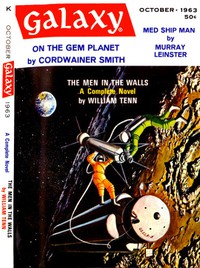

Med Ship Man by Murray Leinster (have you read this book txt) 📗

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «Med Ship Man by Murray Leinster (have you read this book txt) 📗». Author Murray Leinster

He stared up. He saw a parachute blossom as a bare speck against the blue. Then he heard the even deeper-toned roaring of a supersonic craft climbing skyward. It could be a spaceliner's lifeboat, descended into atmosphere and going out again.

It was. It had left a parachute behind, and now went back to space to rendezvous with its parent ship.

"That," said Calhoun impatiently, "will be the Candida's passenger. He was insistent enough."

He scowled. The Candida's voice had said its passenger demanded to be landed for business reasons. And Calhoun had a prejudice against some kinds of business men who would think their own affairs more important than anything else. Two standard years before, he'd made a planetary health inspection on Texia II, in another galactic sector. It was a llano planet and a single giant business enterprise. Illimitable prairies had been sown with an Earth-type grass which destroyed the native ground-cover—the reverse of the ground-cover situation here—and the entire planet was a monstrous range for beef cattle. Dotted about were gigantic slaughterhouses, and cattle in masses of tens of thousands were shifted here and there by ground-induction fields which acted as fences. Ultimately the cattle were driven by these same induction fences to the slaughter houses and actually into the chutes where their throats were slit. Every imaginable fraction of a credit of profit was extracted from their carcasses, and Calhoun had found it appalling.

He was not sentimental about cattle, but the complete cold-bloodedness of the entire operation sickened him. The same cold-bloodedness was practised toward the human employees who ran the place. Their living quarters were sub-marginal. The air stank of cattle murder. Men worked for the Texia Company or they did not work. If they did not work they did not eat. If they worked and ate,—Calhoun could see nothing satisfying in being alive on a world like that! His report to Med Service had been biting. He'd been prejudiced against businessmen ever since.

But a parachute descended, blowing away from the city. It would land not too far from the highway he followed. And it didn't occur to Calhoun not to help the unknown chutist. He saw a small figure dangling below the chute. He slowed the ground-car as he estimated where the parachute would land.

He was off the twelve-lane highway and on a feeder road when the chute was a hundred feet high. He was racing across a field of olive-green plants that went all the way to the horizon when the parachute actually touched ground. There was a considerable wind. The man in the harness bounced. He didn't know how to spill the air. The chute dragged him.

Calhoun sped ahead, swerved and ran into the chute. He stopped the car and the chute stopped with it. He got out.

The man lay in a hopeless tangle of cordage. He thrust unskilfully at it. When Calhoun came up he said suspiciously:

"Have you a knife?"

Calhoun offered a knife, politely opening its blade. The man slashed at the cords and freed himself. There was an attache case lashed to his chute harness. He cut at those cords. The attache case not only came clear, but opened. It dumped out an incredible mass of brand new, tightly packed interstellar credit certificates. Calhoun could see that the denominations were one thousand and ten thousand credits. The man from the chute reached under his armpit and drew out a blaster.

It was not a service weapon. It was elaborate, practically a toy. With a dour glance at Calhoun he put it in a side pocket and gathered up the scattered money. It was an enormous sum, but he packed it back. He stood up.

"My name is Allison," he said in an authoritative voice. "Arthur Allison. I'm much obliged. Now I'll ask you to take me to Maya City."

"No," said Calhoun politely. "I just left there. It's deserted. I'm not going back. There's nobody there."

"But I've important bus—" The other man stared. "It's deserted? But that's impossible!"

"Quite," agreed Calhoun, "but it's true. It's abandoned. Uninhabited. Everybody's left it. There's no one there at all."

The man who called himself Allison blinked unbelievingly. He swore. Then he raged profanely.

But he was not bewildered by the news. Which, upon consideration, was itself almost bewildering. But then his eyes grew shrewd. He looked about him.

"My name is Allison," he repeated, as if there were some sort of magic in the word. "Arthur Allison. No matter what's happened, I've some business to do here. Where have the people gone? I need to find them."

"I need to find them too," said Calhoun. "I'll take you with me, if you like."

"You've heard of me." It was a statement, confidently made.

