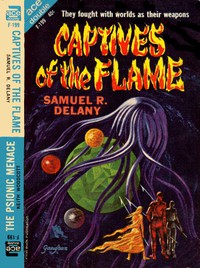

Captives of the Flame by Samuel R. Delany (good books for high schoolers .TXT) 📗

- Author: Samuel R. Delany

Book online «Captives of the Flame by Samuel R. Delany (good books for high schoolers .TXT) 📗». Author Samuel R. Delany

Then the boy saw Tloto on the other side of the clearing, his nostrils quivering, his blind head turning back and forth. Somehow the slug-man must have maneuvered the animal into the trap. He wasn't sure how, but that must have been what had happened.

The urge that welled in him now came too fast to be stopped. It had too much to do with the recognition of luck, and the general impossibility of the whole situation. The boy laughed.

He startled himself with the sound, and after a few seconds stopped. Then he turned. Quorl stood behind him.

(Squeeeee ... Squeeee ... raaaaaaa! Then a gurgle, then nothing.)

Quorl was smiling too, a puzzled smile.

"Why did you—?" (The last word was new. He thought it meant laugh, but he said nothing.)

The boy turned back now. Tloto and the pig were gone.

Quorl walked the boy back to their camp. As they were nearing the stream Quorl saw the boy's footprints in the soft earth and frowned. "To leave your footprints in wet earth is dangerous. The vicious animals come to drink and they will smell you, and they will follow you, to eat. Suppose that pig had smelled them and been chasing you, instead of running into the pool? What then? If you must leave your footprints, leave them in dry dust. Better not to leave them at all."

The boy listened, and remembered. But that night, he saved a large piece of meat from his food. When Tloto came into the circle of firelight, he gave it to him.

Quorl gave a shrug of disgust and flung a pebble at the retreating shadow. "He is useless," Quorl said. "Why do you waste good food on him? To throw away good food is a—." (Unintelligible word.) "You do not understand—." (Another unintelligible word.)

The boy felt something start up inside him again. But he would not let it move his tongue; so he laughed. Quorl looked puzzled. The boy laughed again. Then Quorl laughed too. "You will learn. You will learn at last." Then the giant became serious. "You know, that is the first—sound I have heard you make since coming here."

The boy frowned, and the giant repeated the sentence. The boy's face showed which word baffled him.

The giant thought a minute, and then said, "You, me, even Tloto, are malika." That was the word. Now Quorl looked around him. "The trees, the rocks, the animals, they are not malika. But the laughing sound, that was a malika sound."

The boy thought about it until perhaps he understood. Then he slept.

He laughed a lot during the days now. Survival had come as close to routine as it could here in the jungle, and he could turn his attention to more malika concerns. He watched Quorl when they came on other forest people. With single men and women there was usually only an exchange of ten or twelve friendly words. If it were a couple, especially with children, he would give them food. But if they passed anyone with scars, Quorl would freeze until the person was by.

Once the boy wandered to the temple on the arena of rock. There were carvings on much of the stone. The sun was high. The carvings represented creatures somewhere between fish and human. When he looked up from the rock, he saw that the priest had come from the temple and was staring at him. The priest stared until he went away.

Now the boy tried to climb the mountain. That was hard because the footing was slippery and the rocks kept giving. At last he stopped on a jutting rock that looked down the side of the mountain. He was far from any place he knew. He was very high. He stood with hand against the leaning trunk of a near rotten tree, breathing deep and squinting at the sky. (Three or four times Quorl and he had taken long hunting trips: one had taken them to the edge of a deserted meadow across which was a crazily sagging farmhouse. There were no people there. Another had taken them to the edge of the jungle, beyond which the ground was gray and broken, and row after row of unsteady shacks sat among clumps of slithering ferns. Many of the forest people living there had scars and spent more time in larger groups.) The boy wondered if he could see to the deserted meadow from here, or to the deadly rows of prison shacks. A river, a snake of light, coiled through the valley toward the sea. The sky was very blue.

He heard it first, and then he felt it start. He scrambled back toward firmer ground but didn't scramble fast enough. The rock tilted, tore loose, and he was falling. (It pierced through his memory like a white fire-blade hidden under canvas: "... knees up, chin down, and roll quick," the girl had said a long time ago.) It was perhaps twenty feet to the next level. Tree branches broke his fall and he hit the ground spinning, and rolled away. Something else, the rock or a rotten log, bit the ground a moment later where he had been. He uncurled too soon, reaching out to catch hold of the mountain as it tore by him. Then he hit something hard; then something hit him back, and he sailed off into darkness in a web of pain.

Much later he shook his head, opened his eyes, then chomped his jaws on the pain. But the pain was in his leg, so chomping didn't help. He moved his face across crumbling dirt. The whole left side of his body ached, the type of ache that comes when the muscles are tensed to exhaustion but will not relax.

He tried to crawl forward, and went flat down onto the earth, biting up a mouthful of dirt. He nearly tore his leg off.

He had to be still, calm, find out exactly what was wrong. He couldn't tear himself to pieces like the wildcat who had gotten caught in the sprung trap and who had bled to death after gnawing off both hind legs. He was too malika.

