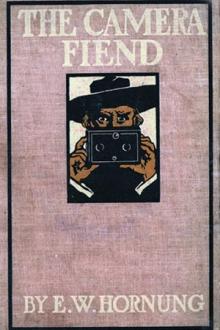

The Camera Fiend - E. W. Hornung (books you need to read txt) 📗

- Author: E. W. Hornung

- Performer: -

Book online «The Camera Fiend - E. W. Hornung (books you need to read txt) 📗». Author E. W. Hornung

Yet if anybody had told the boy he was beginning to gloat over the silver lining to the cloud that he was under, and that it was not silver at all but one of the baser metals of the human heart, how indignantly he would have denied it at first, how humbly seen it in the end!

When Phillida went off to make the tea her uncle sought his room and sponge, but did not neglect to take Pocket with him. Pocket was for going higher up to his own room; but Baumgartner said that would only make more work, in a tone [pg 188] precluding argument. It struck Pocket that the doctor really needed sleep, and was irritable after a continuous struggle against it. If so, it served him right for not trusting a fellow—and for putting Boismont in the waste-paper basket, by Jove!

There was no mistaking the red book there; it was one of the first things Pocket noticed, while the doctor was stooping over his basin in the opposite corner; and the schoolboy's strongest point, be it remembered, was a stubborn tenacity of his own devices. He made a dive at the waste-paper basket, meaning to ask afterwards if the doctor minded his reading that book. But the question never was asked; the book was still in the basket when the doctor had finished drying his face; and the boy was staring and swaying as though he had seen the dead.

“Why, what's the matter with my young fellow?” inquired Baumgartner, solicitously.

“Nothing! I'll be all right soon,” muttered Pocket, wiping his forehead and then his hand.

“You look faint. Here's my sponge. No, lie flat down there first!”

But Pocket was not going to lie down on that bed.

“I do feel seedy,” he said, in a stronger voice with a new note in it, “but I'm not going to faint. I'm quite well able to go upstairs. I'd rather lie down on my own bed, if you don't mind.”

[pg 189]His own bed! The irony struck him even as he said the words. He was none the less glad to sit down on it; and so sitting he made his first close examination of two or three tiny squares of paper which he had picked out of the basket in the doctor's room instead of Boismont's book on hallucinations. There had been no hallucination about those scraps of paper; they were fragments of the boy's own letter to his sister, which Dr. Baumgartner had never posted at all.

At that moment help was as far away as it had been near the day before, when Eugene Thrush was closeted in the doctor's dining-room; for not only had Mr. Upton decamped for Leicestershire, without a word of warning to anybody, on the Saturday afternoon, but Thrush himself had followed by the only Sunday train.

A bell was ringing for evening service when he landed in a market town which reversed the natural order by dozing all summer and waking up for the hunting season. And now the famous grass country was lying in its beauty-sleep, under a gay counterpane of buttercups and daisies, and leafy coverts, [pg 190] with but one blot in the sky-line, in the shape of a permanent plume of sluggish smoke. But the works lay hidden, and the hall came first; and Thrush, having ascertained that this was it, abandoned the decrepit vessel he had boarded at the station, and entered the grounds on foot.

A tall girl, pacing the walks with a terribly anxious face, was encountered and accosted before he reached the house.

“I believe Mr. Upton lives here. Can you tell me if he's at home? I want to see him about something.”

Lettice flushed and shrank.

“I know who you are! Have you found my brother?”

“No; not yet,” said Thrush, after a pause. “But you take my breath away, my dear young lady! How could you be so sure of me? Is it no longer to be kept a secret, and is that why your father bolted out of town without a word?”

“It's still a secret,” whispered Lettice, as though the shrubs had ears, “only I'm in it. Nobody else is—nobody fresh—but I guessed, and my mother was beginning to suspect. My father never stays away a Sunday unless he's out of England altogether; she couldn't understand it, and was worrying so about him that I wired begging him to come back if only for the night. So it's all my [pg 191] fault, Mr. Thrush; and I know everything but what you've come down to tell us!”

“That's next to nothing,” he shrugged. “It's neither good nor bad. But if you can find your father I'll tell you both exactly what I have found out.”

