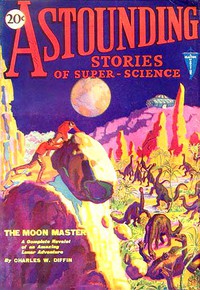

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 by Various (novels to improve english TXT) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 by Various (novels to improve english TXT) 📗». Author Various

"For scientific experiment!" she sobbed. "I'd rather die, John. I want an old-fashioned home, a Black Age family. I want to grow old with you and leave the earth to my children. Or else I want to die here now under the kind, white blanket the snow is already spreading over us." She drooped in his arms.

Clinging together, they stood in the howling wind, looking at each other hungrily, as though they would snatch from death this one last picture of the other.

[220] Northwood's freezing lips translated some of the futile words that crowded against them. "I love you because you are not perfect. I hate perfection!"

"Yes. Perfection is the only hopeless state, John. That is why Adam wanted to destroy, so that he might build again."

They were sitting in the snow now, for they were very tired. The storm began whistling louder, as though it were only a few feet above their heads.

"That sounds almost like the sun-ship," said Athalia drowsily.

"It's only the wind. Hold your face down so it won't strike your flesh so cruelly."

"I'm not suffering. I'm getting warm again." She smiled at him sleepily.

Little icicles began to form on their clothing, and the powdery snow frosted their uncovered hair.

Suddenly came a familiar voice: "Ach Gott!"

Dr. Mundson stood before them, covered with snow until he looked like a polar bear.

"Get up!" he shouted. "Quick! To the sun-ship!"

He seized Athalia and jerked her to her feet. She looked at him sleepily for a moment, and then threw herself at him and hugged him frantically.

"You're not dead?"

Taking each by the arm, he half dragged them to the sun-ship, which had landed only a few feet away. In a few minutes he had hot brandy for them.

While they sipped greedily, he talked, between working the sun-ship's controls.

"No, I wouldn't say it was a lucky moment that drew me to the sun-ship. When I saw Eve trying to charm John, I had what you American slangists call a hunch, which sent me to the sun-ship to get it off the ground so that Adam couldn't commandeer it. And what is a hunch but a mental penetration into the Fourth Dimension?" For a long moment, he brooded, absent-minded. "I was in the air when the black ray, which I suppose is Adam's deviltry, began to destroy everything it touched. From a safe elevation I saw it wreck all my work." A sudden spasm crossed his face. "I've flown over the entire valley. We're the only survivors—thank God!"

"And so at last you confess that it is not well to tamper with human life?" Northwood, warmed with hot brandy, was his old self again.

"Oh, I have not altogether wasted my efforts. I went to elaborate pains to bring together a perfect man and a perfect woman of what Adam called our Black Age." He smiled at them whimsically.

"And who can say to what extent you have thus furthered natural evolution?" Northwood slipped his arm around Athalia. "Our children might be more than geniuses, Doctor!"

Dr. Mundson nodded his huge, shaggy head gravely.

"The true instinct of a Creature of the Light," he declared.

Remember

ASTOUNDING STORIES

Appears on Newsstands

THE FIRST THURSDAY IN EACH MONTH

[221]

Into SpaceA loud hum filled the air, and suddenly the projectile rose, gaining speed rapidly.

Many of my readers will remember the mysterious radio messages which were heard by both amateur and professional short wave operators during the nights of the twenty-third and twenty-fourth of last September, and even more will remember the astounding discovery made by Professor Montescue of the Lick Observatory on the night of September twenty-fifth. At the time, some inspired writers tried to connect the two events, maintaining that the discovery of the fact that the earth had a new satellite coincident with the receipt of the mysterious messages was evidence that the new planetoid was inhabited and that the messages were attempts on the part of the inhabitants to communicate with us.

[222] The fact that the messages were on a lower wave length than any receiver then in existence could receive with any degree of clarity, and the additional fact that they appeared to come from an immense distance lent a certain air of plausibility to these ebullitions in the Sunday magazine sections. For some weeks the feature writers harped on the subject, but the hurried construction of new receivers which would work on a lower wave length yielded no results, and the solemn pronouncements of astronomers to the effect that the new celestial body could by no possibility have an atmosphere on account of its small size finally put an end to the talk. So the matter lapsed into oblivion.

While quite a few people will remember the two events I have noted, I doubt whether there are five hundred people alive who will remember anything at all about the disappearance of Dr. Livermore of the University of Calvada on September twenty-third. He was a man of some local prominence, but he had no more than a local fame, and few papers outside of California even noted the event in their columns. I do not think that anyone ever tried to connect up his disappearance with the radio messages or the discovery of the new earthly satellite; yet the three events were closely bound up together, and but for the Doctor's disappearance, the other two would never have happened.

Dr. Livermore taught physics at Calvada, or at least he taught the subject when he remembered that he had a class and felt like teaching. His students never knew whether he would appear at class or not; but he always passed everyone who took his courses and so, of course, they were always crowded. The University authorities used to remonstrate with him, but his ability as a research worker was so well known and recognized that he was allowed to go about as he pleased. He was a bachelor who lived alone and who had no interests in life, so far as anyone knew, other than his work.

