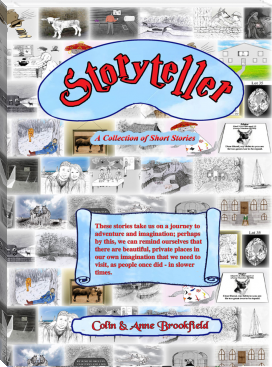

Storyteller - Colin & Anne Brookfield (ebook and pdf reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Colin & Anne Brookfield

Book online «Storyteller - Colin & Anne Brookfield (ebook and pdf reader .txt) 📗». Author Colin & Anne Brookfield

It wasn’t until the locomotive finally ran out of fuel that he decided there were other things to be done, and disappeared out of the door.

“I noticed that Mr. Persill is very quiet,” Peter observed, “I do hope my presence isn’t offending him.”

“Not at all,” she said, “father never could string more than three or four words together at one time. ‘Is father was just the same. Anyway, who is there to talk to out there in the fields all day ‘cept the ‘orse and, ‘ees got even less to say.”

He took the opportunity to change the subject. “What happened to William? Why didn’t he have dinner with us?”

“Oh, he wasn’t feeling too good, so I gave him a little to eat and put him to bed. ‘Ee’ll be right enough upon the morrow. Now, you’ll be feeling rather tired I expect. Perhaps I should show you to your room. I start cooking breakfast at six every morning, but you get up when it suits you. One little thing I should mention though, if you go out passed the cowshed in the morning, pr’aps you could make sure to close the wicket behind you or we might ‘ave the animals at the vegetables.”

“Certainly, and six in the morning will do me fine. I’m not sure whether I mentioned it before, but I expect to be back rather late each day, if that’s alright with you.”

Having nodded her approval, Mrs. Persill reached up to the mantle shelf to bring down a candle holder. “Follow me,” she said, “and I’ll show you to your room.” The candle wick was lit and she proceeded through the curtained opening and up the steep stairs. The stair handrail turned out to be rather a surprise; it was just a tree branch, about two inches in diameter, still with its original bark on it, which he found rather amusing. At the top of the stairs, they came to a small landing with three rooms leading off it.

“Ere we are,” she said opening the first door. The room was quite a good size, or it would have been had it not been for the large double-size iron-framed bedstead that in turn, was almost swamped by its high mattress and overlapping quilt.

Peter looked out of the window while she checked that all was well. In the dim light he could make out the form of Mr. Persill, digging a long trench across the vegetable garden.

“Doesn’t your husband ever stop work?” he asked.

“Ee ‘as to keep busy sir, we ‘ave to get all our vegetables in whilst the weather is suitable, because come winter, if we’ve not enough to get us through, then we go ‘ungry. You see we only rent this farm; what we grow in the lower field must pay the rent and feed the animals. Then there are things like oil for the lamps, candles and peat for the range. It don’t leave much to spare even in a good year.”

Next, Mrs. Persill pointed to where her husband was working.

“Now that long trench that father’s digging, is for next year’s prize carrots and parsnips. It’ll be almost as deep as I am by the time ‘ee ‘as finished. Then he fetches our ‘orse and cart to the spinney for leaf mould, and that’s laid through the bottom of the trench. Then father sieves all of the soil back in the trench. That way, his prize parsnips and carrots grow downwards nice and straight, ‘cos there’s no stones in their way.”

Peter was amused by her animations and chatter.

“Ee always gets first prize at shows. They call father ‘The Carrot and Parsnip King of Salop’. The worst part of the whole business for me, is when it’s time to dig ‘em up. You see it’s my job to sit on the ground and hang on to the vegetable, whilst father burrows down like a rabbit ‘till he comes to the very last whiskery point. It all counts when it’s measured by the judges, but believe me, father is very touchy at these times because, if I move one little bit, it might ruin the vegetable. But you want to see them when they’re all cleaned up! Most of them are taller than William when they’re stood on end.”

“It sounds very interesting,” Peter replied.

“Now, you see those tiny little hillock-like heaps in a row across the bottom end of the vegetable patch? Well, that’s what we call ‘clamps’. They’re full of potatoes that have been layered in, and covered with straw with a thick layer of earth over the top, so as the frost can’t get to ‘em in the winter. What I do, is open up the side of one of ‘em when I need potatoes, then I take what I want and block the hole up till the next time.”

“What a great idea,” he replied

“Rabbits are a problem, so we let our dog Gyp off the chain at night so as he can patrol the vegetables, otherwise the varmints gobble them up. Father is usually out at first light to get us a few rabbits, but ‘ee’s run clear out of black powder.”

“Black powder? What on earth is that?” Peter enquired.

“Well, I can see you don’t know much about guns in the city. Black powder is what you pour down the muzzle, then you put some wadding in, followed by the lead shot, then more wadding is pushed in to stop the lead pellets falling out of the end of the barrel while you’re hunting the rabbit. When the trigger is squeezed, the hammer hits a little thing that father calls a ‘percussion cap’, and this ignites the black powder. I know it’s a rather old sort of gun, but some of the farmers round ‘ere still ‘ave ‘em. They often borrow black powder off one another till they get more in from the village shop.”

