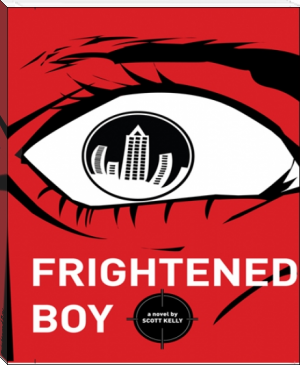

Frightened Boy - Scott Kelly (ebook reader with android os .txt) 📗

- Author: Scott Kelly

Book online «Frightened Boy - Scott Kelly (ebook reader with android os .txt) 📗». Author Scott Kelly

“Tell me about your parents,” Escher said suddenly, cracking the silence several hours after we’d arrived.

“Who?” I asked. If Whisper heard, she didn’t bother to respond.

“You first,” he said to me.

“They were liberals. They hated this country and loved it at the same time.”

Escher nodded.

I loathed telling him the truth—they’d died cowards' deaths; they’d been cryogenically frozen in hopes of avoiding the Collapse everyone saw coming. Died in a goddamn power outage, like spoiled lunchmeat.

So I lied. “They were sent to Gitmo,” I said. It came easier than I expected. “I haven’t heard from them in a quarter of a century. They’re dead, I am sure.”

Escher only nodded again. “And you?” he asked Erika.

“My mom was a performance artist like me,” she said. “I never knew my dad.”

“You’re a performance artist?” Escher asked, his eyes widening. “All the world is but a stage, and we are but actors upon it. Truer words have never been said. They are words so true that no other words ever need be said after them, save for the sake of drama.”

Erika smiled for the first time that night. A pang of jealousy swept through me. I didn’t say a word though.

“Well, go on,” Escher told her.

“Performance art is true art,” Erika continued. “No pens, no paper, no instruments—just life. No roundabout way of showing people the way they should act. Throw away the pen and pad and become the poem, you know?”

“You’re a person after my own heart,” Escher said.

I watched Whisper as the two spoke. It seemed suddenly that she was very small and childlike. She pulled her hood up over her head and stroked the feline on her lap. I wondered what had happened to her parents, what had led her to lead this life. Escher didn’t seem to notice she existed. I wondered—did working with Escher mean she had to admit she was nothing but a figment of his imagination? Would Escher ever respect someone he didn’t believe was truly a person?

Erika continued: “Like I said, my mother was a performance artist to the end. She never had much, never had any respect or recognition—but she always put her art first, even when it came to her death.”

“How?” Escher asked.

“Six days before Halloween, while I was away with relatives, she hung herself in the front yard. For a week and a half, people walked by her house and up to the front door and right past her rotting corpse. Everyone thought she was just a Halloween decoration—an elaborate wax figure—put there to scare people. They didn’t cut her down until a neighbor came to complain about the smell and realized where it was coming from.”

There was a long pause. No one seemed to know what to say.

“That’s fucked up,” Escher spoke at last, chuckling a bit.

If Erika was offended by his flippant response, she didn’t show it. “What about you, tough guy?” she asked. I hated to hear her act the least bit curious about Escher. Somehow, it reminded me of all the things I wasn’t and he was.

He cleared his throat and looked down at the ground then straight up at the ceiling. He leaned back against the end of the gutted vehicle that was his bed. “I was painting a gateway, using a mathematical equation called Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem. That’s the last thing I remember. I’m probably lying in a hospital bed somewhere, in a coma, in the real world—or maybe I’m just passed out on the floor of my studio. I don’t know. I woke up here in this world a few years ago.”

“Where did you wake up?” I asked.

The Red King shook his head. “I don’t want to talk about it. Everything that happens around me is representative of something from my past reality. You are all just figments of my imagination. It’s useless for me to tell you, because you cannot understand and already know, anyway. I used to think I could just explain it, but it’s not that easy.”

*

I don’t remember going to sleep, only checking my watch intermittently throughout the night, always disappointed how little time passed. My mind dragged itself on hands and knees through the night. No one seemed to be sleeping but Escher and Whisper’s cats.

Shortly after dawn, Escher let out an enormous yawn, stretched his arms, and jumped to his feet out the side of the vehicle turned bed. He surveyed his dismal compatriots and clicked his tongue disapprovingly. “You’ve got to learn how to make yourselves sleep,” he told us. “You never know when and where you’ll be forced to take a nap.”

Whisper regained her same impenetrable posture, apparently recovered from whatever depression struck her the night before. Once more, she was the beautiful angel carved into a sixteenth-century church, the stoic maiden on the front of an ancient warship.

Escher continued to ignore her. In fact, it seemed Escher took Whisper’s presence entirely for granted when there were others about.

He made his way to the filthy, grime-covered sink in the corner of the shop and washed his face and hands. The water sputtered haltingly out the faucet in shifting shades of gray and brown.

