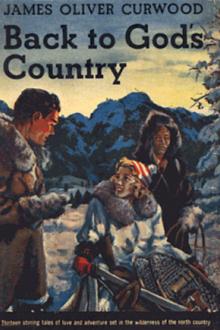

God's Country - And the Woman - James Oliver Curwood (best classic romance novels .txt) 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

Book online «God's Country - And the Woman - James Oliver Curwood (best classic romance novels .txt) 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

invite me to go with you?"

"It was a part of our night's business to be alone," responded Jean. "Josephine was with me. She is in her room now with the baby."

"Does Adare know you have returned?"

"Josephine has told him. He is to believe that I went out to see a trapper over on the Pipestone."

"It is strange," mused Philip, speaking half to himself. "A strange reason indeed it must be to make Josephine say these false things."

"It is like driving sharp claws into her soul," affirmed Jean.

"I believe that I know something of what happened to-night, Jean. Are we any nearer to the end--to the big fight?"

"It is coming, M'sieur. I am more than ever certain of that. The third night from this will tell us."

"And on that night--"

Philip waited expectantly.

"We will know," replied Jean in a voice which convinced him that the half-breed would say no more. Then he added: "It will not be strange if Josephine does not go with you on the sledge-drive to-morrow, M'sieur. It will also be curious if there is not some change in her, for she has been under a great strain. But make as if you did not see it. Pass your time as much as possible with the master of Adare. Let him not guess. And now I am going to ask you to let me go to bed. My head aches. It is from the blow."

"And there is nothing I can do for you, Jean?'

"Nothing, M'sieur."

At the door Philip turned.

"I have got a grip on myself now, Jean," he said. "I won't fail you. I'll do as you say. But remember, we are to have the fight at the end!"

In his room he sat up for a time and smoked. Then he went to bed. Half a dozen times during the night he awoke from a restless slumber. Twice he struck a match to look at his watch. It was still dark when he got up and dressed. From five until six he tried to read. He was delighted when Metoosin came to the door and told him that breakfast would be ready in half an hour. This gave him just time to shave.

He expected to eat alone with Adare again this morning, and his heart jumped with both surprise and joy when Josephine came out into the hall to meet him. She was very pale. Her eyes told him that she had passed a sleepless night. But she was smiling bravely, and when she offered him her hand he caught her suddenly in his arms and held her close to his breast while he kissed her lips, and then her shining hair.

"Philip!" she protested. "Philip--"

He laughed softly, and for a moment his face was close against hers.

"My brave little darling! I understand," he whispered. "I know what a night you've had. But there's nothing to fear. Nothing shall harm you. Nothing shall harm you, nothing, nothing!"

She drew away from him gently, and there was a mist in her eyes. But he had brought a bit of colour into her face. And there was a glow behind the tears. Then, her lip quivering, she caught his arm.

"Philip, the baby is sick--and I am afraid. I haven't told father. Come!"

He went with her to the room at the end of the hall. The Indian woman was crooning softly over a cradle. She fell silent as Josephine and Philip entered, and they bent over the little flushed face on the pillow. Its breath came tightly, gaspingly, and Josephine clutched Philip's hand, and her voice broke in a sob.

"Feel, Philip--its little face--the fever--"

"You must call your mother and father," he said after a moment. "Why haven't you done this before, Josephine?"

"The fever came on suddenly--within the last half hour," she whispered tensely. "And I wanted you to tell me what to do, Philip. Shall I call them--now?"

He nodded.

"Yes."

In an instant she was out of the room. A few moments later she returned, followed by Adare and his wife. Philip was startled by the look that came into Miriam's face as she fell on her knees beside the cradle. She was ghastly white. Dumbly Adare stood and gazed down on the little human mite he had grown to worship. And then there came through his beard a great broken breath that was half a sob.

Josephine lay her cheek against his arm for a moment, and said:

"You and Philip go to breakfast, Mon Pere. I am going to give the baby some of the medicine the Churchill doctor left with me. I was frightened at first. But I'm not now. Mother and I will have him out of the fever shortly."

Philip caught her glance, and took Adare by the arm. Alone they went into the breakfast-room. Adare laughed uneasily as he seated himself opposite Philip.

"I don't like to see the little beggar like that," he said, taking to shake off his own and Philip's fears with a smile. "It was Mignonne who scared me--her face. She has nursed so many sick babies that it frightened me to see her so white. I thought he might be--dying."

"Cutting teeth, mebby," volunteered Philip.

"Too young," replied Adare.

"Or a touch of indigestion, That brings fever."

"Whatever it is, Josephine will soon have him kicking and pulling my thumb again," said Adare with confidence. "Did she ever tell you about the little Indian baby she found in a tepee?"

