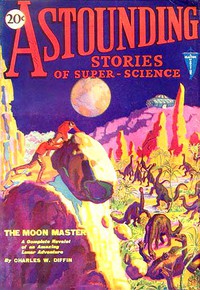

Two Thousand Miles Below by Charles Willard Diffin (whitelam books TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Willard Diffin

Book online «Two Thousand Miles Below by Charles Willard Diffin (whitelam books TXT) 📗». Author Charles Willard Diffin

"That, too, I will explain later. It is simple; even the Dwellers in the Dark—those whom you call the mole-men—have Oro and Grah to serve them."

or launched into a long account of their tribal legends, of that time in the long ago when an angry sun god had driven his children inside the earth; of how Gor, and the son of Gor, and his son's sons tried always to return.

Rawson was listening only subconsciously. They were circling the white mountain, ascending its lower slope. Now he could see beyond it as far as the land extended, and he was startled to find this distance so short. They were on an island, ten miles or so in length, and beyond it was the sea; he must ask Gor about that.

"It is all that is left," said Gor, when Rawson interrupted his narrative. "Once the land was great and the sea small—this also in the long ago—but always it has risen. The air we breathe and the water in the sea come from the central sun. The air rushes out, as you know; the water has no place to retreat."

Again he took up his tale, but Rawson's eyes were following the upward curve of that sea. They, seemed to be in the bottom of a great bowl; he was trying to estimate, trying to gage distance.

"... and so, after many generations had lived and died, they found the Pathway to the Light," Gor was saying. "It is our name for the shaft through which you came. This was thousands of your years ago, when he who was then Gor, and the bravest of the tribe, descended. Even then they were workers in metal and they knew of Oro and Grah. They were our fathers, the first People of the Light."

awson had a question ready on his tongue, but Gor's words suggested another. "That shaft," he said, "the Pathway to the Light—do you mean it extends clear up to the mole-men's world? Why don't they come down?"

"To them the way is lost; the Pathway is closed above the zone of fire. That other Gor did that. And those who remained—the mole-men—have forgotten. They could break their way through if they knew—they are master-workers with fire—but for them the Pathway ends, and below is the great heat. But we know of a way around the closed place, the hidden way to the great Lake of Fire."

"They could break their way through if they knew!" repeated Rawson softly. For an instant he stood silent and unbreathing; he was remembering the ugly eyes in a priest's hideous face. The eyes were watching him as the White Ones took him away.

He forced his thoughts to come back to the earlier question. "What," he asked, "is the diameter, the distance across the inside world? How far is it from here to your sun? How many miles?"

"Miles?" questioned Gor. "We know the word, for the Mountain has told us, but the length of a mile we could not know. This I can say: there were wise men in the past when our own world was larger. They worked magic with little marks on paper. It is said that they knew that if one came here from our sun and kept on as far again through the solid rock, he would reach the outside—the land, of the true sun, from which our forefathers came."

Rawson nodded his head, while his eyes followed that sweeping green bowl of the sea. "Not far off," he said abstractedly. "Two thousand miles radius—and the earth itself not a solid ball, but a big globular shell two thousand miles thick. I could rig up a level, I suppose; work out an approximation of the curvature."

From the smooth winding path which they had followed there sounded behind them hurrying footsteps; a moment later Loah stood beside him.

er eyes gave unmistakable corroboration of what Gor had said of that torrent of tears, but she looked at Dean bravely, while every show of emotion was erased from her face. "You sent for me," she said.

And Rawson, though now he knew he could speak to her and be understood, found himself at a loss for words.

"We wanted you with us, Gor and I," he began, then paused. She was so different from the girl whose smiling eyes had welcomed him. The change had come when he spoke those first words on his arrival, and now she was so coldly impersonal.

"I wanted to thank you. You saved my life; you were so brave, so...." Again he hesitated; he wanted to tell her how dear, how utterly lovely, she had seemed.

"It was nothing; it has pleased me to do it," she said quietly, then walked on ahead while the others followed. But Rawson knew that that slim body was tense with repressed emotion. He had not realized how he had looked forward to seeing again that welcoming light in her eyes. He was still puzzling over the change as they entered a natural cave in the mountainside.

A winding passage showed between sheer walls of snow white, where giant crystals had parted along their planes of cleavage. Then the passage grew dark, but he could see that ahead of them it opened to form a wider space. There were lights on the walls of the room, lights like the one that Loah had carried. And on the floor were rows of tables where men were busy at work, writing endlessly on long scrolls of parchment.

he Wise Ones," Gor was saying. "Servants of the Holy Mountain." Yet even then men knelt at Rawson's coming as had the other more humble people. They then returned to their tables, and in that crystal mountain was only the sound of their scratching pens and the faint sigh of a breeze that blew in through a hidden passage to furnish ventilation.

Yet there were some at those tables whose pens did not move; they seemed to be waiting expectantly. One of them spoke. "The time is near," he said. "Are the Servants prepared?"

And the waiting ones answered: "We are prepared."

Rawson glanced sharply about. "What hocus-pocus is this?" he was asking himself. Still the silence persisted. He looked at the waiting men, motionless, their heads bent, their hands ready above the parchment scrolls. He saw again the white walls, the single broad band of some glittering metal that made a continuous black stripe around walls and ceiling and floor.

