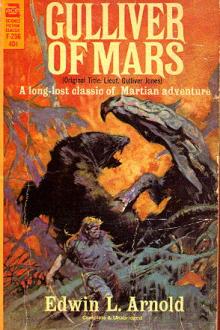

Gulliver of Mars by Edwin Lester Arnold (book recommendations based on other books txt) 📗

- Author: Edwin Lester Arnold

Book online «Gulliver of Mars by Edwin Lester Arnold (book recommendations based on other books txt) 📗». Author Edwin Lester Arnold

"Yes, yes," I said at last, returning to the stove and taking my stand, hands in pockets, in front of it, "anything were better than this, any enterprise however wild, any adventure however desperate. Oh, I wish I were anywhere but here, anywhere out of this redtape-ridden world of ours! I WISH I WERE IN THE PLANET MARS!"

How can I describe what followed those luckless words? Even as I spoke the magic carpet quivered responsively under my feet, and an undulation went all round the fringe as though a sudden wind were shaking it. It humped up in the middle so abruptly that I came down sitting with a shock that numbed me for the moment. It threw me on my back and billowed up round me as though I were in the trough of a stormy sea. Quicker than I can write it lapped a corner over and rolled me in its folds like a chrysalis in a cocoon. I gave a wild yell and made one frantic struggle, but it was too late. With the leathery strength of a giant and the swiftness of an accomplished cigar-roller covering a "core" with leaf, it swamped my efforts, straightened my limbs, rolled me over, lapped me in fold after fold till head and feet and everything were gone—crushed life and breath back into my innermost being, and then, with the last particle of consciousness, I felt myself lifted from the floor, pass once round the room, and finally shoot out, point foremost, into space through the open window, and go up and up and up with a sound of rending atmospheres that seemed to tear like riven silk in one prolonged shriek under my head, and to close up in thunder astern until my reeling senses could stand it no longer, and time and space and circumstances all lost their meaning to me.

CHAPTER II

How long that wild rush lasted I have no means of judging. It may have been an hour, a day, or many days, for I was throughout in a state of suspended animation, but presently my senses began to return and with them a sensation of lessening speed, a grateful relief to a heavy pressure which had held my life crushed in its grasp, without destroying it completely. It was just that sort of sensation though more keen which, drowsy in his bunk, a traveller feels when he is aware, without special perception, harbour is reached and a voyage comes to an end. But in my case the slowing down was for a long time comparative. Yet the sensation served to revive my scattered senses, and just as I was awakening to a lively sense of amazement, an incredible doubt of my own emotions, and an eager desire to know what had happened, my strange conveyance oscillated once or twice, undulated lightly up and down, like a woodpecker flying from tree to tree, and then grounded, bows first, rolled over several times, then steadied again, and, coming at last to rest, the next minute the infernal rug opened, quivering along all its borders in its peculiar way, and humping up in the middle shot me five feet into the air like a cat tossed from a schoolboy's blanket.

As I turned over I had a dim vision of a clear light like the shine of dawn, and solid ground sloping away below me. Upon that slope was ranged a crowd of squatting people, and a staid-looking individual with his back turned stood nearer by. Afterwards I found he was lecturing all those sitters on the ethics of gravity and the inherent properties of falling bodies; at the moment I only knew he was directly in my line as I descended, and him round the waist I seized, giddy with the light and fresh air, waltzed him down the slope with the force of my impetus, and, tripping at the bottom, rolled over and over recklessly with him sheer into the arms of the gaping crowd below. Over and over we went into the thickest mass of bodies, making a way through the people, until at last we came to a stop in a perfect mound of writhing forms and waving legs and arms. When we had done the mass disentangled itself and I was able to raise my head from the shoulder of someone on whom I had fallen, lifting him, or her—which was it?—into a sitting posture alongside of me at the same time, while the others rose about us like wheat-stalks after a storm, and edged shyly off, as well as they might.

Such a sleek, slim youth it was who sat up facing me, with a flush of gentle surprise on his face, and dapper hands that felt cautiously about his anatomy for injured places. He looked so quaintly rueful yet withal so good-tempered that I could not help bursting into laughter in spite of my own amazement. Then he laughed too, a sedate, musical chuckle, and said something incomprehensible, pointing at the same time to a cut upon my finger that was bleeding a little. I shook my head, meaning thereby that it was nothing, but the stranger with graceful solicitude took my hand, and, after examining the hurt, deliberately tore a strip of cloth from a bright yellow toga-like garment he was wearing and bound the place up with a woman's tenderness.