“Do you know, I never realised what went on in the countryside, I’ve never thought about it before,” murmured Peter thoughtfully. He could see that Mrs. Persill was pleased with that remark.

“I’d better be getting on,” she said, “there’s lots to do before father and I retire. There’s a snuff on the side of the candle holder when you want to put the candle out and there’s a pot under the bed, just in case it’s needed,” she said, disappearing through the doorway. “I ‘ope’ you sleep well.”

He would have roared with laughter if it were not for the thought of being overheard. Nobody in their right mind would ever believe that such a left behind place could actually exist at the closing of the second millennium, but he didn’t care what others thought; he found it very special.

Looking under the bed, he discovered a round china object with a handle on one side staring back at him. “Thank you, but no thanks,” he said quietly to himself as he pocketed a small torch, and headed for the stairs.

Mrs. Persill was not to be seen in the main room, so he made his way towards the rear exit. As he passed through the little room where the food was prepared, he saw a large pie dish sitting there full of savoury cooked rabbit. In the centre of the dish, a small china object like an upturned egg cup stood high above the gravy level. Nearby, on a large wooden table, he saw the pastry which had been nicely rolled out ready to cover the pie and realised, that the thing in the pie dish must be to stop the pastry from sagging into the gravy.

Once out into the back yard, he made his way (not without some trepidation) towards that formidable little building at the end of the path. He didn’t get far before Gyp introduced himself with a curl of the upper lip, displaying a set of teeth which a sabre tooth tiger, would have been justly proud.

“Be’ave yourself you varmint,” came the gruff voice of Mr. Persill from somewhere in the bellows of the earth. “Don’t worry sir, ‘ee baint a vicious dog, ‘ee don’t bite strangers.” Peter had an unpleasant feeling that he was very likely to be the first stranger to test the theory.

He encountered Mrs. Persill next, as she made her way towards the house, taking very small steps to avoid disturbing the two pails of water that were hanging either side of her on short ropes from the hand-carved wooden yolk, that lay across her shoulders.

“I’m just getting the water in from the garden pump for the ‘ouse. The ‘orse and cow needs water next, but the pigs ‘ave ‘ad theirs. So I won’t be long now,” she said with a cheery smile.

Peter shone his torch into the little room; there was a shelf and a candle on it ready for lighting. The ‘seat’ was a plank of wood with a hole in it, and a bucket set beneath. On the wall close to hand, was a nail on which some squares of paper, had been unceremoniously spiked.

Getting into bed that evening was an experience like no other. Having first pulled back the heavy quilt, he found it necessary to launch himself upwards and over, so as to negotiate the extreme height of the bed, only to disappear into a crater, as the feather mattress enveloped him.

The next thing he heard was the farmyard alarm clock, telling the world it was time to rise and shine, or perhaps, it was just the cockerel’s way of telling everyone he wanted his breakfast.

It needed the expertise of a seasoned speleologist to get out of the feather mattress; nevertheless, he was soon up and using his battery shaver. A stripped wash in cold water was a new experience, especially when he discovered there had been hot water waiting for him in a jug just outside the bedroom door when he finally opened it.

The mouth-watering smell of eggs and bacon greeted him as he entered the main room. ‘Good mornings’ were said all round, and little William immediately took sanctuary behind his mother’s skirt.

“Ee’s a rum lad is our William; ee’s not used to strangers,” she said, placing a large plate of bacon and eggs in front of Peter. “There’s plenty more bread and butter if you need it,” she said as she poured the tea.

Peter was most intrigued by the tea-pouring process and the unusual teapot; it was rather large by normal standards, made of some sort of pewter-like metal. To pour the tea, the cup and saucer were placed under the bent-over spout and then the teapot lid was lifted by a knob in its centre. But unlike most teapot lids, this one was like pulling the piston out of a car engine, but easier of course. Then the lid was pushed gently downwards whilst a finger sealed the vent hole. This put the contents of the pot under pressure, and lo and behold, out poured the tea from the spout without lifting the pot.

“I’ve put your lunch by the back door with your fishing tackle, and filled that jug-type thing (referring to the thermos flask) you left me, with hot tea. I’m sure it’ll get cold within the hour; I don’t ‘old with these new fangled ideas.

Would you like father to go along and show you some of the special fishing places that he takes William to?”

“No it’s alright,” Peter replied, “I’ve been given a map of places to fish. But thank you anyway.”

William was still well-concealed behind his mother’s skirt, but his eyes kept peeping out to take in every detail of the strange new addition to the family.

“By the way,” Peter enquired, “it has just crossed my mind. How did Barney get her name?”

“Well, our family has farmed ‘ere for about two hundred years or so, with quite a lot of cattle and there was always a ‘Barney’ in amongst the ‘erd, so it became a tradition you might say, and even though

Comments (0)