Erika let out a soft “Gross.”

“Where are we going today?” I asked Escher.

“To a new base, where we’ll summon the Strangers,” he said.

“And then?” Erika asked.

“That’s enough questions, I think,” Escher said.

As we set out the door, Erika complained, “Do we have to walk?”

“No,” Escher said simply and then began walking away from city.

Erika stood impatiently, awaiting some further explanation, but none was offered. At last, she sighed and began jogging after him.

We stumbled across a long line of people in front of a makeshift grill. “Feed us,” Erika chimed from the rear of the party.

I was starving too. It’d been at least a full day since I’d eaten, but I wasn’t about to start complaining to our leaders.

When they turned a deaf ear to my perky, brunette disciple, she turned to me. “Bless me, Father,” she started, “with my daily bread. I am hungry, and I turn to you for food.” She trailed on into the Lord’s Prayer, but I was too uncomfortable to listen.

This got Escher’s attention. He stopped, turned around, and faced us. “What’s this?” he asked, an eyebrow raised in suspicion.

“It’s, uh…hard to explain,” I stammered.

“Try,” he commanded.

Erika stopped her prayer and stepped in front of me. “He’s God,” she said simply. “I worship him.”

“It’s…something she decided to do on her own,” I apologized.

“And I thought I was messed up,” Escher grinned. “What the hell inspired her to worship you?”

“Divine signs,” Erika said earnestly. “He appeared when I needed him most.”

“Does he answer your prayers?” Escher asked with a cruel tinge in his voice.

The subject seemed to attract his attention in a very unwelcome way. He probed into our strange relationship like he would an enemy combatant—like he had done with me that day in Tasumec Tower.

“Always,” Erika replied. “One way or another.”

“You know, there is a way of thinking—that to worship someone is to believe yourself to be a part of them. In other words, you might only be a figment in his imagination. Would you be willing to admit that?”

I reflexively took a step backwards.

“Absolut—”

“We’re wasting time,” Whisper interrupted. “There are more important things we could be doing. Let's eat and keep moving. We must not lose sight of the bigger picture.”

Escher raised his right arm and pointed at a man cooking some sort of meat over a metal bin. “Garsón!” he shouted. “Bring us your finest dish.”

The dirty man looked over at Escher then panicked and looked back to his food. He finally shook his head and picked a skewer up from the bin. A black, charred mass was curled pitifully around the thin metal pole.

Escher frowned but spied a fresh package of half-eaten bread beside the man. “Just the bread will do,” he said.

The man brought it over to Escher like a sailor walking down to the edge of a plank to retrieve a nickel. With each step he seemed to move slower and slower, more certain this was a trap.

Escher snatched the bread from him and handed it to Erika. “There,” he said. “I have fed you.”

I have never felt like a god, and in fact, the whole idea made me feel ridiculous and uncomfortable—but just then, I wished I could smite Escher.

We passed through commercial areas full of decayed mom-and-pops, practically fossils. We moved so far away from the center of Banlo Bay that we were neared Red Zones, completely uninhabitable for decades past, abandoned by the Fed, the State, and the City. The wild.

Our party reached the edge of the ruined commercial district until nothing but a line of tall, green pine trees rose up ahead. The trunks were thick, and the leafy coverage even thicker, so the ground beneath the trees was very dark and cool. I was struck by the stark contrast of this forest to the bleak urban landscape I was accustomed to, in which the only trees were very purposefully placed.

I realized we must have walked out of the city and into a land I’d sworn to myself I’d never return to. The suburbs. The real suburbs, too, not the tightly-packed neighborhoods I lived in; here, there were once golf courses, manmade lakes, and nature walks; space was as abundant as one’s imagination in using it. These suburbs, the satellite cities away from the heart of Banlo Bay, were the first to fall.

I looked over at Erika. Her eyes seemed equally enchanted by the forest. Even Escher seemed to relax. A smile crept onto his face as he led the march down the street, which had been steadily dissolving under our feet until now it was more of a gravel pathway than a road, leading us into the untamed woods.

14. Paradise

The suburb looked as though the foliage of the place declared war on everything man built there. Trees grew up out of the middle of roads; ivy covered everything. Street signs and lamps were so coated in plant life that they looked like Seussian trees. Most everywhere we walked, we had to be wary of tripping over the thick roots that ripped from the concrete like stitches in the earth.

“What is this place?” I asked.

“This is my paradise,” Escher said. “When Banlo Bay looks like this, maybe I’ll finally wake up.”

Whisper seemed at home as well. Where usually there were only one or two cats about her, they seemed more drawn to her now, and a trail of a dozen felines happily trotted after her.

We passed a public school that’d been eaten by ivy.

“This is what happens if you go a few decades without human intervention,” Whisper said. “Well, sort of. These plants were introduced by the city planners. They aren’t native. Without

Comments (0)