Outward Bound Or, Young America Afloat: A Story of Travel and Adventure by Optic (popular e readers .TXT) 📗

- Author: Optic

Book online «Outward Bound Or, Young America Afloat: A Story of Travel and Adventure by Optic (popular e readers .TXT) 📗». Author Optic

The Young America had safely ridden out the gale, for all that human art could do to make her safe and strong had been done without regard to expense. No niggardly owners had built her of poor and insufficient material, or sent her to sea weakly manned and with incompetent officers. The ship was heavily manned; eighteen or twenty men would have been deemed a sufficient crew to work her; and though her force consisted of boys, they would average more than two thirds of the muscle and skill of able-bodied seamen.

There were other ships abroad on the vast ocean, which could not compare with her in strength and appointments, and which had not one third of her working power on board. No ship can absolutely defy the elements, and there is no such thing as absolute safety in a voyage across the ocean; but there is far less peril than people who have had no experience generally suppose. The Cunard steamers have been running more than a quarter of a century, with the loss of only one ship, and no lives in that one—a triumphant result achieved by strong ships, with competent men to manage them. Poorly built ships, short manned, with officers unfit for their positions, constitute the harvest of destruction on the ocean.

Mr. Lowington believed that the students of the Academy Ship would be as safe on board the Young {245} America as they would on shore. He had taken a great deal of pains to demonstrate his theory to parents, and though he often failed, he often succeeded. The Young America had just passed through one of the severest gales of the year, and in cruising for the next three years, she would hardly encounter a more terrific storm. She had safely weathered it; the boys had behaved splendidly, and not one of them had been lost, or even injured, by the trying exposure. The principal's theory was thus far vindicated.

The starboard watch piped to breakfast, when the sail was discovered, too far off to make her out. The boys all manifested a deep interest in the distant wanderer on the tempestuous sea, mingled with a desire to know how the stranger had weathered the gale. Many of them went up the shrouds into the tops, and the spy-glasses were in great demand.

"Do you make her out, Captain Gordon?" asked Mr. Fluxion, as he came up from his breakfast, and discovered the commander watching the stranger through the glass.

"Yes, sir; I can just make her out now. Her foremast and mainmast have gone by the board, and she has the ensign, union down, hoisted at her mizzen," replied the captain, with no little excitement in his manner.

"Indeed!" exclaimed the teacher of mathematics, as he took the glass. "You are right, Captain Gordon, and you had better keep her away."

"Shall I speak to Mr. Lowington first, sir?" asked the captain.

"I think there is no need of it in the present {246} instance. There can be no doubt what he will do when a ship is in distress."

"Mr. Kendall, keep her away two points," said the captain to the officer of the deck. "What is the ship's course now?"

"East-south-east, sir," replied the second lieutenant, who had the deck.

"Make it south-east."

"South-east, sir," repeated Kendall. "Quartermaster keep her away two points," he added to the petty officer conning the wheel.

"Two points, sir," said Bennington, the quartermaster

"Make the course south-east."

"South-east, sir."

After all these repetitions it was not likely that any mistake would occur; and the discipline of the ship required every officer and seaman who received a material order, especially in regard to the helm or the course, to repeat it, and thus make sure that it was not misunderstood.

It was Sunday; and no study was required, or work performed, except the necessary ship's duty. Morning prayers had been said, as usual, and there was to be divine service in the steerage, forenoon and afternoon, for all who could possibly attend; and this rule excepted none but the watch on deck. By this system, the quarter watch on duty in the forenoon, attended in the afternoon; those who were absent at morning prayers were always present at the evening devotions; and blow high or blow low, the brief matin and vesper service were never omitted, for young men in the midst {247} of the sublimity and the terrors of the ocean could least afford to be without the daily thought of God, "who plants his footsteps in the sea, and rides upon the storm."

Every man and boy in the ship was watching the speck on the watery waste, which the glass had revealed to be a dismasted, and perhaps sinking ship. The incident created an intense interest, and was calculated to bring out the finer feelings of the students. They were full of sympathy for her people, and the cultivation of noble and unselfish sentiments, which the occasion had already called forth, and was likely to call forth in a still greater degree, was worth the voyage over the ocean; for there are impressions to be awakened by such a scene which can be garnered in no other field.

CHAPTER XVI.{248}

THE WRECK OF THE SYLVIA.Return to Table of Contents

The people in the dismasted ship had discovered the Young America, as it appeared from the efforts they were using to attract her attention. The booming of a gun was occasionally heard from her, but she was yet too far off to be distinctly seen.

On the forecastle of the Academy Ship were two brass guns, four-pounders, intended solely for use in making signals. They had never been fired, even on the Fourth of July, for Mr. Lowington would not encourage their use among the boys. On the present occasion he ordered Peaks, the boatswain, to fire twice, to assure the ship in distress that her signals were heard.

The top-gallant sails were set, and the speed of the ship increased as much as possible; but the heavy sea was not favorable to rapid progress through the water. At four bells, when all hands but the second part of the port watch were piped to attend divine service in the steerage, the Young America was about four miles distant from the dismasted vessel. She was rolling and pitching heavily, and not making more than two or three knots an hour.

Notwithstanding the impatience of the crew, and {249} their desire to be on deck, where they could see the wreck, the service on that Sunday forenoon was especially impressive. Mr. Agneau prayed earnestly for those who were suffering by the perils of the sea, and that those who should draw near unto them in the hour of their danger, might be filled with the love of God and of man, which would inspire them to be faithful to the duties of the occasion.

