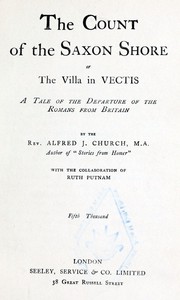

The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (fantasy books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Church and Putnam

Book online «The Count of the Saxon Shore; or The Villa in Vectis.<br />A Tale of the Departure of the Romans fro by Church and Putnam (fantasy books to read TXT) 📗». Author Church and Putnam

The mother said nothing. If she did not exactly see the whole of the situation, she had at least an housewife’s horror of a move. The poor father moved uneasily upon his chair.

“The legion will go,” he said, “but your mother and you——”

“Oh, Lucius,” cried the poor wife, “you do not, cannot mean that we are not to go with you!”

“Nothing is settled,” he replied, “it is true; but I am much troubled about it. You might go, though I do not like the idea of your following the camp; but these dear girls—and yet they cannot be separated from you.”

The unhappy wife saw the truth only too clearly. If the times had been quiet, she might herself have possibly accompanied the legion in its march southward; but even then she could not have taken her daughters with her, her daughters whom she never allowed to go within the precincts of the camp, except on the one day, the Emperor’s birthday, when all the officers’ families were expected to be present at the ceremony of saluting the Imperial likeness. And this had of late been omitted when it was difficult to say from day to day what Emperor the troops acknowledged. The centurion had spoken only too truly; the legion might go, but they must [pg 89]stay behind. She covered her face with her hands and wept.

“Lucia,” cried the elder girl to her sister, “we will enlist; we will take the oath; I should make just as good a soldier as many of the Briton lads they are filling up the cohorts with now; though you, I must allow, are a little too small,” she added, ruefully, as she looked at her sister’s plump little figure, too hopelessly feminine ever to admit the possibility of a disguise. “Cheer up, mother,” she went on, “we shall find a way out of the difficulty somehow.” And she threw her arms round the weeping woman, and kissed her repeatedly.

There was silence for a few minutes, broken at last by the timid, hesitating voice of the younger girl.

“But must you go, father?” she said. “Surely they don’t keep soldiers in the camp for ever. And have you not served long enough? You were in the legion, I have heard you say, before even Maria was born.”

“My child,” said the centurion, “it is true that my time is at least on the point of being finished. Yet I can’t leave the service just now. Just because I am the oldest officer the Legate counts on me, and I can’t desert him. It would be almost as bad as asking for one’s discharge on the eve of a battle. And besides, though I don’t like troubling your young spirits with such matters, I cannot afford it. [pg 90]Were I to resign now I should get no pension, or next to none. But in a year or two’s time, when things are settled down, I hope to get something worth having—some post, perhaps, that would give me a chance of making a home for you.”

A fifth person, who had hitherto taken no part in the conversation, and whose presence in the room had been almost forgotten by every one, now broke in, with a voice which startled the hearers by its unusual clearness and precision. Lena, mother of the centurion’s wife, had nearly completed her eightieth year. Commonly, she sat in the chimney corner, unheeding, to all appearances, of the life that went on about her, and dozing away the day. In her prime, and even down to old age, she had been a woman of remarkable activity, ruling her daughter’s household as despotically as in former days she had ruled her own. Then a sudden and severe illness had prostrated her, and she had seemed to shrink at once into feebleness and helplessness of mind and body. Her daughter and granddaughters tended her carefully and lovingly; but she seemed scarcely to take any notice of them. The only thing that ever seemed to rouse her attention was the sight of her son-in-law when he chanced to enter the chamber without disarming. The shine of the steel brought a fire again into her dim, sunken eyes. It was probably this that had now roused her; and her [pg 91]attention, once awakened, had been kept alive by what she heard.

“And at whose bidding are you going?” she said, in a startlingly clear voice to come from one so feeble; “this Honorius, as he calls himself, a feeble creature who has never drawn a sword in his life! Now, if it had been his father! He was a man to obey. He did deserve to be called Emperor. I saw him forty years ago—just after you were born, daughter—when he came with his father. A splendid young fellow he was; and one who would have his own way, too! How he gave those turbulent Greeks at Thessalonica their deserts! Fifteen thousand of them!29 That was an Emperor worth having!”

“Oh! mother,” cried her daughter, horrified to see the old woman’s ferocity, softened, she had hoped, by age and infirmity, roused again in all its old strength. “Oh! mother, don’t say such dreadful things. That was an awful crime in Theodosius, and he had to do penance for it in the church.”

“Ay,” muttered the old woman, “I can fancy it did not please the priests. But why,” she went on, raising her voice again, “why does not Britain have an Emperor of her own?”

[pg 92]“So she has, mother,” said the centurion. “You forget our Lord Constantine.”

“Our Lord Constantine!” she repeated. “Who is Constantine? Why, I remember his mother—a slave girl—whom the Irish pirates carried off from somewhere in the North. Constantine’s father bought her, and married her. Why should he be

Comments (0)