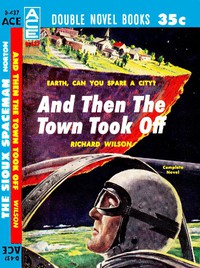

And Then the Town Took Off by Richard Wilson (books for 20 year olds .txt) 📗

- Author: Richard Wilson

Book online «And Then the Town Took Off by Richard Wilson (books for 20 year olds .txt) 📗». Author Richard Wilson

"Nope," Civek said. "No airport. No place for a plane to land, either."

"Maybe not a plane," Don said, "but a helicopter could land just about anywhere."

"No helicopters here, either."

"Maybe not. But I'll bet they're swarming all over you by morning."

"Hm," said Hector Civek. Don couldn't quite catch his expression in the rearview mirror. "I suppose they could, at that. Well, here's Cavalier. You go right in that door, where the others are going. There's Professor Garet. I've got to see him—excuse me."

The mayor was off across the campus. Don looked at Geneva Jervis, who was frowning. "Are you thinking," he asked, "that Mayor Civek was perhaps just a little less than completely honest with us?"

"I'm thinking," she said, "that I should have stayed with Aunt Hattie another night, then taken a plane to Washington."

"Washington?" Don said. "That's where I'm going. I mean where I was going before Superior became airborne. What do you do in Washington, Miss Jervis?"

"I work for the Government. Doesn't everybody?"

"Not everybody. Me, for instance."

"No?" she said. "Judging by that satchel you're handcuffed to, I'd have thought you were a courier for the Pentagon. Or maybe State."

He laughed quickly and loudly because she was getting uncomfortably close. "Oh, no. Nothing so glamorous. I'm a messenger for the Riggs National Bank, that's all. Where do you work?"

"I'm with Senator Bobby Thebold, S.O.B."

Don laughed again. "He sure is."

"Mister Cort!" she said, annoyed. "You know as well as I do that S.O.B. stands for Senate Office Building. I'm his secretary."

"I'm sorry. We'd better get out and find a place to sleep. It's getting late."

"Places to sleep," she corrected. She looked angry.

"Of course," Don said, puzzled by her emphasis. "Come on. Where they put you, you'll probably be surrounded by co-eds, even if I could get out of this cuff."

He took her bag in his free hand and they were met by a gray-haired woman who introduced herself as Mrs. Garet. "We'll try to make you comfortable," she said. "What a night, eh? The professor is simply beside himself. We haven't had so much excitement since the cosmolineator blew up."

They had a glimpse of the professor, still in his CD helmet, going around a corner, gesticulating wildly to someone wearing a white laboratory smock.

IIDon Cort had slept, but not well. He had tried to fold the brief case to pull it through his sleeve so he could take his coat off, but whatever was inside the brief case was too big. Cavalier had given him a room to himself at one end of a dormitory and he'd taken his pants off but had had to sleep with his coat and shirt on. He got up, feeling gritty, and did what little dressing was necessary.

It was eight o'clock, according to the watch on the unhandcuffed wrist, and things were going on. He had a view of the campus from his window. A bright sun shone on young people moving generally toward a squat building, and other people going in random directions. The first were students going to breakfast, he supposed, and the others were faculty members. The air was very clear and the long morning shadows distinct. Only then did he remember completely that he and the whole town of Superior were up in the air.

He went through the dormitory. A few students were still sleeping. The others had gone from their unmade beds. He shivered as he stepped outdoors. It was crisp, if not freezing, and his breath came out visibly. First he'd eat, he decided, so he'd be strong enough to go take a good look over the edge, in broad daylight, to the Earth below.

The mess hall, or whatever they called it, was cafeteria style and he got in line with a tray for juice, eggs and coffee. He saw no one he knew, but as he was looking for a table a willowy blonde girl smiled and gestured to the empty place opposite her.

"You're Mr. Cort," she said. "Won't you join me?"

"Thanks," he said, unloading his tray. "How did you know?"

"The mystery man with the handcuff. You'd be hard to miss. I'm Alis—that's A-l-i-s, not A-l-i-c-e—Garet. Are you with the FBI? Or did you escape from jail?"

"How do you do. No, just a bank messenger. What an unusual name. Professor Garet's daughter?"

"The same," she said. "Also the only. A pity, because if there'd been two of us I'd have had a fifty-fifty chance of going to OSU. As it is, I'm duty-bound to represent the second generation at the nut factory."

"Nut factory? You mean Cavalier?" Don struggled to manipulate knife and fork without knocking things off the table with his clinging brief case.

"Here, let me cut your eggs for you," Alis said. "You'd better order them scrambled tomorrow. Yes, Cavalier. Home of the crackpot theory and the latter-day alchemist."

"I'm sure it's not that bad. Thanks. As for tomorrow, I hope to be out of here by then."

"How do you get down from an elephant? Old riddle. You don't; you get down from ducks. How do you plan to get down from Superior?"

"I'll find a way. I'm more interested at the moment in how I got up here."

"You were levitated, like everybody else."

"You make it sound deliberate, Miss Garet, as if somebody hoisted a whole patch of real estate for some fell purpose."

"Scarcely fell, Mr. Cort. As for it being deliberate, that seems to be a matter of opinion. Apparently you haven't seen the papers."

"I didn't know there were any."

"Actually there's only one, the Superior Sentry, a weekly. This is an extra. Ed Clark must have been up all night getting it out." She opened her purse and unfolded a four-page tabloid.

Don blinked at the headline:

Town Gets High

"Ed Clark's something of an eccentric, like everybody else in Superior," Alis said.

Don read the story, which seemed to him a capricious treatment of an apparently grave situation.

