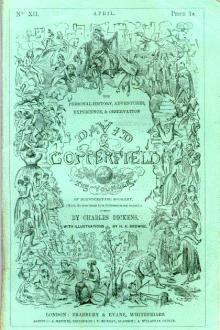

David Copperfield - Charles Dickens (great books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: 0679783415

Book online «David Copperfield - Charles Dickens (great books to read .TXT) 📗». Author Charles Dickens

The handsome lady - so like, oh so like! - regarded me with a fixed look, and put her hand to her forehead. I besought her to be calm, and prepare herself to bear what I had to tell; but I should rather have entreated her to weep, for she sat like a stone figure.

‘When I was last here,’ I faltered, ‘Miss Dartle told me he was sailing here and there. The night before last was a dreadful one at sea. If he were at sea that night, and near a dangerous coast, as it is said he was; and if the vessel that was seen should really be the ship which -‘

‘Rosa!’ said Mrs. Steerforth, ‘come to me!’

She came, but with no sympathy or gentleness. Her eyes gleamed like fire as she confronted his mother, and broke into a frightful laugh.

‘Now,’ she said, ‘is your pride appeased, you madwoman? Now has he made atonement to you - with his life! Do you hear? - His life!’

Mrs. Steerforth, fallen back stiffly in her chair, and making no sound but a moan, cast her eyes upon her with a wide stare.

‘Aye!’ cried Rosa, smiting herself passionately on the breast, ‘look at me! Moan, and groan, and look at me! Look here!’ striking the scar, ‘at your dead child’s handiwork!’

The moan the mother uttered, from time to time, went to My heart. Always the same. Always inarticulate and stifled. Always accompanied with an incapable motion of the head, but with no change of face. Always proceeding from a rigid mouth and closed teeth, as if the jaw were locked and the face frozen up in pain.

‘Do you remember when he did this?’ she proceeded. ‘Do you remember when, in his inheritance of your nature, and in your pampering of his pride and passion, he did this, and disfigured me for life? Look at me, marked until I die with his high displeasure; and moan and groan for what you made him!’

‘Miss Dartle,’ I entreated her. ‘For Heaven’s sake -‘

‘I WILL speak!’ she said, turning on me with her lightning eyes. ‘Be silent, you! Look at me, I say, proud mother of a proud, false son! Moan for your nurture of him, moan for your corruption of him, moan for your loss of him, moan for mine!’

She clenched her hand, and trembled through her spare, worn figure, as if her passion were killing her by inches.

‘You, resent his self-will!’ she exclaimed. ‘You, injured by his haughty temper! You, who opposed to both, when your hair was grey, the qualities which made both when you gave him birth! YOU, who from his cradle reared him to be what he was, and stunted what he should have been! Are you rewarded, now, for your years of trouble?’

‘Oh, Miss Dartle, shame! Oh cruel!’

‘I tell you,’ she returned, ‘I WILL speak to her. No power on earth should stop me, while I was standing here! Have I been silent all these years, and shall I not speak now? I loved him better than you ever loved him!’ turning on her fiercely. ‘I could have loved him, and asked no return. If I had been his wife, I could have been the slave of his caprices for a word of love a year. I should have been. Who knows it better than I? You were exacting, proud, punctilious, selfish. My love would have been devoted - would have trod your paltry whimpering under foot!’

With flashing eyes, she stamped upon the ground as if she actually did it.

‘Look here!’ she said, striking the scar again, with a relentless hand. ‘When he grew into the better understanding of what he had done, he saw it, and repented of it! I could sing to him, and talk to him, and show the ardour that I felt in all he did, and attain with labour to such knowledge as most interested him; and I attracted him. When he was freshest and truest, he loved me. Yes, he did! Many a time, when you were put off with a slight word, he has taken Me to his heart!’

She said it with a taunting pride in the midst of her frenzy - for it was little less - yet with an eager remembrance of it, in which the smouldering embers of a gentler feeling kindled for the moment.

‘I descended - as I might have known I should, but that he fascinated me with his boyish courtship - into a doll, a trifle for the occupation of an idle hour, to be dropped, and taken up, and trifled with, as the inconstant humour took him. When he grew weary, I grew weary. As his fancy died out, I would no more have tried to strengthen any power I had, than I would have married him on his being forced to take me for his wife. We fell away from one another without a word. Perhaps you saw it, and were not sorry. Since then, I have been a mere disfigured piece of furniture between you both; having no eyes, no ears, no feelings, no remembrances. Moan? Moan for what you made him; not for your love. I tell you that the time was, when I loved him better than you ever did!’

She stood with her bright angry eyes confronting the wide stare, and the set face; and softened no more, when the moaning was repeated, than if the face had been a picture.

‘Miss Dartle,’ said I, ‘if you can be so obdurate as not to feel for this afflicted mother -‘

‘Who feels for me?’ she sharply retorted. ‘She has sown this. Let her moan for the harvest that she reaps today!’