But each movement he made, each thought he had, happened in the blurring green haze of pain. He raised himself up and looked back. Then he lay down again and closed his eyes. A log the thickness of his body lay across his left leg. Once he tried to push it away but only bruised his palm against the bark, and at last went unconscious with the effort.

When he woke up, the pain was very far away. The air was darkening. No, he wasn't quite awake. He was dreaming about something, something soft, a little garden, with shadows blowing in at the edge of his vision swift and cool, a little garden behind the—

Suddenly, very suddenly, it struck him what was happening, the slowing down of thoughts, his breathing, maybe even his heart. Then he was struggling again, struggling hard enough that had he still the strength, he would have torn himself in half, knowing while he struggled that perhaps the wildcat had been malika after all, or not caring if he were less, only fighting to pull himself away from the pain, realizing that blood had begun to seep from beneath the log again, just a tiny trickle.

Then the shadows overtook him, the dreams, the wisps of forgetfulness gauzing his eyes.

Tloto nearly had to drag Quorl halfway up the mountain before the giant got the idea. When he did, he began to run. Quorl found the boy; just before sunset. He was breathing in short gasps, his fists clenched, his eyes closed. The blood on the dirt had dried black.

The great brown hands went around the log, locked, and started to shift it; the boy let out a high sound from between his teeth.

The hands, roped with vein and ridged with ligament, strained the log upward; the sound became a howl.

The giant's feet braced against the dirt, slid into the dirt, and the hands that had snapped tiny necks and bound sticks together with gut string, pulled; the howl turned into a scream. He screamed again. Then again.

The log coming loose tore away nearly a square foot of flesh from the boy's leg. Then, Quorl went over and picked him up.

This is the best dream, the boy thought, from that dark place he had retreated to behind the pain, because Quorl is here. The hands were lifting him now, he was held close, warm, somehow safe. His cheek was against the hard shoulder muscle, and he could smell Quorl too. So he stopped screaming and turned his head a little to make the pain go away. But it wouldn't go. It wouldn't. Then the boy cried.

The first tears through all that pain came salty in his eyes, and he cried until he went to sleep.

Quorl had medicine for him the next day ("From the priest," he said.) which helped the pain and made the healing start. Quorl also had made the boy a pair of wooden crutches that morning. Although muscle and ligament had been bruised and crushed and the skin torn away, no bone had broken.

That evening there was a drizzle and they ate under the canopy. Tloto did not come, and this time it was Quorl who saved the extra meat and kept looking off into the wet gray trees. Quorl had told the boy how Tloto had led him to him; when they finished eating, Quorl took the meat and ducked into the drizzle.

The boy lay down to sleep. He thought the meat was a reward for Tloto. Only Quorl had seemed that night full of more than usual gravity. The last thing he wondered before sleep flooded his eyes and ears was how blind, deaf Tloto had known where he was anyway.

When he woke it had stopped raining. The air was damp and chill. Quorl had not come back.

The sound of the blown shell came again. The boy sat up and flinched at the twinge in his leg. To his left the moon was flickering through the trees. The sound came a third time, distant, sharp, yet clear and marine. The boy reached for his crutches and hoisted himself to his feet. He waited till the count of ten, hoping that Quorl might suddenly return to go with him.

A last he took a deep breath and started haltingly forward. The faint moonlight made the last hundred yards easy going. Finally he reached a vantage where he could look down through the wet leaves onto the arena of stone.

The sky was sheeted with mist and the moon was an indistinct pearl in the haze. The sea was misty. People were already gathered at the edge. The boy looked at the priest and then ran his eye around the circle of people. One of them was Quorl!

He leaned forward as far as he could. The priest sounded the shell again and the prisoners came out of the temple: first three boys, then an older girl, then a man. The next one ... Tloto! It was marble-white under the blurred moon. Its clubbed feet shuffled on the rock. Its blind head ducked right and left with bewilderment.

As the priest raised the long three-pronged knife, the boy's hands went tight around the crutches. He passed from one prisoner to the next. Tloto cringed, and the boy sucked in a breath as the knife went down, feeling his own flesh part under the blades. Then the murmur died, the prisoners were unbound, and the people filed from the rock back into the forest.

The boy waited to see which way Quorl headed before he started through moon-dusted bushes as fast as his crutches would let him. There were many people on the webbing of paths that came from the temple rock. There was Quorl!

When he caught up, Quorl saw him and slowed down. Quorl didn't look at him, though. Finally the giant said, "You don't understand. I had to catch him. I had to give him to the old one to be marked. But you don't understand." The boy hardly looked at all where they were going, but stared up at the giant.

"You don't understand," Quorl said again. Then he looked at the boy and was quiet for a minute. "No, you don't," he repeated. "Come." They turned off the main path now, going slower. "It's a ... custom. An important custom. Yes, I know it hurt him. I know he was afraid. But it had to be. Tloto is one of those who—." (The word was some inflection of the verb to know.) Quorl was silent for

Comments (0)