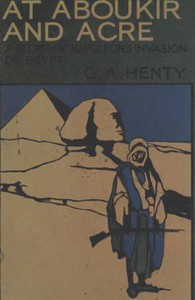

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt by G. A. Henty (free novels to read txt) 📗

- Author: G. A. Henty

Book online «At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt by G. A. Henty (free novels to read txt) 📗». Author G. A. Henty

"I am not crying for joy that I am freed, brother," he said, "but with pleasure at seeing you alive. When we got to the end of that street and saw, for the first time, that you were not with us, and, looking back, could see that your horse had fallen, we gave you up for dead, and bitterly did my father reproach himself for having permitted you to share in our attack. He is among the dead, brother; I saw him fall. I had been separated from him by the rush of the French horsemen, but I saw him fighting desperately, until at last struck down. Then, almost mad, I struck wildly. I felt a heavy blow on my head, and should have fallen had not a French soldier seized my arm and dragged me across his saddle in front of him. I was dimly conscious of being handed over to the infantry, and placed with some other prisoners. I sank down, and should have bled to death had not an Arab among them bandaged my head. The fight was nearly over then, and I was brought up here."

"I can give you good news, Sidi. I went last night with the two men whom we had left behind, and searched for some hours among the dead for you and your father, and found him at last. He was insensible, but not dead. We carried him off, and the other two are with him in a grove six miles away, and I have every hope that he will recover. He has five or six wounds, but I do not think that any of them are mortal."

Sidi fairly broke down on hearing the news, and nothing further was said until they had issued from the gate. The officer was still there who had spoken to Edgar on entering.

"So you have saved your friend?" he said pleasantly, as Edgar passed. "He is lucky, for I fancy he will be the[Pg 129] only one of the Arabs who will issue out of here to-day."

"I thank you much, monsieur, for having let me pass," Edgar said gratefully. "I feared so much that I should not be allowed to enter to speak for him."

The officer nodded, and the two lads went out. They had gone but a hundred yards when Sidi said:

"I must sit down for a while, Edgar. I have eaten nothing since yesterday morning, and I have lost much blood, and all this happiness is too much for me. Don't think me very childish."

"I don't think you so at all, Sidi. It has been a fearful time, and I don't wonder that you are upset. Look, there is a quiet spot between those two huts. Do you sit down there; you can't go on as you are. In the first place, your dress is covered with blood; and in the next, you are too weak to walk. I will go into the town. There are plenty of shops close to the gate, and I will buy a burnoose that will cover you, and a change of clothes for you to make afterwards. I will get you some food and a little cordial."

Sidi shook his head.

"Nonsense, man!" Edgar went on. "This is medicine, not wine, and you must take something of the sort or you won't be fit to travel. I shall get some fellah's clothes for myself, a basket of food and other things to take out to your father, and I will hire a couple of donkeys. You are no more fit to walk six miles than you are to fly, and I feel rather shaky myself. I sha'n't be away more than half an hour."

After seeing Sidi seated in the place he had indicated, where he would not be seen by those passing on the road, Edgar at once went in through the gate. The provisions,[Pg 130] and two or three bottles of good wine, were quickly purchased, but it took him some little time getting the clothes, for had he not bargained in the usual way, it would have seemed strange. As it was, the man of whom he purchased them congratulated himself on having made the best bargain that he had done for many a day. He bought two Arab suits, and two such as were worn by peasants, and a brown burnoose for Sidi to put on at once. Then, going out with the provision-basket and the clothes in a bundle, he went to the gate again, chose a couple of donkeys from those standing there for hire, and went along the road for a short distance. Telling the donkey-boy to wait with the animals until his return, he took the basket and the burnoose, which had been made up into a separate parcel, and went to the spot where he had left Sidi, who rose to his feet as he reached him.

"I am better now, and can go on."

"You are not going on until you have made a meal anyhow," Edgar replied; "and I feel hungry myself, for I have been up a good many hours."

Sidi sat down again. The basket was opened, and Edgar produced some bread and some cold kabobs (kabobs being small pieces of meat stuck on a skewer). Sidi eat some bread and fresh fruit, but he shook his head at the meat.

"I shall do better without it," he said. "Meat is for the strong. My wound will heal all the faster without it."

He did, however, drink from a tumbler Edgar had brought with him a small quantity of wine mixed with the water.

"I regard you as my hakim, and take this as medicine because you order it."

"I feel sure that the Prophet himself would not have forbidden it when so used. You look better already, and there is a little colour in your cheek. Now, let us be off.[Pg 131] If your father has recovered consciousness, he must be in great anxiety about you."

"But I want to ask you about yourself?"

"I will tell you when we are mounted. The sooner we are off the better."