I first made contact with him when I was a freshman at Calvada, and for some unknown reason he took a liking to me. My father had insisted that I follow in his footsteps as an electrical engineer; as he was paying my bills, I had to make a show at studying engineering while I clandestinely pursued my hobby, literature. Dr. Livermore's courses were the easiest in the school and they counted as science, so I regularly registered for them, cut them, and attended a class in literature as an auditor. The Doctor used to meet me on the campus and laughingly scold me for my absence, but he was really in sympathy with my ambition and he regularly gave me a passing mark and my units of credit without regard to my attendance, or, rather, lack of it.

When I graduated from Calvada I was theoretically an electrical engineer. Practically I had a pretty good knowledge of contemporary literature and knew almost nothing about my so-called profession. I stalled around Dad's office for a few months until I landed a job as a cub reporter on the San Francisco Graphic and then I quit him cold. When the storm blew over, Dad admitted that you couldn't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear and agreed with a grunt to my new line of work. He said that I would probably be a better reporter than an engineer because I couldn't by any possibility be a worse one, and let it go at that. However, all this has nothing to do with the story. It just explains how I came to be acquainted with Dr. Livermore, in the first place, and why he sent for me on September twenty-second, in the second place.

The morning of the twenty-second the City Editor called me in and asked me if I knew "Old Liverpills."

"He says that he has a good story ready to break but he won't talk to anyone but you," went on Barnes. "I of[223]fered to send out a good man, for when Old Liverpills starts a story it ought to be good, but all I got was a high powered bawling out. He said that he would talk to you or no one and would just as soon talk to no one as to me any longer. Then he hung up. You'd better take a run out to Calvada and see what he has to say. I can have a good man rewrite your drivel when you get back."

I was more or less used to that sort of talk from Barnes so I paid no attention to it. I drove my flivver down to Calvada and asked for the Doctor.

"Dr. Livermore?" said the bursar. "Why, he hasn't been around here for the last ten months. This is his sabbatical year and he is spending it on a ranch he owns up at Hat Creek, near Mount Lassen. You'll have to go there if you want to see him."

I knew better than to report back to Barnes without the story, so there was nothing to it but to drive up to Hat Creek, and a long, hard drive it was. I made Redding late that night; the next day I drove on to Burney and asked for directions to the Doctor's ranch.

"So you're going up to Doc Livermore's, are you?" asked the Postmaster, my informant. "Have you got an invitation?"

I assured him that I had.

"It's a good thing," he replied, "because he don't allow anyone on his place without one. I'd like to go up there myself and see what's going on, but I don't want to get shot at like old Pete Johnson did when he tried to drop in on the Doc and pay him a little call. There's something mighty funny going on up there."

Naturally I tried to find out what was going on but evidently the Postmaster, who was also the express agent, didn't know. All he could tell me was that a "lot of junk" had come for the Doctor by express and that a lot more had been hauled in by truck from Redding.

"What kind of junk?" I asked him.

"Almost everything, Bub: sheet steel, machinery, batteries, cases of glass, and Lord knows what all. It's been going on ever since he landed there. He has a bunch of Indians working for him and he don't let a white man on the place."

Forced to be satisfied with this meager information, I started old Lizzie and lit out for the ranch. After I had turned off the main trail I met no one until the ranch house was in sight. As I rounded a bend in the road which brought me in sight of the building, I was forced to put on my brakes at top speed to avoid running into a chain which was stretched across the road. An Indian armed with a Winchester rifle stood behind it, and when I stopped he came up and asked my business.

"My business is with Dr. Livermore," I said tartly.

"You got letter?" he inquired.

"No," I answered.

"No ketchum letter, no ketchum Doctor," he replied, and walked stolidly back to his post.

"This is absurd," I shouted, and drove Lizzie up to the chain. I saw that it was merely hooked to a ring at the end, and I climbed out and started to take it down. A thirty-thirty bullet embedded itself in the post an inch or two from my head, and I changed my mind about taking down that chain.

"No ketchum letter, no ketchum Doctor," said the Indian laconically as he pumped another shell into his gun.

I was balked, until I noticed a pair of telephone wires running from the house to the tree to which one end of the chain was fastened.

"Is that a telephone to the house?" I demanded.

The Indian grunted an assent.

"Dr. Livermore telephoned me to come and see him," I said. "Can't I call him up and see if he still wants to see me?"

[224] The Indian debated the question with himself for a minute and then nodded a doubtful assent. I cranked the old coffee mill type of telephone which I found, and presently heard the voice of Dr. Livermore.

"This is Tom Faber, Doctor," I said. "The Graphic sent me up to get a story from you, but there's an Indian here who started to murder me when I tried to get past your barricade."

"Good for him," chuckled the Doctor. "I heard the shot, but didn't know that he was shooting at you. Tell him to talk to me."

The Indian took the telephone at my bidding and listened for a minute.

"You go in," he agreed when he hung up the receiver.

He took down the chain and I drove on up to the house, to find the Doctor waiting for me on the veranda.

"Hello, Tom," he greeted me heartily. "So you had trouble with my guard, did you?"

"I nearly got murdered," I said ruefully.

"I expect that Joe would have drilled you if you had tried to force your way in," he remarked cheerfully. "I forgot to tell him that you were coming to-day. I told him you would be here yesterday, but yesterday isn't to-day to that Indian. I wasn't sure you would get here at all, in

Comments (0)