"No."

"It was in the dead of winter. Mignonne was out with her dogs, ten miles to the south. Captain scented the thing--the Indian tepee. It was abandoned--banked high with snow--and over it was the smallpox signal. She was about to go on, but Captain made her go to the flap of the tepee. The beast knew, I guess. And Josephine--my God, I wouldn't have let her do it for ten years of my life! There had been smallpox in that tent; the smell of it was still warm. Ugh! And she looked in! And she says she heard something that was no louder than the peep of a bird. Into that death-hole she went--and brought out a baby. The parents, starving and half crazed after their sickness, had left it--thinking it was dead.

"Josephine brought it to a cabin close to home, in two weeks she had that kid out rolling in the snow. Then the mother and father heard something of what had happened, and came to us as fast as their legs could bring them. You should have seen that Indian mother's gratitude! She didn't think it so terrible to leave the baby unburied. She thought it was dead. Pasoo is the Indian father's name. Several times a year they come to see Josephine, and Pasoo brings her the choicest furs of his trap-line. And each time he says: 'Nipa tu mo-wao,' which means that some day he hopes to be able to kill for her. Nice, isn't it--to have friends who'll murder your enemies for you if you just give 'em the word?"

"One never can tell," began Philip cautiously. "A time might come when she would need friends. If such a day should happen--"

He paused, busying himself with his steak. There was a note of triumph, of exultation, in Adare's low laugh.

"Have you ever seen a fire run through a pitch-dry forest?" he asked. "That is the way word that Josephine wanted friends would sweep through a thousand square miles of this Northland. And the answer to it would be like the answer of stray wolves to the cry of the hunt-pack!"

All over Philip there surged a warm glow.

"You could not have friends like that down there, in the cities," he said.

Adare's face clouded.

"I am not a pessimist," he answered, after a moment. "It has been one of my few Commandments always to look for the bright spot, if there is one. But, down there, I have seen so many wolves, human wolves. It seems strange to me that so many people should have the same mad desire for the dollar that the wolves of the forest have for warm, red, quivering flesh. I have known a wolf-pack to kill five times what it could eat in a night, and kill again the next night, and still the next--always more than enough. They are like the Dollar Hunters--only beasts. Among such, one cannot have solid friends--not very many who will not sell you for a price. I was afraid to trust Josephine down among them. I am glad that it was you she met, Philip. You were of the North--a foster-child, if not born there."

That day was one of gloom in Adare House. The baby's fever grew steadily worse, until in Josephine's eyes Philip read the terrible fear. He remained mostly with Adare in the big room. The lamps were lighted, and Adare had just risen from his chair, when Miriam came through the door. She was swaying, her hands reaching out gropingly, her face the gray of ash that crumbles from an ember. Adare sprung to meet her, a strange cry on his lips, and Philip was a step behind her. He heard her moaning words, and as he rushed past them into the hall he knew that she had fallen fainting into her husband's arms.

In the doorway to Josephine's room he paused. She was there, kneeling beside the little cradle, and her face as she lifted it to him was tearless, but filled with a grief that went to the quick of his soul. He did not need to look into the cradle as she rose unsteadily, clutching a hand at her heart, as if to keep it from breaking. He knew what he would see. And now he went to her and drew her close in his strong arms, whispering the pent-up passion of the things that were in his heart, until at last her arms stole up about his neck, and she sobbed on his breast like a child. How long he held her there, whispering over and over again the words that made her grief his own, he could not have told; but after a time he knew that some one else had entered the room, and he raised his eyes to meet those of John Adare. The face of the great, grizzled giant had aged five years. But his head was erect. He looked at Philip squarely. He put out his two hands, and one rested on Josephine's head, the other on Philip's shoulder.

"My children," he said gently, and in those two words were weighted the strength and consolation of the world.

He pointed to the door, motioning Philip to take Josephine away, and then he went and stood at the crib-side, his great shoulders hunched over, his head bowed down.

Tenderly Philip led Josephine from the room. Adare had taken his wife to her room, and when they entered she was sitting in a chair, staring and speechless. And now Josephine turned to Philip, taking his face between her two hands, and her soul looking at him through a blinding mist of tears.

"My Philip," she whispered, and drew his face down and kissed him. "Go to him now. We will come--soon."

He returned to Adare like one in a dream--a dream that was grief and pain, with its one golden thread of joy. Jean was there now, and the Indian woman; and the master of Adare had the still little babe huddled up against his breast. It was some time before they could induce him to give it to Moanne. Then, suddenly, he shook himself like a great bear, and crushed Philip's shoulders in his hands.

