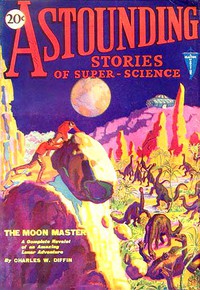

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 by Various (novels to improve english TXT) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 by Various (novels to improve english TXT) 📗». Author Various

[240] And all this while—or, rather, until the telegraph wires were cut—broken, it was discovered later, by perching beetles—Thomas Travers was sending out messages from his post at Settler's Station.

Soon it was known that prodigious creatures were following in the wake of the devastating horde. Mantises, fifteen feet in height, winged things like pterodactyls, longer than bombing airplanes, followed, preying on the stragglers. But the main bodies never halted, and the inroads that the destroyers made on their numbers were insignificant.

Before the swarm reached Adelaide the Commonwealth Government had taken action. Troops had been called out, and all the available airplanes in the country had been ordered to assemble at Broken Hill, New South Wales, a strategic point commanding the approaches to Sydney and Melbourne. Something like four hundred airplanes were assembled, with several batteries of anti-aircraft guns that had been used in the Great War. Every amateur aviator in Australia was on the spot, with machines ranging from tiny Moths to Handley-Pages—anything that could fly.

Nocturnal though the beetles had been, they no longer feared the light of the sun. In fact, it was ascertained later that they were blind. An opacity had formed over the crystalline lens of the eye. Blind, they were no less formidable than with their sight. They existed only to devour, and their numbers made them irresistible, no matter which way they turned.

As soon as the vanguard of the dark cloud was sighted from Broken Hill, the airplanes went aloft. Four hundred planes, each armed with machine guns, dashed into the serried hosts, drumming out volleys of lead. In a long line, extending nearly to the limits of the beetle formation, thus giving each aviator all the room he needed, the planes gave battle.

The first terror that fell upon the airmen was the discovery that, even at close range, the machine gun bullets failed to penetrate the shells. The force of the impact whirled the beetles around, drove them together in bunches, sent them groping with weaving tentacles through the air—but that was all. On the main body of the invaders no impression was made whatever.

The second terror was the realization that the swarm, driven down here and there from an altitude of several hundred feet, merely resumed their progress on the ground, in a succession of gigantic leaps. Within a few minutes, instead of presenting an inflexible barrier, the line of airplanes was badly broken, each plane surrounded by swarms of the monsters.

Then Bram was seen. And that was the third terror, the sight of the famous beetle steeds, four pairs abreast, with Bram reclining like a Roman emperor upon the surface of the shells. It is true, Bram had no inclination to risk his own life in battle. At the first sight of the aviators he dodged into the thick of the swarm, where no bullet could reach him. Bram managed to transmit an order, and the beetles drew together.

Some thought afterward that it was by thought transference he effected this maneuver, for instantly the beetles, which had hitherto flown in loose order, became a solid wall, a thousand feet in height, closing in on the planes. The propellers struck them and snapped short, and as the planes went weaving down, the hideous monsters leaped into the cockpits and began their abominable meal.

Not a single plane came back. Planes and skeletons, and here and there a shell of a dead beetle, itself completely devoured, were all that was found afterward.

The gunners stayed at their posts till the last moment, firing round after round of shell and shrapnel, with in[241]significant results. Their skeletons were found not twenty paces from their guns—where the Gunners' Monument now stands.

Half an hour after the flight had first been sighted the news was being radioed to Sydney, Melbourne, and all other Australian cities, advising instant flight to sea as the only chance of safety. That radio message was cut short—and men listened and shuddered. After that came the crowding aboard all craft in the harbors, the tragedies of the Eustis, the All Australia, the Sepphoris, sunk at their moorings. The innumerable sea tragedies. The horde of fugitives that landed in New Zealand. The reign of terror when the mob got out of hand, the burning of Melbourne, the sack of Sydney.

And south and eastward, like a resistless flood, the beetle swarm came pouring. Well had Bram boasted that he would make the earth a desert!

