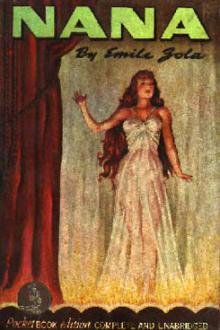

Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «Nana - Émile Zola (good books to read for young adults txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

bent on passing the evening there, and yet he was not quite happy.

Indeed, he kept tucking up his long legs in his endeavors to escape

from a whole litter of black kittens who were gamboling wildly round

them while the mother cat sat bolt upright, staring at him with

yellow eyes.

“Ah, it’s you, Mademoiselle Simonne! What can I do for you?” asked

the portress.

Simonne begged her to send La Faloise out to her. But Mme Bron was

unable to comply with her wishes all at once. Under the stairs in a

sort of deep cupboard she kept a little bar, whither the supers were

wont to descend for drinks between the acts, and seeing that just at

that moment there were five or six tall lubbers there who, still

dressed as Boule Noire masqueraders, were dying of thirst and in a

great hurry, she lost her head a bit. A gas jet was flaring in the

cupboard, within which it was possible to descry a tin-covered table

and some shelves garnished with half-emptied bottles. Whenever the

door of this coalhole was opened a violent whiff of alcohol mingled

with the scent of stale cooking in the lodge, as well as with the

penetrating scent of the flowers upon the table.

“Well now,” continued the portress when she had served the supers,

“is it the little dark chap out there you want?”

“No, no; don’t be silly!” said Simonne. “It’s the lanky one by the

side of the stove. Your cat’s sniffing at his trouser legs!”

And with that she carried La Faloise off into the lobby, while the

other gentlemen once more resigned themselves to their fate and to

semisuffocation and the masqueraders drank on the stairs and

indulged in rough horseplay and guttural drunken jests.

On the stage above Bordenave was wild with the sceneshifters, who

seemed never to have done changing scenes. They appeared to be

acting of set purpose—the prince would certainly have some set

piece or other tumbling on his head.

“Up with it! Up with it!” shouted the foreman.

At length the canvas at the back of the stage was raised into

position, and the stage was clear. Mignon, who had kept his eye on

Fauchery, seized this opportunity in order to start his pummeling

matches again. He hugged him in his long arms and cried:

“Oh, take care! That mast just missed crushing you!”

And he carried him off and shook him before setting him down again.

In view of the sceneshifters’ exaggerated mirth, Fauchery grew

white. His lips trembled, and he was ready to flare up in anger

while Mignon, shamming good nature, was clapping him on the shoulder

with such affectionate violence as nearly to pulverize him.

“I value your health, I do!” he kept repeating. “Egad! I should be

in a pretty pickle if anything serious happened to you!”

But just then a whisper ran through their midst: “The prince! The

prince! And everybody turned and looked at the little door which

opened out of the main body of the house. At first nothing was

visible save Bordenave’s round back and beefy neck, which bobbed

down and arched up in a series of obsequious obeisances. Then the

prince made his appearance. Largely and strongly built, light of

beard and rosy of hue, he was not lacking in the kind of distinction

peculiar to a sturdy man of pleasure, the square contours of whose

limbs are clearly defined by the irreproachable cut of a frock coat.

Behind him walked Count Muffat and the Marquis de Chouard, but this

particular corner of the theater being dark, the group were lost to

view amid huge moving shadows.

In order fittingly to address the son of a queen, who would someday

occupy a throne, Bordenave had assumed the tone of a man exhibiting

a bear in the street. In a voice tremulous with false emotion he

kept repeating:

“If His Highness will have the goodness to follow me—would His

Highness deign to come this way? His Highness will take care!”

The prince did not hurry in the least. On the contrary, he was

greatly interested and kept pausing in order to look at the

sceneshifters’ maneuvers. A batten had just been lowered, and the

group of gaslights high up among its iron crossbars illuminated the

stage with a wide beam of light. Muffat, who had never yet been

behind scenes at a theater, was even more astonished than the rest.

An uneasy feeling of mingled fear and vague repugnance took

possession of him. He looked up into the heights above him, where

more battens, the gas jets on which were burning low, gleamed like

galaxies of little bluish stars amid a chaos of iron rods,

connecting lines of all sizes, hanging stages and canvases spread

out in space, like huge cloths hung out to dry.

“Lower away!” shouted the foreman unexpectedly.

And the prince himself had to warn the count, for a canvas was

descending. They were setting the scenery for the third act, which

was the grotto on Mount Etna. Men were busy planting masts in the

sockets, while others went and took frames which were leaning

against the walls of the stage and proceeded to lash them with

strong cords to the poles already in position. At the back of the

stage, with a view to producing the bright rays thrown by Vulcan’s

glowing forge, a stand had been fixed by a limelight man, who was

now lighting various burners under red glasses. The scene was one

of confusion, verging to all appearances on absolute chaos, but

every little move had been prearranged. Nay, amid all the scurry

the whistle blower even took a few turns, stepping short as he did

so, in order to rest his legs.