In common with all his sex, he liked and trusted Lettice at sight, without bestowing on her a passing thought as a person capable of provoking any warmer feeling. She was the perfect sister—that he felt as instinctively as everybody else—and a woman to trust into the bargain. It would be cruel and quite unnecessary to hide anything from that fine and unselfish face. So he let her lead him to a little artificial cave, lined and pungent with pitch-pine, over against the rhododendrons, while she went to fetch her father quietly from the house.

The ironmaster amplified the excuses already made for him; he had rushed for the first train after getting his daughter's telegram, leaving but a line for Thrush with his telephone number, in the hopes that he would use it whether he had anything to report or not.

“As you didn't,” added Mr. Upton, in a still aggrieved voice, “I've been trying again and again to ring you up instead; but of course you were never there, nor your man Mullins either. I was [pg 192] coming back by the last train, however, and should have been with you late to-night.”

“Did you leave the motor behind?”

“Yes; it'll be there to meet me at St. Pancras.”

“It may have to do more than that,” said Thrush, spreading his full breadth on the pitch-pine seat. “I've found out something; how much or how little it's too soon to tell; but I wasn't going to discuss it through a dozen country exchanges as long as you wanted the thing a dead secret, Mr. Upton, and that's why I didn't ring you up. As for your last train, I'd have waited to meet it in town, only that wouldn't have given me time to say what I've got to say before one or other of us may have to rush off somewhere else by another last train.”

“Do for God's sake say what you've got to say!” cried Mr. Upton.

“Well, I've seen a man who thinks he may have seen the boy!”

“Alive?”

“And perfectly well—but for his asthma—on Thursday.”

The ironmaster thanked God in a dreadful voice; it was Lettice who calmed him, not he her. Her eyes only shone a little, but his were blinded by the first ray of light.

“Where was it?” he asked, when he could ask anything.

[pg 193]“I'll tell you in a minute. I want first to be convinced that it really was your son. Did the boy take any special interest in Australia?”

“Rather!” cried Lettice, the sister of three boys.

“What kind of interest?”

“He wanted to go out there. It had just been talked about.” She looked at her father. “I wouldn't let him go,” he said. “Why?”

“I want to know just how it came to be talked about.”

“A fool of a doctor in town recommended it.”

Lettice winced, but Thrush nodded as though that tallied.

“Did he recommend any particular vessel?”

“Yes, a sailing ship—the Seringapatam— an old East Indiaman they've turned into a kind of floating hospital. I wouldn't hear of the beastly tub.”

“Do you know when she was to sail?”

“I did know,” said Lettice. “I believe it was just about now.”

“She sailed yesterday,” said Thrush, impressively; “and your brother, if it was your brother, talked a good deal about her to this man. He told him all about your having always been in favour of it, Miss Upton, and his father not. I'm bound to say it sounds as though it may have been the boy.”

[pg 194]Thrush seemed to be keeping something back; but the prime and absorbing question of identity prevented the others from noticing this.

“It must have been!” cried Mr. Upton. “Who was the man, and where exactly did he see him?”

“First on Thursday morning, and last on Thursday night. But perhaps I'd better tell you about my informant, since we've only his word for Thursday, and only his suspicions as to what has happened since. In the first place he's a semi-public man, though I don't suppose you know his name. It's Baumgartner—Dr. Otto Baumgartner—a German scientist of some distinction.”

The ironmaster made a remark which did him little credit, and Thrush continued with some pride: “There was some luck in it, of course, for he was the very first man I struck who'd bought d'Auvergne Cigarettes since Wednesday; but I was on his doorstep well within twenty-four hours of hearing that your son was missing; and you may chalk that up to A. V. M.! I might have been with him some hours sooner still, but I preferred to spend them getting to know something about my man. I tried his nearest shops; perfect mines! One was a chemist, who didn't know him by sight, and had never heard of the cigarettes, but remembered being asked for them by an elderly gentleman last Thursday morning! That absolutely confirmed [pg 195] my first suspicion that Baumgartner himself was not the asthmatic; if he had been, the nearest chemist would have known all about him.

Comments (0)