When the service was ended the students went on deck again. The wreck could now be distinctly seen. It was a ship of five or six hundred tons, rolling helplessly in the trough of the sea. She was apparently water-logged, if not just ready to go down. As the Young America approached her, her people were seen to be laboring at the pumps, and to be baling her out with buckets. It was evident from the appearance of the wreck, that it had been kept afloat only by the severest exertion on the part of the crew.

"Mr. Peaks, you will see that the boats are in order for use," said Mr. Lowington. "We shall lower the barge and the gig."

"The barge and the gig, sir," replied the boatswain.

"Captain Gordon," continued the principal, "two of your best officers must be detailed for the boats."

"I will send Mr. Kendall in the barge, sir."

"Very well; he is entirely reliable. Whom will you send in the gig?"

"I am sorry Shuffles is not an officer now, for he was one of the best we had for such service," added the captain.

"Shuffles is out of the question," replied Mr. Lowington. {250}

"Mr. Haven, then, in the gig."

"The sea is very heavy, and the boats must be handled with skill and prudence."

"The crews have been practised in heavy seas, though in nothing like this."

The barge and the gig—called so by courtesy—were the two largest boats belonging to the ship, and pulled eight oars each. They were light and strong, and had been built with especial reference to the use for which they were intended. They were life-boats, and before the ship sailed, they had been rigged with life-lines and floats. If they were upset in a heavy sea, the crews could save themselves by clinging to the rope, buoyed up by the floats.

The Young America stood up towards the wreck, intending to pass under her stern as near as it was prudent to lay, the head of the dismasted ship being to the north-west.

"Boatswain, pipe all hands to muster," said the captain, prompted by Mr. Lowington, as the ship approached the wreck.

"All hands on deck, ahoy!" shouted the boatswain, piping the call.

The first lieutenant took the trumpet from the officer of the deck, and the crew, all of whom were on deck when the call was sounded, sprang to their muster stations.

"All hands, take in courses," said the executive officer; and those who were stationed at the tacks and sheets, clew-garnets and buntlines, prepared to do their duty when the boatswain piped the call.

"Man the fore and main clew-garnets and bunt {251}lines!" shouted the first lieutenant. "Stand by tacks and sheets!"

The fore and main sail, being the lowest square sails, are called the courses. There is no corresponding sail on the mizzenmast. The ropes by which the lower corners of these sails are hauled up for furling are the clew-garnets—the same that are designated clewlines on the topsails.

The tacks and sheets are the ropes by which the courses are hauled down, and kept in place, the tack being on the windward side, and the sheet on the leeward.

"All ready, sir," reported the lieutenants forward.

"Haul taut! Let go tacks and sheets! Haul up!"

These orders being promptly obeyed, the courses were hauled up, and the ship was under topsails and top-gallant sails, jib, flying-jib, and spanker.

"Ship, ahoy!" shouted the first lieutenant through his trumpet, as the Young America rolled slowly along under the stern of the wreck.

"Ship, ahoy!" replied a voice from the deck of the wreck. "We are in a sinking condition! Will you take us off?"

"Ay, ay!" cried Haven, with right good will.

"You will heave to the ship, Mr. Haven," said the captain, when she had passed a short distance beyond the wreck.

"Man the jib and flying-jib halyards and down-hauls," said the first lieutenant.

"All ready forward, sir," replied the second lieutenant, on the forecastle. {252}

"Stand by the maintop bowline! Cast off! Man the main braces!"

"Let go the jib and flying-jib halyards! Haul down!" And the jibs were taken in.

"Slack off the lee braces! Haul on the weather braces!"

The main-topsail and top-gallant were thus thrown aback, and the Young America was hove to, in order to enable her people to perform their humane mission.

"Stand by to lower the barge and gig!" continued Haven.

"Mr. Haven, you will board the wreck in the gig," said Captain Gordon.

"Yes, sir," replied he, touching his cap, and handing the trumpet to the second lieutenant.

"Mr. Kendall, you will take charge of the barge," added the captain.

"The barge, sir," answered Kendall, passing the trumpet to Goodwin, the third lieutenant, who, during the absence of his superiors, was to discharge the duty of the executive officer.

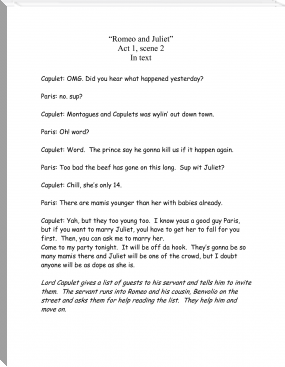

The Wreck of the Sylvia.

Return to List of Illustrations

The boats were cleared away, and every preparation made for lowering them into the water. This was a difficult and dangerous manoeuvre in the heavy sea which was running at the time. The professors' barge, which was secured at the davits on the weather side of the ship, was to be lowered with her crew on board, and they took their places on the thwarts, with their hands to the oars in readiness for action. The principal had requested Mr. Fluxion to go in the barge and Mr. Peaks in the gig, not to command the {253}boats, but to give the officers such suggestions as the emergency of the occasion might require.

"All ready, sir," reported Ward, the coxswain of the barge, when the oarsmen were in their places.

"Stand by the after tackle, Ward," said Haven. "Bowman, attend to the fore tackle."

At a favorable moment, when a great wave was sinking down by the ship's side, the order was given to lower away, and in an instant the barge struck the water. Ward cast off the after tackle, and

Comments (0)