“His Highness overwhelms me,” said Bordenave, still bowing low.

“The theater is not large, but we do what we can. Now if His

Highness deigns to follow me—”

Count Muffat was already making for the dressing-room passage. The

really sharp downward slope of the stage had surprised him

disagreeably, and he owed no small part of his present anxiety to a

feeling that its boards were moving under his feet. Through the

open sockets gas was descried burning in the “dock.” Human voices

and blasts of air, as from a vault, came up thence, and, looking

down into the depths of gloom, one became aware of a whole

subterranean existence. But just as the count was going up the

stage a small incident occurred to stop him. Two little women,

dressed for the third act, were chatting by the peephole in the

curtain. One of them, straining forward and widening the hole with

her fingers in order the better to observe things, was scanning the

house beyond.

“I see him,” said she sharply. “Oh, what a mug!”

Horrified, Bordenave had much ado not to give her a kick. But the

prince smiled and looked pleased and excited by the remark. He

gazed warmly at the little woman who did not care a button for His

Highness, and she, on her part, laughed unblushingly. Bordenave,

however, persuaded the prince to follow him. Muffat was beginning

to perspire; he had taken his hat off. What inconvenienced him most

was the stuffy, dense, overheated air of the place with its strong,

haunting smell, a smell peculiar to this part of a theater, and, as

such, compact of the reek of gas, of the glue used in the

manufacture of the scenery, of dirty dark nooks and corners and of

questionably clean chorus girls. In the passage the air was still

more suffocating, and one seemed to breathe a poisoned atmosphere,

which was occasionally relieved by the acid scents of toilet waters

and the perfumes of various soaps emanating from the dressing rooms.

The count lifted his eyes as he passed and glanced up the staircase,

for he was well-nigh startled by the keen flood of light and warmth

which flowed down upon his back and shoulders. High up above him

there was a clicking of ewers and basins, a sound of laughter and of

people calling to one another, a banging of doors, which in their

continual opening and shutting allowed an odor of womankind to

escape—a musky scent of oils and essences mingling with the natural

pungency exhaled from human tresses. He did not stop. Nay, he

hastened his walk: he almost ran, his skin tingling with the breath

of that fiery approach to a world he knew nothing of.

“A theater’s a curious sight, eh?” said the Marquis de Chouard with

the enchanted expression of a man who once more finds himself amid

familiar surroundings.

But Bordenave had at length reached Nana’s dressing room at the end

of the passage. He quietly turned the door handle; then, cringing

again:

“If His Highness will have the goodness to enter—”

They heard the cry of a startled woman and caught sight of Nana as,

stripped to the waist, she slipped behind a curtain while her

dresser, who had been in the act of drying her, stood, towel in air,

before them.

“Oh, it IS silly to come in that way!” cried Nana from her hiding

place. “Don’t come in; you see you mustn’t come in!”

Bordenave did not seem to relish this sudden flight.

“Do stay where you were, my dear. Why, it doesn’t matter,” he said.

“It’s His Highness. Come, come, don’t be childish.”

And when she still refused to make her appearance—for she was

startled as yet, though she had begun to laugh—he added in peevish,

paternal tones:

“Good heavens, these gentlemen know perfectly well what a woman

looks like. They won’t eat you.”

“I’m not so sure of that,” said the prince wittily.

With that the whole company began laughing in an exaggerated manner

in order to pay him proper court.

“An exquisitely witty speech—an altogether Parisian speech,” as

Bordenave remarked.

Nana vouchsafed no further reply, but the curtain began moving.

Doubtless she was making up her mind. Then Count Muffat, with

glowing cheeks, began to take stock of the dressing room. It was a

square room with a very low ceiling, and it was entirely hung with a

light-colored Havana stuff. A curtain of the same material depended

from a copper rod and formed a sort of recess at the end of the

room, while two large windows opened on the courtyard of the theater

and were faced, at a distance of three yards at most, by a leprous-looking wall against which the panes cast squares of yellow light

amid the surrounding darkness. A large dressing glass faced a white

marble toilet table, which was garnished with a disorderly array of

flasks and glass boxes containing oils, essences and powders. The

count went up to the dressing glass and discovered that he was

looking very flushed and had small drops of perspiration on his

forehead. He dropped his eyes and came and took up a position in

front of the toilet table, where the basin, full of soapy water, the

small, scattered, ivory toilet utensils and the damp sponges,

appeared for some moments to absorb his attention. The feeling of

dizziness which he had experienced when he first visited Nana in the

Boulevard Haussmann once more overcame him. He felt the thick

carpet soften under foot, and the gasjets burning by the dressing

table and by the glass seemed to shoot whistling flames about his

temples. For one moment, being afraid of fainting away under the

influence of those feminine odors which he now re-encountered,

intensified by the heat under the low-pitched ceiling, he sat down

on the edge of a softly padded divan between the two windows.

Comments (0)