Meanwhile, as he ministered, there was time to look about me. Where was I? It was not the Broadway; it was not Staten Island on a Saturday afternoon. The night was just over, and the sun on the point of rising. Yet it was still shadowy all about, the air being marvellously tepid and pleasant to the senses. Quaint, soft aromas like the breath of a new world—the fragrance of unknown flowers, and the dewy scent of never-trodden fields drifted to my nostrils; and to my ears came a sound of laughter scarcely more human than the murmur of the wind in the trees, and a pretty undulating whisper as though a great concourse of people were talking softly in their sleep. I gazed about scarcely knowing how much of my senses or surroundings were real and how much fanciful, until I presently became aware the rosy twilight was broadening into day, and under the increasing shine a strange scene was fashioning itself.

At first it was an opal sea I looked on of mist, shot along its upper surface with the rosy gold and pinks of dawn. Then, as that soft, translucent lake ebbed, jutting hills came through it, black and crimson, and as they seemed to mount into the air other lower hills showed through the veil with rounded forest knobs till at last the brightening day dispelled the mist, and as the rosy-coloured gauzy fragments went slowly floating away a wonderfully fair country lay at my feet, with a broad sea glimmering in many arms and bays in the distance beyond. It was all dim and unreal at first, the mountains shadowy, the ocean unreal, the flowery fields between it and me vacant and shadowy.

Yet were they vacant? As my eyes cleared and day brightened still more, and I turned my head this way and that, it presently dawned upon me all the meadow coppices and terraces northwards of where I lay, all that blue and spacious ground I had thought to be bare and vacant, were alive with a teeming city of booths and tents; now I came to look more closely there was a whole town upon the slope, built as might be in a night of boughs and branches still unwithered, the streets and ways of that city in the shadows thronged with expectant people moving in groups and shifting to and fro in lively streams—chatting at the stalls and clustering round the tent doors in soft, gauzy, parti-coloured crowds in a way both fascinating and perplexing.

I stared about me like a child at its first pantomime, dimly understanding all I saw was novel, but more allured to the colour and life of the picture than concerned with its exact meaning; and while I stared and turned my finger was bandaged, and my new friend had been lisping away to me without getting anything in turn but a shake of the head. This made him thoughtful, and thereon followed a curious incident which I cannot explain. I doubt even whether you will believe it; but what am I to do in that case? You have already accepted the episode of my coming, or you would have shut the covers before arriving at this page of my modest narrative, and this emboldens me. I may strengthen my claim on your credulity by pointing out the extraordinary marvels which science is teaching you even on our own little world. To quote a single instance: If any one had declared ten years ago that it would shortly be practicable and easy for two persons to converse from shore to shore across the Atlantic without any intervening medium, he would have been laughed at as a possibly amusing but certainly extravagant romancer. Yet that picturesque lie of yesterday is amongst the accomplished facts of today! Therefore I am encouraged to ask your indulgence, in the name of your previous errors, for the following and any other instances in which I may appear to trifle with strict veracity. There is no such thing as the impossible in our universe!

When my friendly companion found I could not understand him, he looked serious for a minute or two, then shortened his brilliant yellow toga, as though he had arrived at some resolve, and knelt down directly in front of me. He next took my face between his hands, and putting his nose within an inch of mine, stared into my eyes with all his might. At first I was inclined to laugh, but before long the most curious sensations took hold of me. They commenced with a thrill which passed all up my body, and next all feeling save the consciousness of the loud beating of my heart ceased. Then it seemed that boy's eyes were inside my head and not outside, while along with them an intangible something pervaded my brain. The sensation at first was like the application of ether to the skin—a cool, numbing emotion. It was followed by a curious tingling feeling, as some dormant cells in my mind answered to the thought-transfer, and were filled and fertilised! My other brain-cells most distinctly felt the vitalising of their companions, and for about a minute I experienced extreme nausea and a headache such as comes from over-study, though both passed swiftly off. I presume that in the future we shall all obtain knowledge in this way. The Professors of a later day will perhaps keep shops for the sale of miscellaneous information, and we shall drop in and be inflated with learning just as the bicyclist gets his tire pumped up, or the motorist is recharged with electricity at so much per unit. Examinations will then become matters of capacity in the real meaning of that word, and we shall be tempted to invest our pocket-money by advertisements of "A cheap line in Astrology," "Try our double-strength, two-minute course of Classics," "This is remnant day for Trigonometry and Metaphysics," and so on.

My friend did not get as far as that. With him the process did not take more than a minute, but it was startling in its results, and reduced me to an extraordinary state of hypnotic receptibility. When it was over my instructor tapped with a finger on my lips, uttering aloud as he did so the words—

"Know none; know some; know little; know morel" again and again; and the strangest part of it is that as he spoke I did know at first a little, then more, and still more, by swift accumulation, of his speech and meaning. In fact, when presently he suddenly laid a hand over my eyes and then let go of my head with a pleasantly put question as to how I felt, I had no difficulty whatever in answering him in his own tongue, and rose from the ground as one gets from a hair-dresser's chair, with a vague idea of looking round for my hat and offering him his fee.

"My word, sir!" I said, in lisping Martian, as I pulled down my cuffs and put my cravat straight,

Comments (0)