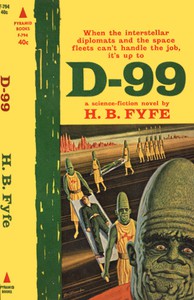

D-99: a science-fiction novel by H. B. Fyfe (cool books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: H. B. Fyfe

Book online «D-99: a science-fiction novel by H. B. Fyfe (cool books to read TXT) 📗». Author H. B. Fyfe

"Never mind, Willie," Simonetta said. "I didn't mean I was collapsing. Come on, Beryl, let's see if there's any coffee or tea left."

"Wait for me," said Pauline. "I've got to take this phone off the outside line anyway."

Smith stepped forward to plant one hand behind Lydman's shoulder blade.

"I could use a martini, myself," he called after the girls. "How about the rest of you? Pete? Willie?"

Parrish seconded the motion, Westervelt said he would be right along, and trailed them slowly to the door. He paused to look back, and he and Joe exchanged brow-mopping gestures.

The rest of them were trouping along the corridor without much talk. He ambled along until the men, bringing up the rear, had turned the corner. Then he ducked into the library.

He fingered his eye again. Either it was a trifle less sore or he was getting used to it. He still hesitated to face an office full of people and good lighting.

"There must be something around here to read," he muttered.

He walked over to a stack of current magazines. Most of them were technical in nature; but several dealt with world and galactic news. He took a few to a seat at the long table and began to leaf through one.

It must have been about fifteen minutes later that Simonetta showed up, bearing a sealed cup of tea and one of coffee.

"So that's where you are!" she said. "I was taking something to Joe, and thought maybe I'd find you along the way."

Westervelt deduced that she had phoned the operator.

"You can have the coffee," she said, setting it beside his magazine. "Joe said he'd rather have tea this time around."

Westervelt looked up. Simonetta saw his eye and pursed her lips.

"Well!"

"How does it look?" asked Westervelt glumly.

"Kind of pretty. If I remember the ones my brothers used to bring home, it will be ravishingly beautiful by tomorrow!"

"That's what I was afraid of," said Westervelt.

Simonetta laughed. She set the tea aside and pulled out a chair.

"I don't think it's really that bad, Willie," she told him. "I was only fooling."

"It shows though, huh?"

"Oh ... yes ... it shows."

"That's what I like about you, Si," said Westervelt. "You don't ask nasty, embarrassing questions like how it happened or which door closed on me."

Following which he told her nearly the whole story, leaving out only the true origin of the quarrel. He suspected that Simonetta could put two and two together, but he meant to tell nobody about the start of it.

"Ah, Willie," she said with a grin at the conclusion, "if you had to fall for a blonde, why couldn't you pick little Pauline?"

"I guess you're right."

"Now, don't take that so seriously too! Beryl's a good sort, on the whole. In a day or two, this will all blow over. Come on with me to see Joe, then we'll go back and say you got something in your eye."

"But when?"

"Oh ... during the message from Yoleen. You didn't want to bother anybody at the time, so you foolishly kept rubbing until it got sore."

"That's all right," said Westervelt, "but Beryl knows different."

"If she opens her mouth, I shall personally punch her in the eye!" declared Simonetta.

She giggled at the idea, and he found himself grinning.

They went along the corridor to deliver the tea to Rosenkrantz, and then returned to the main office. An air of complete informality prevailed, a reaction from the scene they had witnessed. There was a good deal of wandering about with drinks, sitting on desks, and inconsequential chatter.

No one seemed to want to talk shop, and Westervelt guessed that Smith was just as pleased to be able to kill some time. He himself quietly slipped around the corner to his own desk, where he propped his heels up and sipped his coffee.

Westervelt listened as Parrish and Smith told a few jokes. The stories tended to be more ironic than funny, and no one was expected to laugh out loud.

Pauline, from her switchboard, buzzed the phone on Simonetta's desk, since most of those present had gravitated to that end of the office. Smith looked around in the middle of an account of his struggles with his radio-controlled lawn mower.

"Want to take that, Willie?" he said, with a bare suggestion of a wink.

Westervelt lifted a hand in assent. He climbed out of his chair and went to the phone on Beryl's desk, where he would be as nearly private as possible.

"Who is it, Pauline?" he asked when she came on.

"It's Joe. He wants to talk to Mr. Smith."

"Give it here on number seven," said Westervelt. "The boss is talking."

Pauline blanked out and was replaced by the communications man. Rosenkrantz showed a flicker of surprise at the sight of Westervelt.

"Smitty's in a crowd," murmured the youth. "Something up?"

"Not much, maybe," said the other. "A message came in by commercial TV. I guess they didn't think it was too urgent, but I'll give you the facts if you think Smitty would like to know."

"Hold on," said Westervelt. "Let's see ... where does Beryl keep a pen?"

He dug out a scratch pad and something to scribble with, and nodded.

"One of our own agents," said Joe, "named Robertson, signed this. You've seen his reports, I guess."

"Yeah, sounds familiar."

"It says, after reading between our standard code expressions, that two spacers and a tourist were convicted of inciting revolution on Epsilon Indi II. They gave the names, and all, which I taped."

"That's practically in our back yard," said Westervelt. "Maybe he just wants to alert us, but the D.I.R. ought to be working on that publicly. Sure there wasn't any hint it was urgent?"

"No, and like I said, it came by commercial relay."

"Okay. The boss has enough on his mind at the moment. Let's figure on having a tape for him to look at in the morning. I'll find a chance to mention it to him, so he'll know about it. All right?"