A hundred miles of poisoned carcasses of sheep, extended outside Sydney's suburbs, gave the first promise of success. Long mounds of beetle shells testified to the results; moreover, the beetles that fed on the carcasses of their fellows, were in turn poisoned and died. But this was only a drop in the bucket. What counted was that the swift advance was slowing down. As if exhausted by their efforts, or else satiated with food, the beetles were doing what the soldiers did.

They were digging in!

Twenty-four miles from Sydney, eighteen outside Melbourne, the advance was stayed.

Volunteers who went out from those cities reported that the beetles seemed to be resting in long trenches that they had excavated, so that only their shells appeared above ground. Trees were covered with clinging beetles, every wall, every house was invisible beneath the beetle armor.

Australia had a respite. Perhaps only for a night or day, but still time to draw breath, time to consider, time for the shiploads of fugitives to get farther from the continent that had become a shambles.

And then the cry went up, not only from Australia, but from all the world, "Get Travers!"

CHAPTER XAt Bay

Bram put his fingers to his mouth and whistled, a shrill whistle, yet audible to Dodd, Tommy, and Haidia. Instantly three pairs of beetles appeared out of the throng. Their tentacles went out, and the two men and the girl found themselves hoisted separately upon the backs of the pairs. Next moment they were flying side by side, high in the air above the surrounding swarm.

They could see one another, but it was impossible for them to make their voices heard above the rasping of the beetles' legs. Hours went by, while the moon crossed the sky and dipped toward the horizon. Tommy knew that the moon would set about the hour of dawn. And the stars were already beginning to pale when he saw a line of telegraph poles, then two lines of shining metals, then a small settlement of stone and brick houses.

Tommy was not familiar with the geography of Australia, but he knew this must be the transcontinental line.

Whirling onward, the cloud of beetles suddenly swooped downward. For a moment Tommy could see the frightened occupants of the settlement crowding into the single street, then he shuddered with sick horror as he saw them obliterated by the swarm.

There was no struggle, no attempt at flight or resistance. One moment those forty-odd men were there—the next minute they existed no longer. There was nothing but a swarm of beetles, walking about like men with shells upon their backs.

And now Tommy saw evidences of Bram's devilish control of the swarm.[242] For out of the cloud dropped what seemed to be a phalanx of beetle guards, the military police of beetledom, and, lashing fiercely with their tentacles, they drove back all the swarm that sought to join their companions in their ghoulish feast. There was just so much food and no more; the rest must seek theirs further.

But even beetles, it may be presumed, are not entirely under discipline at all times. The pair of beetles that bore Tommy, suddenly swooped apart, ten or a dozen feet from the ground, and dashed into the thick of the struggling, frenzied mass, flinging their rider to earth.

Tommy struck the soft sand, sat up, half dazed, saw his shell lying a few feet away from him, and retrieved it just as a couple of the monsters came swooping down at him.

He looked about him. Not far away stood Dodd and Haidia, with their shells on their backs. They recognized Tommy and ran toward him.

Not more than twenty yards away stood the railroad station, with several crates of goods on the platform. Next to it was a substantial house of stone, with the front door open.

Tommy pointed to it, and Dodd understood and shouted something that was lost in the furious buzz of the beetles' wings as they devoured their prey. The three raced for the entrance, gained it unmolested, and closed the door.

There was a key in the door, and it was light enough for them to see a chain, which Dodd pulled into position. There was only one story, and there were three rooms, apparently, with the kitchen. Tommy rushed to the kitchen door, locked it, too, and, with almost super-human efforts, dragged the large iron stove against it. He rushed to the window, but it was a mere loophole, not large enough to admit a child. Nevertheless, he stood the heavy table on end so that it covered it. Then he ran back.