"What kind of ore is that?" he was asking himself silently. "It's metallic; it runs right through the mountain. I wonder—"

His idle thoughts were never finished. A ripping crash like the crackle of lightning in the vaulted room! Then a voice—the mountain itself was speaking—speaking in words whose familiar accent brought a sob into his throat.

"Station K-twenty-two-A," said the voice of the mountain, "the super-power station of the Radio-news Service at Los Angeles, California."

t's tuned in!" gasped Rawson. "Tuned in on the big L. A. station! A gigantic crystal detector! Those heavy laminations of imbedded metal furnish the inductance." Then his incoherent words ended—the mountain was speaking.

"Radiopress dispatch: The invasion of the mole-men has not been checked. Army Air Force fought a terrific engagement about midnight, last night, and met defeat. Over one hundred fighting planes were brought down in flames. Even the new battle-plane type, the latest dreadnoughts of the air, succumbed.

"Heavy loss of life, although civilian population of three towns had been evacuated before the mole-men destroyed them. Gordon Smith is reported killed. Smith was associated with Dean Rawson in the Tonah Basin where the mole-men first appeared. With Colonel Culver of the California National Guard, Smith was returning from Washington in an Army dreadnought which crashed back of the enemy's lines."

Rawson's tanned face had gone white; he knew the others were looking at him curiously, all but the men at the tables whose pens were flying furiously across the waiting scrolls. Before him the face of Loah, suddenly wide-eyed and troubled, swam dizzily. He could scarcely see it—he was seeing other sights of another world.

"They're out," he half whispered. "The red devils are out—and Smithy—Smithy's gone!"

CHAPTER XX Taloned Handsimple, pastoral folk, the People of the Light! In their inner world, a vanishing world, where nearly all of what once had been a vast country was now covered by the steadily encroaching sea, they had resisted the degeneration which might easily have followed the destruction of a complex civilization. Living simply, and clean of mind, they had clung to the culture of the past as it was taught them by their Wise Ones. And now the People of the Light had found a new god.

Not that Dean Rawson had asked for that exalted position; on the contrary he had tried his best to make them understand that he was only one of many millions, some better, some worse, but all of them merely humans.

His speaking the language of the holy mountain had convinced them first. But when old Rotan, oldest and grayest of the mountain's servants, went into a trance, then Rawson could no longer escape the honors being thrust upon him.

"The time of deliverance is at hand," old Rotan said when he awoke. His voice that so long had been cracked and feeble was suddenly strong, vibrant with belief in the visions that had come to him.

They were in the inner chamber of the white mountain, where Dean Rawson, heartsick, lonely and hopeless, had spent most of his time listening to the voice from the outer world. Gor was there, and Loah; and the writers had left their desks to gather around old Rotan, where now the old servant of the mountain stood erect, his glistening eyes fixed unwaveringly upon Rawson.

"Listen," he commanded. "Rotan speaks the truth. Never shall the People of the Light return to the outer world; it is here we stay. For now our world which is lost shall be returned to us." His eyes, unnaturally bright, met the wondering gaze of his own people gathered around, then came back to rest again upon Rawson.

ean—Rah—Sun!" he said. "'Rah'—do you not see? It is our own word, Rah—the Messenger! Dean—Messenger of the Sun! The sun-god has sent him—he will set us free. He will restore our lost cities. The People of the Light will spread out to fill the new land; they will multiply, and once more will be a mighty nation, living happily as of old in their own lost world.

"Dean!" he called. "Dean—Messenger of the Sun!" He was drawn to his full frail height, his arms outstretched. But Rawson saw the old eyes close, sensed the first slackening of that tense body; it was he who sprang and caught the sagging figure in his arms, then lowered the lifeless body to the floor of crystal white.

Even happiness can kill. A feeble heart can cease to beat under the stress of emotions too beautiful to be borne. And Rotan, wisest of the wise, had passed on to serve his sun-god in another world.

And thereafter, Rawson, Dean-Rah-Sun, was undeniably a god. But he wondered, even then, while the others dropped to their knees in humble worship, why Loah, her eyes brimming over with tears, had broken suddenly into uncontrollable sobs and had rushed blindly, swiftly, from the room.

o Rawson the unwavering, simple faith of the White Ones was only an added misery. Rotan's vision was accepted by them unquestioningly; their adoring eyes followed Rawson wherever he went, while the children carpeted his path to the holy mountain with golden flowers.

And there Rawson would sit, cursing silently his own helplessness, while the voice of the mountain told of further devastation up above. His plans for leading a force against the mole-men were abandoned. On the island, all that was left of this inner world, were only some two thousand persons, men, women and children. And the children were few; the population had been rigorously kept down. Their present number was all that the island would support, though every possible foot of ground was tilled.

"Only a handful of them," Rawson admitted despondently, "and not a weapon of any sort. They've kept by themselves. Only Loah and a few of the others had enough curiosity and nerve to scout around where the mole-men live. She even understands their talk! Lord, what I'd give for a thousand like her, a thousand men with her nerve! Then, with weapons, and means of transportation...." But at

Comments (0)