Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗

- Author: Charles Dickens

Book online «Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗». Author Charles Dickens

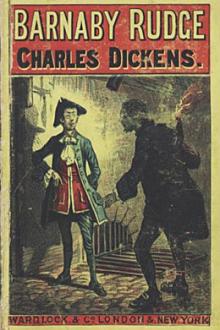

‘Except,’ said Gabriel, bending down yet more, and looking cautiously towards their silent neighhour, ‘except in respect of the robber himself. What like was he, sir? Speak low, if you please. Barnaby means no harm, but I have watched him oftener than you, and I know, little as you would think it, that he’s listening now.’

It required a strong confidence in the locksmith’s veracity to lead any one to this belief, for every sense and faculty that Barnaby possessed, seemed to be fixed upon his game, to the exclusion of all other things. Something in the young man’s face expressed this opinion, for Gabriel repeated what he had just said, more earnestly than before, and with another glance towards Barnaby, again asked what like the man was.

‘The night was so dark,’ said Edward, ‘the attack so sudden, and he so wrapped and muffled up, that I can hardly say. It seems that—’

‘Don’t mention his name, sir,’ returned the locksmith, following his look towards Barnaby; ‘I know HE saw him. I want to know what YOU saw.’

‘All I remember is,’ said Edward, ‘that as he checked his horse his hat was blown off. He caught it, and replaced it on his head, which I observed was bound with a dark handkerchief. A stranger entered the Maypole while I was there, whom I had not seen—for I had sat apart for reasons of my own—and when I rose to leave the room and glanced round, he was in the shadow of the chimney and hidden from my sight. But, if he and the robber were two different persons, their voices were strangely and most remarkably alike; for directly the man addressed me in the road, I recognised his speech again.’

‘It is as I feared. The very man was here to-night,’ thought the locksmith, changing colour. ‘What dark history is this!’

‘Halloa!’ cried a hoarse voice in his ear. ‘Halloa, halloa, halloa! Bow wow wow. What’s the matter here! Hal-loa!’

The speaker—who made the locksmith start as if he had been some supernatural agent—was a large raven, who had perched upon the top of the easy-chair, unseen by him and Edward, and listened with a polite attention and a most extraordinary appearance of comprehending every word, to all they had said up to this point; turning his head from one to the other, as if his office were to judge between them, and it were of the very last importance that he should not lose a word.

‘Look at him!’ said Varden, divided between admiration of the bird and a kind of fear of him. ‘Was there ever such a knowing imp as that! Oh he’s a dreadful fellow!’

The raven, with his head very much on one side, and his bright eye shining like a diamond, preserved a thoughtful silence for a few seconds, and then replied in a voice so hoarse and distant, that it seemed to come through his thick feathers rather than out of his mouth.

‘Halloa, halloa, halloa! What’s the matter here! Keep up your spirits. Never say die. Bow wow wow. I’m a devil, I’m a devil, I’m a devil. Hurrah!’—And then, as if exulting in his infernal character, he began to whistle.

‘I more than half believe he speaks the truth. Upon my word I do,’ said Varden. ‘Do you see how he looks at me, as if he knew what I was saying?’

To which the bird, balancing himself on tiptoe, as it were, and moving his body up and down in a sort of grave dance, rejoined, ‘I’m a devil, I’m a devil, I’m a devil,’ and flapped his wings against his sides as if he were bursting with laughter. Barnaby clapped his hands, and fairly rolled upon the ground in an ecstasy of delight.

‘Strange companions, sir,’ said the locksmith, shaking his head, and looking from one to the other. ‘The bird has all the wit.’

‘Strange indeed!’ said Edward, holding out his forefinger to the raven, who, in acknowledgment of the attention, made a dive at it immediately with his iron bill. ‘Is he old?’

‘A mere boy, sir,’ replied the locksmith. ‘A hundred and twenty, or thereabouts. Call him down, Barnaby, my man.’

‘Call him!’ echoed Barnaby, sitting upright upon the floor, and staring vacantly at Gabriel, as he thrust his hair back from his face. ‘But who can make him come! He calls me, and makes me go where he will. He goes on before, and I follow. He’s the master, and I’m the man. Is that the truth, Grip?’

The raven gave a short, comfortable, confidential kind of croak;—a most expressive croak, which seemed to say, ‘You needn’t let these fellows into our secrets. We understand each other. It’s all right.’

‘I make HIM come?’ cried Barnaby, pointing to the bird. ‘Him, who never goes to sleep, or so much as winks!—Why, any time of night, you may see his eyes in my dark room, shining like two sparks. And every night, and all night too, he’s broad awake, talking to himself, thinking what he shall do to-morrow, where we shall go, and what he shall steal, and hide, and bury. I make HIM come! Ha ha ha!’

On second thoughts, the bird appeared disposed to come of himself. After a short survey of the ground, and a few sidelong looks at the ceiling and at everybody present in turn, he fluttered to the floor, and went to Barnaby—not in a hop, or walk, or run, but in a pace like that of a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles. Then, stepping into his extended hand, and condescending to be held out at arm’s length, he gave vent to a succession of sounds, not unlike the drawing of some eight or ten dozen of long corks, and again asserted his brimstone birth and parentage with great distinctness.

The locksmith shook his head—perhaps in some doubt of the creature’s being really nothing but a bird—perhaps in pity for Barnaby, who by this time had him in his arms, and was rolling about, with him, on the ground. As he raised his eyes from the poor fellow he encountered those of his mother, who had entered the room, and was looking on in silence.

She was quite white in the face, even to her lips, but had wholly subdued her emotion, and wore her usual quiet look. Varden fancied as he glanced at her that she shrunk from his eye; and that she busied herself about the wounded gentleman to avoid him the better.

It was time he went to bed, she said. He was to be removed to his own home on the morrow, and he had already exceeded his time for sitting up, by a full hour. Acting on this hint, the locksmith prepared to take his leave.

‘By the bye,’ said Edward, as he shook him by the hand, and looked from him to Mrs Rudge and back again, ‘what noise was

Comments (0)