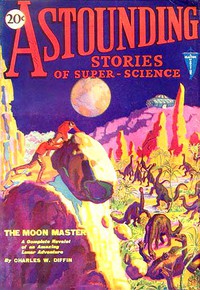

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 by Various (good romance books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 by Various (good romance books to read .TXT) 📗». Author Various

He had stood there for about an hour when suddenly there appeared in the sky above him, a meteor, a great disc of blue-white incandescence. It seemed to be rushing straight down toward him; instinctively he leaped back, as though to avoid the fiery missile.

As the constantly expanding disc flashed through the hundred miles of Earth's atmosphere, the ocean, as far as eye could see, became as light as day. Bathed in that baleful, white glare, Parkinson, bewildered, dazed, half-blinded, watched the approaching stellar visitant.

In a few moments it struck—no more than two miles away. In the last, bright flare of blue-white light, Parkinson saw a gigantic column of steam and boiling water leap up from the sea. Then thick, impenetrable darkness fell—darkness that was intensified by its contrast with the meteor's blinding light.

For ten tense, breathless seconds utter silence hung over the sea ... then, for those on the yacht, the world went mad! A shrill, unearthly shriek—the sound of the meteor's passage through the atmosphere; an ear-splitting roar, as of the simultaneous release of the thunder-drums of ages; a howling demon of wind; a solid wall of raging, swirling water of immeasurable height—all united in an indescribable chaos that bewildered those on board the Diana, and that lifted the yacht and—threw it upon its side!

When the first rushing mountain of lathering, thundering water crashed upon the yacht, Parkinson felt himself hurtling through the roaring air. For a moment he heard the infernal pandemonium of noise ... then the strangling, irresistible brine closed over his head.

A blackness deeper than that of the night—and Parkinson knew no more....

lowly consciousness returned to the bacteriologist. It came under the guise of a dull, yet penetrating throbbing coming from beneath the surface on which he lay. Vaguely he wondered at it; he had not yet entirely cast off the enshrouding stupor that gripped him.

Gradually he came into full possession of his faculties—and became aware of a dull aching throughout his entire body. In his chest it seemed to be intensified; every breath caused a sharp pang of pain.

Faltering and uncertain, he arose and peered around. Before, lay the open sea, calm now, and peaceful. Long, rolling swell swept in and dashed themselves against the rocks a few feet away. Rocks? For a moment Parkinson stared at the irregular shore-line in dazed wonder. Then as his mind cleared, the strangeness of his position flashed upon him.[217]

Solid earth was under his feet! Although he must be hundreds of miles from shore, in some way he had drifted upon land. So far as he knew, there were no islands in that part of the Atlantic; yet his very position belied the truth. He could not have drifted to the mainland; the fact that he was alive precluded all possibilities of that, for he would have drowned in far less time than the latter thought implied.

He turned and inspected the land upon which he had been cast. A small, barren island, bleak and inhospitable, and strangely metallic, met his gaze. The rays of the sun beating down upon it were thrown back with an uncomfortable intensity; the substance of the island was a lustrous, copperlike metal. No soil softened the harshness of the surface; indescribably rugged and pitted was the two hundred-foot expanse. It reminded Parkinson of a bronze relief-map of the moon.

For a moment he puzzled over the strangeness of the unnatural island; then suddenly he realized the truth. This was the meteor! Obviously, this was the upper side of the great sphere from space, protruding above the sea.

ortunate for him that the meteor had not been completely covered by water, he thought—but was it fortunate? True, he was alive now, thanks to the tiny island, but how long would he remain alive without food or water, and without hope of securing either? Unless he would be picked up by a passing steamer, he would die a far more unpleasant death than that of drowning. Some miracle had saved him from a watery grave; it would require another to rescue him from a worse fate.

Even now he was beginning to feel thirsty. He had no way of determining how long he had been unconscious, but that it was at least ten hours, he was certain, for the sun had been at its zenith when he had awakened. No less than fifteen hours had gone by since water—other than that of the sea—had passed his lips. And the fact that it was impossible for him to quench his thirst only served to render it more acute.

In order to take his mind from thoughts of his thirst and of the immediate future, he rapidly circled the island. As he had expected, it was utterly barren. With shoulders drooping in despair he settled wearily to a seat on the jagged mass of metal high up on top of the meteor.

An expression of sudden interest lit up his face. For a second time he felt that particular throbbing, that strange pulsing beneath the surface of the meteor. But now it was far more noticeable than before. It seemed to be directly below him, and very close to the surface.

Parkinson could not tell how long he sat there, but from the appearance of the sun, he thought that at the very shortest, an hour passed by while he remained on that spot. And during that time, the throbbing gradually increased until the metal began vibrating under his feet.

Suddenly the bacteriologist leaped aside. The vibrating had reached its height, and the meteor seemed to lurch, to tilt at a sharp angle. His leap carried him to firm footing again. And then, his thirst and hopeless position completely forgotten, Parkinson stared in fascination at the amazing spectacle before him.

n eighteen-foot disc of metal, a perfect circle, seemed to have been cut out of the top of the meteor. While he watched, it began turning slowly, ponderously, and started sinking into the meteor. As it sank, Parkinson fancied that it grew transparent, and gradually vanished into nothingness—but he wasn't sure.