"God knows I'm sorry for you, Boy," he cried brokenly. "It's hurt me--terribly. But YOU--it must be like the

"It was a part of our night's business to be alone," responded Jean. "Josephine was with me. She is in her room now with the baby."

"Does Adare know you have returned?"

"Josephine has told him. He is to believe that I went out to see a trapper over on the Pipestone."

"It is strange," mused Philip, speaking half to himself. "A strange reason indeed it must be to make Josephine say these false things."

"It is like driving sharp claws into her soul," affirmed Jean.

"I believe that I know something of what happened to-night, Jean. Are we any nearer to the end--to the big fight?"

"It is coming, M'sieur. I am more than ever certain of that. The third night from this will tell us."

"And on that night--"

Philip waited expectantly.

"We will know," replied Jean in a voice which convinced him that the half-breed would say no more. Then he added: "It will not be strange if Josephine does not go with you on the sledge-drive to-morrow, M'sieur. It will also be curious if there is not some change in her, for she has been under a great strain. But make as if you did not see it. Pass your time as much as possible with the master of Adare. Let him not guess. And now I am going to ask you to let me go to bed. My head aches. It is from the blow."

"And there is nothing I can do for you, Jean?'

"Nothing, M'sieur."

At the door Philip turned.

"I have got a grip on myself now, Jean," he said. "I won't fail you. I'll do as you say. But remember, we are to have the fight at the end!"

In his room he sat up for a time and smoked. Then he went to bed. Half a dozen times during the night he awoke from a restless slumber. Twice he struck a match to look at his watch. It was still dark when he got up and dressed. From five until six he tried to read. He was delighted when Metoosin came to the door and told him that breakfast would be ready in half an hour. This gave him just time to shave.

He expected to eat alone with Adare again this morning, and his heart jumped with both surprise and joy when Josephine came out into the hall to meet him. She was very pale. Her eyes told him that she had passed a sleepless night. But she was smiling bravely, and when she offered him her hand he caught her suddenly in his arms and held her close to his breast while he kissed her lips, and then her shining hair.

"Philip!" she protested. "Philip--"

He laughed softly, and for a moment his face was close against hers.

"My brave little darling! I understand," he whispered. "I know what a night you've had. But there's nothing to fear. Nothing shall harm you. Nothing shall harm you, nothing, nothing!"

She drew away from him gently, and there was a mist in her eyes. But he had brought a bit of colour into her face. And there was a glow behind the tears. Then, her lip quivering, she caught his arm.

"Philip, the baby is sick--and I am afraid. I haven't told father. Come!"

He went with her to the room at the end of the hall. The Indian woman was crooning softly over a cradle. She fell silent as Josephine and Philip entered, and they bent over the little flushed face on the pillow. Its breath came tightly, gaspingly, and Josephine clutched Philip's hand, and her voice broke in a sob.

"Feel, Philip--its little face--the fever--"

"You must call your mother and father," he said after a moment. "Why haven't you done this before, Josephine?"

"The fever came on suddenly--within the last half hour," she whispered tensely. "And I wanted you to tell me what to do, Philip. Shall I call them--now?"

He nodded.

"Yes."

In an instant she was out of the room. A few moments later she returned, followed by Adare and his wife. Philip was startled by the look that came into Miriam's face as she fell on her knees beside the cradle. She was ghastly white. Dumbly Adare stood and gazed down on the little human mite he had grown to worship. And then there came through his beard a great broken breath that was half a sob.

Josephine lay her cheek against his arm for a moment, and said:

"You and Philip go to breakfast, Mon Pere. I am going to give the baby some of the medicine the Churchill doctor left with me. I was frightened at first. But I'm not now. Mother and I will have him out of the fever shortly."

Philip caught her glance, and took Adare by the arm. Alone they went into the breakfast-room. Adare laughed uneasily as he seated himself opposite Philip.

"I don't like to see the little beggar like that," he said, taking to shake off his own and Philip's fears with a smile. "It was Mignonne who scared me--her face. She has nursed so many sick babies that it frightened me to see her so white. I thought he might be--dying."

"Cutting teeth, mebby," volunteered Philip.

"Too young," replied Adare.

"Or a touch of indigestion, That brings fever."

"Whatever it is, Josephine will soon have him kicking and pulling my thumb again," said Adare with confidence. "Did she ever tell you about the little Indian baby she found in a tepee?"

"No."

