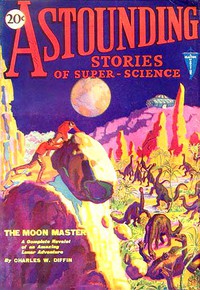

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (best books to read ever .txt) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (best books to read ever .txt) 📗». Author Various

"

But Lindquist's figures prove that the vessel or fleet of the enemy must be of tremendous size to produce such discrepancies, infinitesimally small though they might seem. We have a big fellow with whom to deal, but we know where to find him now."

"How can he work from a fixed position to make his attacks on the earth at such widely separated points?" I asked.

"It isn't a fixed position in the first place, and besides the earth rotates once in twenty-four hours, while the moon travels around the earth once in about twenty-eight days. But, even so, the widespread destruction could not be accounted for. He must send out scouting parties or something of that sort. That is one of the things we are to learn when we get out there. We'll have some fun, Jack."

"Will the Pioneer be ready?" I asked. Evidently I was to go.

"She will, with the exception of the acceleration neutralizers. But I'm having some heavily-cushioned and elastic supports made that will, I believe, save us from injury. And I guess we can stand the discomfort for once."

"Yes," I agreed, "in such a cause, I, for one, am willing to go through anything to help keep this overwhelming disaster from our good old world."

"Jack," he whispered, "we must prevent it. We've got to!"

Then he was gone, and I watched him for a moment as he dashed headlong from one task to another. He was a whirlwind of energy once more.

Forty-three hours and twenty minutes had passed since the receipt of the enemy's ultimatum. The last bolt was being tightened in the remodeled Pioneer, and Secretary Simler and his staff were on hand to witness the take-off of the vessel on which the hopes of the world were pinned. The news of our attempt had been spread by cable and printed news only, for there was fear that the enemy might be able to pick up the broadcasts of the news service and thus be able to anticipate us. As usual, there were many scoffers, but the consensus of opinion was in favor of the project. At any rate, what better expedient was there to offer?

The huge airport, now unused on account of the complete cessation of air traffic, was closed to the public. But there was quite a crowd to witness the take-off, the visitors from Washington, the officials of the field, and the two hundred workers who had enabled us to make ready for the adventure in time. There were four to enter the Pioneer: Hart, George, Professor Lindquist, and myself. And when the entrance manhole was bolted home behind us, the watchers stood in silence, waiting for the roar of the Pioneer's motor. As the starter took hold, Hart waved his hand at one of the ports and every man of those two hundred and some watchers stood at attention and saluted is if he were a born soldier and Hart a born commander-in-chief.

We taxied heavily across the field, for the Pioneer was much overloaded for a quick take-off. She[Pg 76] bumped and bounced for a quarter-mile before taking to the air and then climbed very slowly indeed, for several minutes. Our speed was a scant two hundred miles an hour when we swung out over New York and headed for the Atlantic. And then Hart made first use of the rocket tubes, not daring to discharge the hot gases below while over populated land at so low an altitude. He touched one button, maintaining the pressure for but a fraction of a second. The ocean slipped more rapidly away from beneath our feet and he touched the button once more. Our speed was now nearly seven hundred miles an hour and we made haste to buckle ourselves into the padded, hammocklike contrivances which had been substituted for the former seats. In a very few minutes we entered level six and the motor was cut off entirely.

A blast from a number of the tail rockets drove me into my supporting hammock so heavily that I found difficulty in breathing, and could scarcely move a muscle to change position. The rate of acceleration was terrific, and I am still unable to understand how Hart was able to manipulate the controls. For myself, I could not even turn my head from its position in the padding and I felt as if I were being crushed by thousands of tons of pressure. Then, the pressure was somewhat relieved and I glanced to the instruments. We were more than a thousand miles from our starting point and the speed indicator read seven thousand miles an hour. We were traveling at the rate of nearly two miles a second!

Another blast from the rockets, this one of interminable length, and I must have lost consciousness. For when I next took note of things I found that we had been out for nearly two hours and that the tremendous pressure of acceleration was relieved. I moved my head, experimentally and found that my senses were normal, though there was a strange and alarming sensation of being wrong side up. Then I remembered that I had experienced the same thing when we first searched the upper levels of the atmosphere for the origin of the destructive rays of the enemy.

But this was different! I gazed through a nearby port and saw that the sky was entirely black, the stars shining magnificently brilliant against their velvet background. Streamers of brilliant sunlight from the floor ports struck across the cabin and patterned the ceiling. Looking between my feet I saw the sun as a flaming orb with streamers of incandescence that spread in every direction with such blinding luminosity that I could not bear the sight for more than a few seconds. Off to what I was pleased to think of as our left side, there was a huge globe that I quickly made out as our own earth. Eerily green it shone, and, though a considerable portion of the surface was obscured by patches of white that I recognized as clouds, I could clearly make out the continents of the eastern hemisphere. It was a marvelous sight and I lost several minutes in awed contemplation of the wonder. Then I heard Hart laugh.