Dodd had already barricaded the window of the larger room, which was a bed-sitting room, with a heavy wardrobe, and the wooden bedstead, jamming the two pieces sidewise against the wall, so that they could not be forced apart without being demolished. He was now busy in the smaller room, which seemed to be the station-master's office, dragging an iron safe across the floor. But the window was criss-crossed with iron bars, and it was evident that the safe, which was locked, contained at times considerable money, for the window could hardly have been forced save by a charge of nitro-glycerine or dynamite. However, it was against the door that Dodd placed the safe, and he stood back, panting.

"Good," said Haidia. "That will hold them."

The two men looked at her doubtfully. Did Haidia know what she was talking about?

The sun had risen. A long shaft shot into the room. Outside the beetles were still buzzing as they turned over the vestiges of their prey. There were as yet no signs of attack. Suddenly Tommy grasped Dodd's arm.

"Look!" he shouted, pointing to a corner which had been in gloom a moment before.

There was a table there, and on it a telegraphic instrument. Telegraphy had been one of Tommy's hobbies in boyhood. In a moment he was busy at the table.

Dot-dash-dot-dash! Then suddenly outside a furious hum, and the impact of beetle bodies against the front door.

Tommy got up, grinning. That was the first, interrupted message from Tommy that was received.

Through the barred window the three could see the furious efforts of the beetles to force an entrance. But the very tensile strength of the beetle-shells, which rendered them impervious to bullets, required a laminate construc[243]tion which rendered them powerless against brick or stone.

Desperately the swarm dashed itself against the walls, until the ground outside was piled high with stunned beetles. Not the faintest impression was made on the defenses.

"Watch them, Jim," said Tom. "I'll go see if the rear's secure."

That thought of his seemed to have been anticipated by the beetles, for as Tommy reached the kitchen the swarm came dashing against door and window, always recoiling. Tommy came back, grinning all over his face.

"You were right, Haidia," he said. "We've held them all right, and the tables are turned on Bram. Also I got a message through, I think," he added to Dodd.

Dash—dot—dash—dot from the instrument. Tommy ran to the table again. Dash—dot went back. For five minutes Tommy labored, while the beetles hammered now on one door, now on another, now on the windows. Then Tommy got up.

"It was some station down the line," he said. "I've told them, and they're sending a man up here to replace the telegraphist, also a couple of cops. They think I'm crazy. I told them again. That's the best I could do."

"Dodd! Travers! For the last time—let's talk!"

The cloud of beetles seemed to have thinned, for the sun was shining into the room. Bram's voice was perfectly audible, though he himself was invisible; probably he thought it likely that the defenders had obtained firearms.

"Nothing to say to you, Bram," called Dodd. "We've finished our discussion on the monotremes."

"I want you fellows to stand in with me," came Bram's plaintive tones. "It's so lonesome all by one's self, Dodd."

"Ah, you're beginning to find that out, are you?" Dodd could not resist answering. "You'll be lonelier yet before you're through."

"Dodd, I didn't bring that swarm up here. I swear it. I've been trying to control them from the beginning. I saw what was coming. I believe I can avert this horror, drive them into the sea or something like that. Don't make me desperate, Dodd.

"And listen, old man. About those monotremes—sensible men don't quarrel over things like that. Why can't we agree to differ?"

"Ah, now you're talking, Bram," Dodd answered. "Only you're too late. After what's happened here to-day, we'll have no truck with you. That's final."

"Damn you," shrieked Bram. "I'll batter down this house. I'll—"

"You'll do nothing, Bram, because you can't," Dodd answered. "Travers has wired full information about your devil-horde, and likewise about you, and all Australia will be prepared to give you a warm reception when you arrive."

"I tell you I'm invincible," Bram screamed. "In three days Australia will be a ruin, a depopulated desert. In a week, all southern Asia, in three weeks Europe, in two months America."

"You've been taking too many of those pellets, Bram," Dodd answered. "Stand back now! Stand back, wherever you are, or I'll open the door and throw the slops over you."

Bram's screech rose high above the droning of the wings. In another moment the interior of the room had grown as black as night. The rattle of the beetle

Comments (0)