A great pit, eighteen feet wide, but far deeper, lay before him in the very place where, not more than ten minutes before, he had stood. Not a moment too soon had he leaped.

Motionless he stood there, waiting in[218] tense expectation. What would happen next, he had not the least idea, but he couldn't prevent his imagination from running riot.

He hadn't long to wait before his watching was rewarded. A few minutes after the pit appeared, he heard a loud, high-pitched whir coming from the heart of the meteor. As it grew louder, it assumed a higher and still higher key, finally rising above the range of human ears. And at that moment the strange vehicle arose to the surface.

A simple-appearing mechanism was the car, consisting of a twelve-foot sphere of the same bronze-like metal that made up the meteor, with a huge wheel, like a bronze cincture, around its middle. It was the whirling of this great wheel that had caused the high-pitched whirring. The entire, strange machine was surrounded by a peculiar green radiance, a radiance that seemed to crackle ominously as the sphere hovered over the mouth of the pit.

For a moment the car hung motionless, then it drifted slowly to the surface of the meteor, landing a few feet away from Parkinson. Hastily he drew back from the greenly phosphorescent thing—but not before he had experienced an unpleasant prickling sensation over his entire body.

As the bacteriologist drew away, there was a sharp, audible click within the interior of the sphere; and the green radiance vanished. At the same moment, three heavy metal supports sprang from equi-distant points in the sides of the car, and held the sphere in a balanced position on the rounded top of the meteor.

There was a soft, grating sound on the opposite side of the car. Quickly, Parkinson circled it—and stopped short in surprise.

en were descending from an opening in the side of the sphere! Parkinson had reasoned that since the meteor had come from the depths of space, any being in its interior, unnatural as that seemed, would have assumed a form quite different from the human. Of course, conditions on Earth could be approximated on another planet. At any rate, whatever the explanation, the sphere was emitting men!

They were men—but there was something queer about them. They were very tall—seven feet or more—and very thin; and their skins were a delicate, transparent white. They looked rather ghostly in their tight-fitting white suits. It was not this that made them seem queer, however: it was an indefinite something, a vague suggestion of heartless inhumanity, of unearthliness, that was somehow repulsive and loathsome.

There were three of them, all very similar in appearance and bearing. Their surprise at the sight of Parkinson, if anything, was greater than the start their appearance had given him. He, at least, had expected to see beings of some sort, while the three had been taken completely by surprise.

For a moment they surveyed him with staring, cold-blue eyes. Then Parkinson extended his hand, and as cordially as he could, exclaimed:

"Hello! Welcome to Earth!"

The visitors from space ignored his advances and continued staring at him. Their attitude at first was quizzical, speculative, but slowly a hostile expression crept into their eyes.

Suddenly, with what seemed like common consent, they faced each other, and conversed in low tones in some unintelligible tongue. For almost a minute they talked, while Parkinson watched them in growing apprehension.

Finally they seemed to have reached some definite conclusion; with one accord they turned and moved slowly toward the bacteriologist, something distinctly menacing in their attitudes. The men from the meteor were tall, but they were thin; Parkinson, too, was large, and his six-foot length was covered with layers of solid muscle. As[219] the three advanced toward him, he doubled his fists, and crouched in readiness for the expected attack.

hey were almost upon him when he leaped into action. A crushing left to his stomach sent the first one to the meteor-top, where he lay doubled up in pain. But that was the only blow that Parkinson struck; in a moment he found himself lying prone upon his back, utterly helpless, his body completely paralyzed. What they had done to him, he did not know; all that he could remember was two thin bodies twining themselves around him—a sharp twinge of pain at the base of his skull; then absolute helplessness.

One of the tall beings grasped Parkinson about the waist, and with surprising strength, threw him over his shoulder. The other assisted his groaning fellow. When the latter had recovered to some extent, the three ascended the ladder that led into the metal sphere.

The interior of the strange vehicle, as far as Parkinson could see, was as simple as its exterior. There was no intricate machinery of any sort in the square room; probably what machinery there was lay between the interior and exterior walls of the sphere. As for controls, these consisted of several hundred little buttons that studded one of the walls.

When they entered the vehicle, Parkinson was literally, and none too gently, dumped upon the floor. The man who had carried him stepped over to the controls. Like those of a skilled typist, his long, thin fingers darted over the buttons. In a moment the sphere was in motion.

There were no more thrills for Parkinson in that ride than he would have derived from a similar ride in an elevator. They sank very slowly for some minutes, it seemed to him; then they stopped with a barely noticeable jar.

The door of the car was thrust aside by one of the three, and Parkinson was borne from the sphere. A bright, coppery light flooded the interior of the meteor, seeming to radiate from its walls. In his helpless state, and in the awkward position in which he was carried, with his head close to the floor, he could see little of the room through which they passed, in spite of the light. Later, however, he learned that it was circular in shape, and about twice the diameter of the cylindrical tube that led into it. The wall that bound this chamber was broken at regular intervals by tall, narrow, doorways, each leading into a different room.

Parkinson was carried into one of these, and was placed in a high-backed metal chair. After

Comments (0)