"Just coming out of it, Jack?" he asked.

I stared at him foolishly. It had seemed to me that I was alone in this vast universe, and the sound of his voice startled me. "Guess I'm not fully out of it yet," I said. "Where are we?"

"Oh, about sixty thousand miles out," he replied carelessly; "and we are traveling at our maximum speed—that is, the maximum we need for this little voyage."

"Little voyage!" I gasped. And then I looked at George and the professor and saw that they, too, were grinning at my discomfiture. I laughed crazily, I suppose, for they all sobered at once.

Traveling through space at more than forty thousand miles an hour, it seemed that we were stationary. Move[Pg 77]ment was now easy—too easy, in fact, for we were practically weightless. The professor was having a time of it manipulating a pencil and a pad of paper on which he had a mass of small figures that were absolutely meaningless to me. He was calculating and plotting our course and, without him, we should never have reached the object we sought.

Time passed rapidly, for the wonders of the naked universe were a never-ending source of fascination. Occasionally a series of rocket charges was fired to keep our direction and velocity, but these were light, and the acceleration so insignificant that we were put to no discomfort whatever. But it was necessary that we keep our straps buckled, for, in the weightless condition, even the slightest increase or decrease in speed or change in direction was sufficient to throw us the length of the cabin, from which painful bruises might be received.

The supports to which we were strapped and which saved us from being crushed by the acceleration and deceleration, were similar to hammocks, being hooked to the floor and ceiling of the cabin rather than suspended horizontally in the conventional manner. This was for the reason that the energy of the rockets was expended fore and aft, except for steering, and the forces were therefore along the horizontal axis of the vessel. The supports were elastic and the padding deep and soft. Being swiveled at top and bottom, they could swing around so that deceleration as well as acceleration was relieved. For this reason the controls had been altered so that the flexible support in which Hart was suspended could rotate about their pedestal, thus allowing for their operation by the pilot either when accelerating or decelerating. How he could control the muscles of his arms and hands under the extreme conditions is still a mystery to me, however, and George agrees with me in this. We found ourselves to be utterly helpless.

My next impression of the trip is that of swinging rapidly around and finding myself facing the rear wall of the cabin. Then the tremendous pressure once more at a burst from the forward tubes. We had commenced deceleration. For me there were alternate periods of full and semi-consciousness and, to this day, I can remember no more than the high spots of that historical expedition.

Then we were free to move once more, and I turned to face the instrument board. Our relative velocity had become practically zero; that is, we were traveling through space at about the same speed and in the same direction as the earth. The professor and Hart were consulting a pencil chart and excitedly looking first through the forward ports and then into the screen of the periscope.

"This is the approximate location," averred the professor.

"But they are not here," replied Hart.

George and I peered in all directions and could see nothing excepting the marvels of the universe we had been viewing. The moon now seemed very close and its craters and so-called seas were as plainly visible as in a four-inch telescope on earth. But we saw nothing of the enemy.

The earth was a huge ball still, but much smaller than when I had first observed it from the heavens. The sun's corona—the flaming streamers which the professor declared extended as much as five million miles into space—was partly hidden behind the rim of the earth and the effect was blinding. A thin crescent of brilliant light marked the rim of our planet and the rest was in shadow, but a shadow that was lighted awesomely in cold green by reflected light from her satellite.

"I have it!" suddenly shouted the professor. "We are all in very nearly the same line with reference to the sun, and the enemy is between the blazing[Pg 78] body and ourselves. We must shift our position, move into the shadow of the earth. We have missed our calculation by a few hundred miles, that is all."

All! I thought. These astronomers, so accustomed to dealing in tremendous distances that must be measured in light-years, thought nothing of an error of several hundred miles. But I suppose it was really an inconsiderable amount, at that.

At any rate, we shifted position and looked around a bit more. We saw nothing at first. Then Hart consulted the chronometer.

"Time is up!" he shouted.

On the instant there was a flash of dazzling green light from a point not a hundred miles from our position, a flash that was followed by a streaking pencil of the same light shooting earthward with terrific velocity. Breathlessly we followed its length, saw it burst like a bomb and hurl three green balls from itself which sped at equally spaced angles to form a perfect triangle. They hovered a moment at about two thousand miles above the surface of the earth, according to the professor, who was using the telescope at the time, and shot their deadly rays toward our world. We were too late to prevent the renewal of hostilities!

Another and another streak of green light followed and we knew that great havoc was being wrought back home. But these served to locate the enemy's position definitely and we immediately set about to draw nearer. We were still somewhat on the dark side

Comments (0)