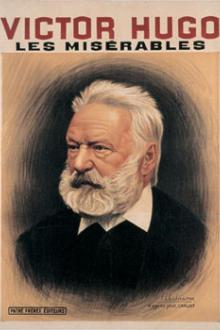

Les Misérables - Victor Hugo (best finance books of all time TXT) 📗

- Author: Victor Hugo

- Performer: 0451525264

Book online «Les Misérables - Victor Hugo (best finance books of all time TXT) 📗». Author Victor Hugo

Hence the advent, apparently tardy, of the Tacituses and the Juvenals; it is in the hour for evidence, that the demonstrator makes his appearance.

But Juvenal and Tacitus, like Isaiah in Biblical times, like Dante in the Middle Ages, is man; riot and insurrection are the multitude, which is sometimes right and sometimes wrong.

In the majority of cases, riot proceeds from a material fact; insurrection is always a moral phenomenon. Riot is Masaniello; insurrection, Spartacus. Insurrection borders on mind, riot on the stomach; Gaster grows irritated; but Gaster, assuredly, is not always in the wrong. In questions of famine, riot, Buzançais, for example, holds a true, pathetic, and just point of departure. Nevertheless, it remains a riot. Why? It is because, right at bottom, it was wrong in form. Shy although in the right, violent although strong, it struck at random; it walked like a blind elephant; it left behind it the corpses of old men, of women, and of children; it wished the blood of inoffensive and innocent persons without knowing why. The nourishment of the people is a good object; to massacre them is a bad means.

All armed protests, even the most legitimate, even that of the 10th of August, even that of July 14th, begin with the same troubles. Before the right gets set free, there is foam and tumult. In the beginning, the insurrection is a riot, just as a river is a torrent. Ordinarily it ends in that ocean: revolution. Sometimes, however, coming from those lofty mountains which dominate the moral horizon, justice, wisdom, reason, right, formed of the pure snow of the ideal, after a long fall from rock to rock, after having reflected the sky in its transparency and increased by a hundred affluents in the majestic mien of triumph, insurrection is suddenly lost in some quagmire, as the Rhine is in a swamp.

All this is of the past, the future is another thing. Universal suffrage has this admirable property, that it dissolves riot in its inception, and, by giving the vote to insurrection, it deprives it of its arms. The disappearance of wars, of street wars as well as of wars on the frontiers, such is the inevitable progression. Whatever To-day may be, To-morrow will be peace.

However, insurrection, riot, and points of difference between the former and the latter,—the bourgeois, properly speaking, knows nothing of such shades. In his mind, all is sedition, rebellion pure and simple, the revolt of the dog against his master, an attempt to bite whom must be punished by the chain and the kennel, barking, snapping, until such day as the head of the dog, suddenly enlarged, is outlined vaguely in the gloom face to face with the lion.

Then the bourgeois shouts: “Long live the people!”

This explanation given, what does the movement of June, 1832, signify, so far as history is concerned? Is it a revolt? Is it an insurrection?

It may happen to us, in placing this formidable event on the stage, to say revolt now and then, but merely to distinguish superficial facts, and always preserving the distinction between revolt, the form, and insurrection, the foundation.

This movement of 1832 had, in its rapid outbreak and in its melancholy extinction, so much grandeur, that even those who see in it only an uprising, never refer to it otherwise than with respect. For them, it is like a relic of 1830. Excited imaginations, say they, are not to be calmed in a day. A revolution cannot be cut off short. It must needs undergo some undulations before it returns to a state of rest, like a mountain sinking into the plain. There are no Alps without their Jura, nor Pyrenees without the Asturias.

This pathetic crisis of contemporary history which the memory of Parisians calls “the epoch of the riots,” is certainly a characteristic hour amid the stormy hours of this century. A last word, before we enter on the recital.

The facts which we are about to relate belong to that dramatic and living reality, which the historian sometimes neglects for lack of time and space. There, nevertheless, we insist upon it, is life, palpitation, human tremor. Petty details, as we think we have already said, are, so to speak, the foliage of great events, and are lost in the distance of history. The epoch, surnamed “of the riots,” abounds in details of this nature. Judicial inquiries have not revealed, and perhaps have not sounded the depths, for another reason than history. We shall therefore bring to light, among the known and published peculiarities, things which have not heretofore been known, about facts over which have passed the forgetfulness of some, and the death of others. The majority of the actors in these gigantic scenes have disappeared; beginning with the very next day they held their peace; but of what we shall relate, we shall be able to say: “We have seen this.” We alter a few names, for history relates and does not inform against, but the deed which we shall paint will be genuine. In accordance with the conditions of the book which we are now writing, we shall show only one side and one episode, and certainly, the least known at that, of the two days, the 5th and the 6th of June, 1832, but we shall do it in such wise that the reader may catch a glimpse, beneath the gloomy veil which we are about to lift, of the real form of this frightful public adventure.