Residents having business beyond the outskirts of town today are advised not to. It's a long way down. Where Superior was surrounded by Ohio, as usual, today Superior ends literally at the town line.

A Citizens' Emergency Fence-Building Committee is being formed, but in the meantime all are warned to stay well away from the edge. The law of gravity seems to have been repealed for the town but it is doubtful if the same exemption would apply to a dubious individual bent on investigating....

Don skimmed the rest. "I don't see anything about it being deliberate."

Alis had been creaming and sugaring Don's coffee. She pushed it across to him and said, "It's not on page one. Ed Clark and Mayor Civek don't get along, so you'll find the mayor's statement in a box on page three, bottom."

Don creased the paper the other way, took a sip of coffee, nodded his thanks, and read:

Mayor Claims Secession From Earth

Mayor Hector Civek, in a proclamation issued locally by hand and dropped to the rest of the world in a plastic shatter-proof bottle, said today that Superior has seceded from Earth. His reasons were as vague as his explanation.

The "reasons" include these: (1) Superior has been discriminated against by county, state and federal agencies; (2) Cavalier Institute has been held up to global derision by orthodox (presumably meaning accredited) colleges and universities; and (3) chicle exporters have conspired against the Superior Bubble Gum Company by unreasonably raising prices.

The "explanation" consists of a 63-page treatise on applied magnology by Professor Osbert Garet of Cavalier which the editor (a) does not understand; (b) lacks space to publish; and which (it being atrociously handwritten) he (c) has not the temerity to ask his linotype operator to set.

Don said, "I'm beginning to like this Ed Clark."

"He's a doll," Alis said. "He's about the only one in town who stands up to Father."

"Does your father claim that he levitated Superior off the face of the Earth?"

"Not to me he doesn't. I'm one of those banes of his existence, a skeptic. He gave up trying to magnolize me when I was sixteen. I had a science teacher in high school—not in Superior, incidentally—who gave me all kinds of embarrassing questions to ask Father. I asked them, being a natural-born needler, and Father has disowned me intellectually ever since."

"How old are you, Miss Garet, if I may ask?"

She sat up straight and tucked her sweater tightly into her skirt, emphasizing her good figure. To a male friend Don would have described the figure as outstanding. She had mocking eyes, a pert nose and a mouth of such moist red softness that it seemed perpetually waiting to be kissed. All in all she could have been the queen of a campus much more densely populated with co-eds than Cavalier was.

"You may call me Alis," she said. "And I'm nineteen."

Don grinned. "Going on?"

"Three months past. How old are you, Mr. Cort?"

"Don's the name I've had for twenty-six years. Please use it."

"Gladly. And now, Don, unless you want another cup of coffee, I'll go with you to the end of the world."

"On such short notice?" Don was intrigued. Last night the redhead from the club car had repelled an advance that hadn't been made, and this morning a blonde was apparently making an advance that hadn't been solicited. He wondered where Geneva Jervis was, but only vaguely.

"I'll admit to the double entendre," Alis said. "What I meant—for now—was that we can stroll out to where Superior used to be attached to the rest of Ohio and see how the Earth is getting along without us."

"Delighted. But don't you have any classes?"

"Sure I do. Non-Einsteinian Relativity 1, at nine o'clock. But I'm a demon class-cutter, which is why I'm still a Senior at my advanced age. On to the brink!"

They walked south from the campus and came to the railroad track. The train was standing there with nowhere to go. It had been abandoned except for the conductor, who had dutifully spent the night aboard.

"What's happening?" he asked when he saw them. "Any word from down there?"

"Not that I know of," Don said. He introduced him to Alis Garet. "What are you going to do?"

"What can I do?" the conductor asked.

"You can go over to Cavalier and have breakfast," Alis said. "Nobody's going to steal your old train."

The conductor reckoned as how he might just do that, and did.

"You know," Don said, "I was half-asleep last night but before the train stopped I thought it was running alongside a creek for a while."

"South Creek," Alis said. "That's right. It's just over there."

"Is it still? I mean hasn't it all poured off the edge by now? Was that Superior's water supply?"

Alis shrugged. "All I know is you turn on the faucet and there's water. Let's go look at the creek."

They found it coursing along between the banks.

"Looks just about the same," she said.

"That's funny. Come on; let's follow it to the edge."

The brink, as Alis called it, looked even more awesome by daylight. Everything stopped short. There were the remnants of a cornfield, with the withered stalks cut down, then there was nothing. There was South Creek surging along, then nothing. In the distance a clump of trees, with a few autumn leaves still clinging to their branches, simply ended.

"Where is the water going?" Don asked. "I can't make it out."

"Down, I'd say. Rain for the Earth-people."

"I should think it'd be all dried up by now. I'm going to have a look."

"Don't! You'll fall off!"

"I'll be careful." He walked cautiously toward the edge. Alis followed him, a few feet behind. He stopped a yard from the brink and waited for a spell of dizziness to pass. The Earth was spread out like a topographer's map, far below. Don took another wary step, then sat down.

"Chicken," said Alis. She laughed uncertainly, then she sat down, too.

"I still can't see where the water goes," Don said. He stretched out on his stomach and began to inch forward. "You stay there."

Finally he had inched to a point where, by stretching out a hand, he could almost reach the edge. He gave another wriggle and the fingers of his right hand closed over the brink. For a moment he lay there, panting, head pressed to the ground.

"How do you feel?" Alis asked.

"Scared. When I get my courage back I'll pick up my head and look."

Alis put a hand out tentatively, then purposefully took hold of his ankle and held it tight. "Just in case a high wind comes along," she said.

"Thanks. It helps. Okay, here we go." He lifted his head. "Damn."

"What?"

"It still isn't clear. Do you have a pocket mirror?"

"I have a compact." She took it out of her bag with her

Comments (0)