"It was in the dead of winter. Mignonne was out with her dogs, ten miles to the south. Captain scented the thing--the Indian tepee. It was abandoned--banked high with snow--and over it was the smallpox signal. She was about to go on, but Captain made her go to the flap of the tepee. The beast knew, I guess. And Josephine--my God, I wouldn't have let her do it for ten years of my life! There had been smallpox in that tent; the smell of it was still warm. Ugh! And she looked in! And she says she heard something that was no louder than the peep of a bird. Into that death-hole she went--and brought out a baby. The parents, starving and half crazed after their sickness, had left it--thinking it was dead.

"Josephine brought it to a cabin close to home, in two weeks she had that kid out rolling in the snow. Then the mother and father heard something of what had happened, and came to us as fast as their legs could bring them. You should have seen that Indian mother's gratitude! She didn't think it so terrible to leave the baby unburied. She thought it was dead. Pasoo is the Indian father's name. Several times a year they come to see Josephine, and Pasoo brings her the choicest furs of his trap-line. And each time he says: 'Nipa tu mo-wao,' which means that some day he hopes to be able to kill for her. Nice, isn't it--to have friends who'll murder your enemies for you if you just give 'em the word?"

"One never can tell," began Philip cautiously. "A time might come when she would need friends. If such a day should happen--"

He paused, busying himself with his steak. There was a note of triumph, of exultation, in Adare's low laugh.

"Have you ever seen a fire run through a pitch-dry forest?" he asked. "That is the way word that Josephine wanted friends would sweep through a thousand square miles of this Northland. And the answer to it would be like the answer of stray wolves to the cry of the hunt-pack!"

All over Philip there surged a warm glow.

"You could not have friends like that down there, in the cities," he said.

Adare's face clouded.

"I am not a pessimist," he answered, after a moment. "It has been one of my few Commandments always to look for the bright spot, if there is one. But, down there, I have seen so many wolves, human wolves. It seems strange to me that so many people should have the same mad desire for the dollar that the wolves of the forest have for warm, red, quivering flesh. I have known a wolf-pack to kill five times what it could eat in a night, and kill again the next night, and still the next--always more than enough. They are like the Dollar Hunters--only beasts. Among such, one cannot have solid friends--not very many who will not sell you for a price. I was afraid to trust Josephine down among them. I am glad that it was you she met, Philip. You were of the North--a foster-child, if not born there."

That day was one of gloom in Adare House. The baby's fever grew steadily worse, until in Josephine's eyes Philip read the terrible fear. He remained mostly with Adare in the big room. The lamps were lighted, and Adare had just risen from his chair, when Miriam came through the door. She was swaying, her hands reaching out gropingly, her face the gray of ash that crumbles from an ember. Adare sprung to meet her, a strange cry on his lips, and Philip was a step behind her. He heard her moaning words, and as he rushed past them into the hall he knew that she had fallen fainting into her husband's arms.

In the doorway to Josephine's room he paused. She was there, kneeling beside the little cradle, and her face as she lifted it to him was tearless, but filled with a grief that went to the quick of his soul. He did not need to look into the cradle as she rose unsteadily, clutching a hand at her heart, as if to keep it from breaking. He knew what he would see. And now he went to her and drew her close in his strong arms, whispering the pent-up passion of the things that were in his heart, until at last her arms stole up about his neck, and she sobbed on his breast like a child. How long he held her there, whispering over and over again the words that made her grief his own, he could not have told; but after a time he knew that some one else had entered the room, and he raised his eyes to meet those of John Adare. The face of the great, grizzled giant had aged five years. But his head was erect. He looked at Philip squarely. He put out his two hands, and one rested on Josephine's head, the other on Philip's shoulder.

"My children," he said gently, and in those two words were weighted the strength and consolation of the world.

He pointed to the door, motioning Philip to take Josephine away, and then he went and stood at the crib-side, his great shoulders hunched over, his head bowed down.

Tenderly Philip led Josephine from the room. Adare had taken his wife to her room, and when they entered she was sitting in a chair, staring and speechless. And now Josephine turned to Philip, taking his face between her two hands, and her soul looking at him through a blinding mist of tears.

"My Philip," she whispered, and drew his face down and kissed him. "Go to him now. We will come--soon."

He returned to Adare like one in a dream--a dream that was grief and pain, with its one golden thread of joy. Jean was there now, and the Indian woman; and the master of Adare had the still little babe huddled up against his breast. It was some time before they could induce him to give it to Moanne. Then, suddenly, he shook himself like a great bear, and crushed Philip's shoulders in his hands.

"God knows I'm sorry for you, Boy," he cried brokenly. "It's hurt me--terribly. But YOU--it must be like the

Free e-book «God's Country - And the Woman - James Oliver Curwood (best classic romance novels .txt) 📗» - read online now

Similar e-books:

Comments (0)