He was glad to see that, as they walked towards the donkeys, Sidi stepped out much more firmly than before. He had put on his burnoose as soon as Edgar joined him, and this concealed him almost to his feet when he had mounted.

"We are not pressed for time," Edgar said to the donkey-boy. "Go along gently and quietly."

The donkey started at the easy trot that distinguishes his species in Egypt.

"Now, Edgar," Sidi said, as soon as they were in motion, "here have you been telling me about my father, and I have been telling you about myself, but not one word as yet have you told as to how you escaped, and so saved the lives of both of us. Allah has, assuredly, sent you to be our good genius, to aid us when we are in trouble, and to risk your life for ours."

"Well, never mind about that now, Sidi. I will tell you all about it; but it is a good long story."

So saying, he narrated his adventures in detail, from the time when his horse fell with him to the moment when he entered the room where the court-martial was being held. He made the story a long one, in order to prevent his friend from talking, for he saw when he had spoken how great was his emotion. He made his narrative last until they came within a quarter of a mile of the village near which the sheik was hidden.

"Now we will get off," he said, "and send the donkeys back."[Pg 132]

He paid the amount for which he had bargained for the animals, and bestowed a tip upon the boy that made him open his eyes with delight. They turned off from the road at once, made a detour, and came down upon the clump of trees from the other side. The Arabs had seen them approaching, and welcomed Sidi with exuberant delight. To his first question, "How is my father?" they said, "He is better. He is very weak. He has spoken but once. He looked round, evidently wondering where he was, and we told him how the young Englishman, his friend, had come to us, and how we had searched for hours among the dead, and, at last finding him, had carried him off. Then he said, 'Did you find my son?' We told him no, and that we had searched so carefully that we felt sure that he was not among the dead, but that you had gone back to the town to try and learn something about him. He shook his head a little, and then closed his eyes. He has not spoken again."

"Doubtless he feels sure, as we could not find you, that you are dead, Sidi. I have no doubt the sight of you will do him a great deal of good. I will go forward and let him know that you are here. Do not show yourself until I call you."

The sheik was lying with his eyes shut. As Edgar approached he opened them, and the lad saw he was recognized.

"Glad am I to see you conscious again, sheik," he said, bending over him.

The sheik feebly returned the pressure of his hand.

"May Allah pour his blessings upon you!" he whispered. "I am glad that I shall lie under the sands of the desert, and not be buried like a dog in a pit with others."

"I hope that you are not going to die, sheik. You are sorely weak from loss of blood, and you are wounded in[Pg 133] five places, but I think not at all that any of them are mortal."

"I care not to live," the sheik murmured. "Half my followers are dead. I mourn not for them; they, like myself, died in doing their duty and in fighting the Franks—but it is my boy, of whom I was so proud. I ought not to have taken him with me. Think you that I could wish to live, and go back to tell his mother that I took him to his death."

"He was not killed, sheik; we assured ourselves of that before we carried you away, and I found that, with twenty other Arabs and two or three hundred of the townsmen, he was taken prisoner to the citadel."

A look of pain passed across the sheik's face.

"Your news is not good; it is bad," he said, with more energy than he had hitherto shown. "It were better had he died in battle than be shot in cold blood. Think you that they will spare any whom they caught in arms against them?"

"My news is good, sheik," Edgar said calmly; "had it been otherwise I would have left you to think that he had died on the field of battle. I have reason to believe that Sidi has been released, and that you will soon see him."

For a moment the sheik's eyes expressed incredulity; then the assured tone and the calm manner of Edgar convinced him that he at least believed that it was true.

"Are you sure, are you quite sure?" he asked, in tones so low that Edgar could scarce hear him.

"I am quite sure—I would not buoy you up with false hopes. Sidi is free. He is not far off now, and will speedily be here, directly he knows that you are strong enough to see him."

For a minute the sheik's eyes closed, his lips moved, but[Pg 134] no sound came from them, but Edgar knew that he was murmuring thanks to Allah for his son's preservation. Then he looked up again.

"I am strong enough," he said; "your news has made a man of me again. Send him here."

Edgar walked away and joined Sidi.

"Be very calm and quiet," he said; "your father is very, very weak. Do not break down. He knows that you are close by, and is prepared to see you. Do not, I beg of you, agitate him; do not let him talk, or talk much yourself; be calm and restful with him."

He turned away and walked to the end of the trees, where he engaged in a short conversation with the two Arabs. Then he turned again, and went near enough to catch a sight of the sheik. Sidi was kneeling by his side, holding his hand to his heart, and a smile of happiness illuminated the drawn face of the wounded man. Satisfied that all was going on well, he joined the men.

"In the basket you will find a small cooking-pot," he said. "Pick up some of the driest sticks that you can find, so as not to make

Comments (0)