CHAPTER III—A BURIAL; AN OCCASION TO BE BORN AGAIN

In the spring of 1832, although the cholera had been chilling all minds for the last three months and had cast over their agitation an indescribable and gloomy pacification, Paris had already long been ripe for commotion. As we have said, the great city resembles a piece of artillery; when it is loaded, it suffices for a spark to fall, and the shot is discharged. In June, 1832, the spark was the death of General Lamarque.

Lamarque was a man of renown and of action. He had had in succession, under the Empire and under the Restoration, the sorts of bravery requisite for the two epochs, the bravery of the battle-field and the bravery of the tribune. He was as eloquent as he had been valiant; a sword was discernible in his speech. Like Foy, his predecessor, after upholding the command, he upheld liberty; he sat between the left and the extreme left, beloved of the people because he accepted the chances of the future, beloved of the populace because he had served the Emperor well; he was, in company with Comtes Gérard and Drouet, one of Napoleon’s marshals in petto. The treaties of 1815 removed him as a personal offence. He hated Wellington with a downright hatred which pleased the multitude; and, for seventeen years, he majestically preserved the sadness of Waterloo, paying hardly any attention to intervening events. In his death agony, at his last hour, he clasped to his breast a sword which had been presented to him by the officers of the Hundred Days. Napoleon had died uttering the word army, Lamarque uttering the word country.

His death, which was expected, was dreaded by the people as a loss, and by the government as an occasion. This death was an affliction. Like everything that is bitter, affliction may turn to revolt. This is what took place.

On the preceding evening, and on the morning of the 5th of June, the day appointed for Lamarque’s burial, the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which the procession was to touch at, assumed a formidable aspect. This tumultuous network of streets was filled with rumors. They armed themselves as best they might. Joiners carried off door-weights of their establishment “to break down doors.” One of them had made himself a dagger of a stocking-weaver’s hook by breaking off the hook and sharpening the stump. Another, who was in a fever “to attack,” slept wholly dressed for three days. A carpenter named Lombier met a comrade, who asked him: “Whither are you going?” “Eh! well, I have no weapons.” “What then?” “I’m going to my timber-yard to get my compasses.” “What for?” “I don’t know,” said Lombier. A certain Jacqueline, an expeditious man, accosted some passing artisans: “Come here, you!” He treated them to ten sous’ worth of wine and said: “Have you work?” “No.” “Go to Filspierre, between the Barrière Charonne and the Barrière Montreuil, and you will find work.” At Filspierre’s they found cartridges and arms. Certain well-known leaders were going the rounds, that is to say, running from one house to another, to collect their men. At Barthélemy’s, near the Barrière du Trône, at Capel’s, near the Petit-Chapeau, the drinkers accosted each other with a grave air. They were heard to say: “Have you your pistol?” “Under my blouse.” “And you?” “Under my shirt.” In the Rue Traversière, in front of the Bland workshop, and in the yard of the Maison-Brulée, in front of tool-maker Bernier’s, groups whispered together. Among them was observed a certain Mavot, who never remained more than a week in one shop, as the masters always discharged him “because they were obliged to dispute with him every day.” Mavot was killed on the following day at the barricade of the Rue Ménilmontant. Pretot, who was destined to perish also in the struggle, seconded Mavot, and to the question: “What is your object?” he replied: “Insurrection.” Workmen assembled at the corner of the Rue de Bercy, waited for a certain Lemarin, the revolutionary agent for the Faubourg Saint-Marceau. Watchwords were exchanged almost publicly.

On the 5th of June, accordingly, a day of mingled rain and sun, General Lamarque’s funeral procession traversed Paris with official military pomp, somewhat augmented through precaution. Two battalions, with draped drums and reversed arms, ten thousand National Guards, with their swords at their sides, escorted the coffin. The hearse was drawn by young men. The officers of the Invalides came immediately behind it, bearing laurel branches. Then came an innumerable, strange, agitated multitude, the sectionaries of the Friends of the People, the Law School, the Medical School, refugees of all nationalities, and Spanish, Italian, German, and Polish flags, tricolored horizontal banners, every possible sort of banner, children waving green boughs, stone-cutters and carpenters who were on strike at the moment, printers who were recognizable by their paper caps, marching two by two, three by three, uttering cries, nearly all of them brandishing sticks, some brandishing sabres, without order and yet with a single soul, now a tumultuous rout, again a column. Squads chose themselves leaders; a man armed with a pair of pistols in full view, seemed to pass the host in review, and the files separated before him. On the side alleys of the boulevards, in the branches of the trees, on balconies, in windows, on the roofs, swarmed the heads of men, women, and children; all eyes were filled with anxiety. An armed throng was passing, and a terrified throng looked on.

The Government, on its side, was taking observations. It observed with its hand on its sword. Four squadrons of carabineers could be seen in the Place Louis XV. in their saddles, with their trumpets at their head, cartridge-boxes filled and muskets loaded, all in readiness to march; in the Latin country and at the Jardin des Plantes, the Municipal Guard echelonned from street to street; at the Halle-aux-Vins, a

Comments (0)