‘And if his faults -‘ I began.

‘Faults!’ she cried, bursting into passionate tears. ‘Who dares malign him? He had a soul worth millions of the friends to whom he stooped!’

‘No one can have loved him better, no one can hold him in dearer remembrance than I,’ I replied. ‘I meant to say, if you have no compassion for his mother; or if his faults - you have been bitter on them -‘

‘It’s false,’ she cried, tearing her black hair; ‘I loved him!’

‘- if his faults cannot,’ I went on, ‘be banished from your remembrance, in such an hour; look at that figure, even as one you have never seen before, and render it some help!’

All this time, the figure was unchanged, and looked unchangeable. Motionless, rigid, staring; moaning in the same dumb way from time to time, with the same helpless motion of the head; but giving no other sign of life. Miss Dartle suddenly kneeled down before it, and began to loosen the dress.

‘A curse upon you!’ she said, looking round at me, with a mingled expression of rage and grief. ‘It was in an evil hour that you ever came here! A curse upon you! Go!’

After passing out of the room, I hurried back to ring the bell, the sooner to alarm the servants. She had then taken the impassive figure in her arms, and, still upon her knees, was weeping over it, kissing it, calling to it, rocking it to and fro upon her bosom like a child, and trying every tender means to rouse the dormant senses. No longer afraid of leaving her, I noiselessly turned back again; and alarmed the house as I went out.

Later in the day, I returned, and we laid him in his mother’s room. She was just the same, they told me; Miss Dartle never left her; doctors were in attendance, many things had been tried; but she lay like a statue, except for the low sound now and then.

I went through the dreary house, and darkened the windows. The windows of the chamber where he lay, I darkened last. I lifted up the leaden hand, and held it to my heart; and all the world seemed death and silence, broken only by his mother’s moaning.

One thing more, I had to do, before yielding myself to the shock of these emotions. It was, to conceal what had occurred, from those who were going away; and to dismiss them on their voyage in happy ignorance. In this, no time was to be lost.

I took Mr. Micawber aside that same night, and confided to him the task of standing between Mr. Peggotty and intelligence of the late catastrophe. He zealously undertook to do so, and to intercept any newspaper through which it might, without such precautions, reach him.

‘If it penetrates to him, sir,’ said Mr. Micawber, striking himself on the breast, ‘it shall first pass through this body!’

Mr. Micawber, I must observe, in his adaptation of himself to a new state of society, had acquired a bold buccaneering air, not absolutely lawless, but defensive and prompt. One might have supposed him a child of the wilderness, long accustomed to live out of the confines of civilization, and about to return to his native wilds.

He had provided himself, among other things, with a complete suit of oilskin, and a straw hat with a very low crown, pitched or caulked on the outside. In this rough clothing, with a common mariner’s telescope under his arm, and a shrewd trick of casting up his eye at the sky as looking out for dirty weather, he was far more nautical, after his manner, than Mr. Peggotty. His whole family, if I may so express it, were cleared for action. I found Mrs. Micawber in the closest and most uncompromising of bonnets, made fast under the chin; and in a shawl which tied her up (as I had been tied up, when my aunt first received me) like a bundle, and was secured behind at the waist, in a strong knot. Miss Micawber I found made snug for stormy weather, in the same manner; with nothing superfluous about her. Master Micawber was hardly visible in a Guernsey shirt, and the shaggiest suit of slops I ever saw; and the children were done up, like preserved meats, in impervious cases. Both Mr. Micawber and his eldest son wore their sleeves loosely turned back at the wrists, as being ready to lend a hand in any direction, and to ‘tumble up’, or sing out, ‘Yeo - Heave - Yeo!’ on the shortest notice.

Thus Traddles and I found them at nightfall, assembled on the wooden steps, at that time known as Hungerford Stairs, watching the departure of a boat with some of their property on board. I had told Traddles of the terrible event, and it had greatly shocked him; but there could be no doubt of the kindness of keeping it a secret, and he had come to help me in this last service. It was here that I took Mr. Micawber aside, and received his promise.

The Micawber family were lodged in a little, dirty, tumble-down public-house, which in those days was close to the stairs, and whose protruding wooden rooms overhung the river. The family, as emigrants, being objects of some interest in and about Hungerford, attracted so many beholders, that we were glad to take refuge in their room. It was one of the wooden chambers upstairs, with the tide flowing underneath. My aunt and Agnes were there, busily making some little extra comforts, in the way of dress, for the children. Peggotty was quietly assisting, with the old insensible work-box, yard-measure, and bit of wax-candle before her, that had now outlived so much.

It was not easy to answer her inquiries; still less to whisper Mr. Peggotty, when Mr. Micawber brought him in, that I had given the letter, and all was

Comments (0)