"All right with me," grinned Rosenkrantz. "If anything goes wrong, I'll refer them to you. Be prepared to have your other eye spit in."

He cut off, leaving Westervelt with his mouth open and his regained aplomb shaky. The youth waited until he caught Smith's eye, and shook his head to indicate the unimportance of the call. He wondered if he ought to take time to phone downstairs for a report on the situation. It did not strike him as worth the risk with all the people in the same room.

He saw Beryl strolling his way and rose from her chair.

"That's all right, Willie," she said calmly, setting her packaged drink on the desk. "I just wanted to give you back your handkerchief."

She produced it from the purse lying on her desk and said, "Thanks again. I'm sorry about the make-up marks."

"Forget it," said Westervelt.

"I'm sorry about the eye too," said Beryl, raising her eyes for the first time to examine the damage. "It ... doesn't look as bad as Si said."

"Well, that's a comfort, anyway. I got something in it and rubbed too hard, you know."

"Yes, she told me," said Beryl. "To tell the truth, Willie, I didn't know I could do it."

"Aw, it was a lucky swing," muttered Westervelt.

"Yes ... I, well ... you might say I was a little upset."

"I'm sorry I started it all," said Westervelt. "How about letting me buy you a lunch to make up."

Beryl shrugged, looking serious.

"I don't mind, if we make it Dutch. It was as much my fault. I hope we're both around to go to lunch tomorrow. It gives me the creeps."

"What does?" asked Westervelt.

"The way Mr. Lydman looks. Something about his eyes...."

Westervelt turned his head to stare across the room, wondering if the worst had occurred.

SEVENTEENJohn Willard set a brisk pace through the streets of First Haven, as befitted a conscientious public servant. Maria Ringstad kept up with him as best she could. When she lagged, the thin cord tightened around her wrist, and he grumbled over his shoulder at her. Naturally, she carried her bag.

He had explained that they would have been most inconspicuous with her walking properly a yard behind him. Anyone would then have taken them for man and wife or man and servant—had it not been for her Terran clothing.

"To walk the street with you in that rig would attract entirely too much attention," was his explanation. "The only thing we can do is use the public symbol of restraint, so that everyone will know you are a prisoner."

"What good will that do? Won't they still stare."

"It is considered improper, as well as imprudent. No law-abiding citizen would wish to risk being suspected of a sympathetic curiosity about a transgressor."

"You make it sound dangerous," said Maria, holding out her hand obediently.

Anything to be inconspicuous, she had thought.

Now, turning a corner about three hundred yards from the jail, she had to admit that the system seemed to be working. The Greenies whom they met were nearly all interested in other things: a shop in the vicinity, another Greenie across the street, a paving stone over which they had just tripped, or the condition of the wall above Maria's head.

Willard led her to the far side of a broader avenue after they had negotiated the corner that put them permanently out of sight of the jail. Maria tried to recall the scanty information he had whispered to her against the outside wall of the prison.

There had been time for him to tell her he was sent by the Department of Interstellar Relations of Terra to get her out, since it had proved impossible to alter the attitude of the Greenie legal authorities. Maria was not quite sure whether he was really the prison officer he said he was, in which case he must have been bribed on a scale to make her own "crime" ridiculous, or whether he was an independent worker friendly to the Terran space line, in which case the payment might more charitably be regarded as a fee.

She knew that he planned to deliver her to a spaceship due to leave shortly. There had been no opportunity for her to ask the destination.

To tell the truth, she reflected, I don't care where it is. Anything would be a haven from Greenhaven!

She began to amuse herself by planning the article she would write when back on Terra. "How I escaped from Paradise" might do it. Or "Prison-breaking in Paradise." Or perhaps "Greenhaven or Green Hell."

Whatever I call it, she promised herself, I'll skin them alive. And I'll find a way to send the judge and the warden copies of it, too!

Maybe, she pondered, it might even be better to stretch it out to a whole book and get someone to do a series of unflattering cartoons of Greenie characters.

The cord jerked at her wrist. She realized that she had fallen behind again, and made an apologetic face at Willard when he looked back.

"Don't do that!" he hissed. "They'll wonder why I tolerate disrespect."

"Sorry!" said Maria, shrugging unrepentantly. "You take this pretty seriously, don't you."

"You'd better take it seriously yourself," he growled. "It's your neck as much as mine!"

He glared at a young Greenie who had glanced curiously from the opposite side of the avenue. The abashed citizen hastily averted his eyes. Willard gave the cord a significant twitch and strode on.

They turned another corner, to the right this time, and went along a narrow side street for about two hundred yards. Waiting for a moment when he might meet as few people as possible, Willard crossed to the other side. A little further on, he led the way into what could almost be termed an alley.

Willard stopped.

"Now, we are going into this small food shop," he informed Maria. "You would call it a cafe or restaurant on Terra. It will seem normal enough for an officer to provide his charge with food for a journey, so that will be reasonable."

"Is the food any better than what I've been getting?" asked Maria.

"It doesn't matter. We won't stop there, since it would be impolite to inflict the sight of you upon honest citizens at their meal. I shall request a private room, and the keeper will lead us to the rear."

"Humph! Well if that's the way it is, then that's the way it is. So in the eyes of an honest Greenie I'm something to spoil his appetite. What can I do about that?"

"What you can do is keep that big, flexible, active mouth of yours shut!" declared Willard. "Otherwise, I shall simply drop the end of the cord and take off. You can find your own way out."

"I'm sorry," apologized Maria, a shade too meekly. "I promise I'll be oh-so-good. Do you

Comments (0)