dark-blue evening sky; the breeze was scented.... He woke and found he was already back in the building, reaching for his soldering gun.

There came a point at which even the will of the execs was unable to drive the flogged bodies farther, and then they were permitted to sleep for a few hours. At daybreak they were awake again. The sleep was not enough. The bodies were slow and inaccurate. Two of the Hawaiians, straining a hundred-pound component into place, staggered, slipped—and dropped it.

Appalled, Chandler waited for them to kill themselves.

But it seemed that the execs were tiring too. One of the Hawaiians said irritably, with an accent Chandler did not recognize: "That's pau. All right, you morons, you've won yourselves a vacation; we'll have to fly you in replacements. Take the day off." And incredibly all eleven of the haggard wrecks stumbling around the building were free at once.

The first thought of every man was to eat, to relieve himself, to remove a shoe and ease a blistered foot—to do any of the things they had not been permitted to do. The second thought was sleep.

Chandler dropped off at once, but he was overtired; he slept fitfully, and after an hour or two of turning on the hard ground sat up, blinking red-eyed around. He had been slow. The cushioned seats in the aircraft and cars were already taken. He stood up, stretched, scratched himself and wondered what to do next, and he remembered the thread of smoke he had seen—when? three nights ago?—against the evening sky.

In all those hours he had not had time to think one obvious thought: There should have been no smoke there! The island was supposed to be deserted.

He stood up, looked around to get his bearings, and started off in the direction he remembered.

It was good to own his body again, in poor condition as it was. It was delicious to be allowed to think consecutive thoughts.

The chemistry of the human animal is such that it heals whatever thrusts it may receive from the outside world. Short of death, its only incapacitating wound comes from itself; from the outside it can survive astonishing blows, rise again and flourish. Chandler was not flourishing, but he had begun to rise.

Time had been so compressed and blurred in the days since the slaughter at the Punahou School that he had not had time to grieve over the deaths of his briefly-met friends, or even to think of their quixotic plans against the execs. Now he began to wonder.

He understood with what thrill of hope he had been received—a man like themselves, not an exec, whose touch was at the very center of the exec power. But how firm was that touch? Was there really anything he could do?

It seemed not. He barely understood the mechanics of what he was doing, far less the theory behind it. Conceivably knowing where this installation was he could somehow get back to it when it was completed. In theory it might be that there was a way to dispense with the headsets and exert power from the big board itself.

A Cro-Magnard at the controls of a nuclear-laden jet bomber could destroy a city. Nothing stopped him. Nothing but his own invincible ignorance. Chandler was that Cro-Magnard; certainly power was here to grasp, but he had no way of knowing how to pick it up.

Still—where there was life there was hope. He decided he was wasting time that would not come again. He had been wandering along a road that led into a small town, quite deserted, but this was no time for wandering. His place was back at the installation, studying, scheming, trying to understand all he could. He began to turn, and stopped.

"Great God," he said softly, looking at what he had just seen. The town was deserted of life, but not of death.

There were bodies everywhere.

They were long dead, perhaps years. They seemed natural and right as they lay there. It was not surprising they had escaped his notice at first. Little was left but bones and an occasional desiccated leathery rag that might have been a face. The clothing was faded and rotted away; but enough was left of the bodies and the clothes to make it clear that none of these people had died natural deaths. A rusted blade in a chest cage showed where a knife had pierced a heart; a small skull near his feet (with a scrap of faded blue rompers near it) was shattered. On a flagstone terrace a family group of bones lay radiating outward, like a rosette. Something had exploded there and caught them all as they turned to flee. There was a woman's face, grained like oak and eyeless, visible between the fender of a truck and a crushed-in wall.

Like exhumed Pompeii, the tragedy was so ancient that it aroused only wonder. The whole town had been blotted out.

The execs did not take chances; apparently they had sterilized the whole island—probably had sterilized all of them except Oahu itself, to make certain that their isolation was complete, except for the captive stock allowed to breed and serve them in and around Honolulu.

Chandler prowled the town for a quarter of an hour, but one street was like another. The bodies did not seem to have been disturbed even by animals, but perhaps there were none big enough to show traces of such work.

Something moved in a doorway.

Chandler thought at once of the smoke he had seen, but no one answered his call and, though he searched, he could neither see nor hear anything alive.

The search was a waste of time. It also wasted his best chance to study the thing he was building. As he returned to the cinder-block structure at the end of the airstrip he heard motors and looked up to see a plane circling in for a landing.

He knew that he had only a few minutes. He spent those minutes as thriftily as he could, but long before he could even grasp the circuitry of the parts he had not himself worked on he felt a touch at his mind. The plane was rolling to a stop. He and all of them hurried over to begin unloading it.

The plane was stopped with one wingtip almost touching the building, heading directly into it—convenient for unloading, but a foolish nuisance when it came time to turn it and take off again, Chandler's mind thought while his body lugged cartons out of the plane.

But he knew the answer to that. Takeoff would be no problem, any more than it would for the other small transports at the far end of the strip.

These planes were not going to return, ever.

The work went on, and then it was done, or all but, and Chandler knew no more about it than when it was begun. The last little bit was a careful check of line voltages and a balancing of biases. Chandler could help only up to a point, and then two execs, working through the bodies of one of the Hawaiians

Comments (0)