"Never," said Calhoun politely. "If you're not hurt, suppose you get in the car? I'm as anxious as you are to find out what's happened. I'm Med Service."

Allison moved toward the car.

"Med Service, eh? I don't think much of the Med Service! You people try to meddle in things that are none of your business!"

Calhoun did not answer. The muddy man, clutching the attache case tightly, waded through the olive-green plants to the car and climbed in. Murgatroyd said cordially, "Chee-chee!" but Allison viewed him with distaste.

"What's this?"

"He's Murgatroyd," said Calhoun. "He's a tormal. He's Med service personnel."

"I don't like beasts," said Allison coldly.

"He's much more important to me than you are," said Calhoun, "if the matter should come to a test."

Allison stared at him as if expecting him to cringe. Calhoun did not. Allison showed every sign of being an important man who expected his importance to be recognized and catered to. When Calhoun stirred impatiently he got into the car and growled a little. Calhoun took his place. The ground-car hummed. It rose on the six columns of air which took the place of wheels and slid across the field of dark-green plants, leaving the parachute deflated across a number of rows, and a trail of crushed-down plants where it had moved.

It reached the highway again. Calhoun ran the car up on the highway's shoulder, and then suddenly checked. He'd noticed something.

He stopped the car and got out. Where the ploughed field ended, and before the coated surface of the highway began, there was a space where on another world one would expect to see green grass.

On this planet grass did not grow; but there would normally be some sort of self-planted vegetation where there was soil and sunshine and moisture. There had been such vegetation here, but now there was only a thin, repellent mass of slimy and decaying foliage. Calhoun bent down to it.

It had a sour, faintly astringent smell of decay. These were the ground-cover plants of Maya of which Calhoun had read. They had motile stems, leaves and flowers, and they had cannibalistic tendencies. They were the local weeds which made it impossible to grow grain for human use upon this world.

And they were dead.

Calhoun straightened up and returned to the car. Plants like this were wilted at the base of the spaceport building, and on another place where there should have been sward. Calhoun had seen a large dead member of the genus in a florist's, that had been growing in a cage before it died. There was a singular coincidence here: humans ran away from something, and something caused the death of a particular genus of cannibal weeds.

It did not exactly add up to anything in particular, and certainly wasn't evidence for anything at all. But Calhoun drove on in a vaguely puzzled mood. The germ of a guess was forming in his mind. He couldn't pretend to himself that it was likely, but it was surely no more unlikely than most of a million human beings abandoning their homes at a moment's notice.

III

They came to the turnoff for a town called Tenochitlan, some forty miles from Maya City. Calhoun swung off the highway to go through it.

Whoever had chosen the name Maya for this planet had been interested in the legends of Yucatan, back on Earth. There were many instances of such hobbies in a Med Ship's list of ports of call. Calhoun touched ground regularly on planets that had been named for countries and towns when men first roamed the stars, and nostalgically christened their discoveries with names suggested by homesickness. There was a Tralee, and a Dorset, and an Eire. Colonists not infrequently took their world's given name as a pattern and chose related names for seas and peninsulas and mountain chains. On Texia the landing-grid rose near a town called Corral and the principal meat-packing settlement was named Roundup.

Whatever the name Tenochitlan would have suggested, though, was denied by the town itself. It was small, with a pleasing local type of architecture. There were shops and some factories, and many strictly private homes, some clustered close together and others in the middles of considerable gardens. In those gardens also there was wilt and decay among the cannibal plants. There was no grass, because the plants prevented it, but now the motile plants themselves were dead. Except for the one class of killed growing things, however, vegetation was luxuriant.

But the little city was deserted. Its streets were empty, its houses untenanted. Some houses were apparently locked up here, though, and Calhoun saw three or four shops whose stock in trade had been covered over before the owners departed. He guessed that either this town had been warned earlier than the spaceport city, or else they knew they had time to get in motion before the highways were filled with the cars from the west.

Allison looked at the houses with keen, evaluating eyes. He did not seem to notice the absence of people. When Calhoun swung back on the great road beyond the little city, Allison regarded the endless fields of dark-green plants with much the same sort of interest.

"Interesting," he said abruptly when Tenochitlan fell behind and dwindled to a speck. "Very interesting! I'm interested in land. Real property, that's my business. I've a land-owning corporation on Thanet Three. I've some holdings on Dorset, too, and elsewhere. It just occurred to me: what's all this land and the cities worth, with the people all run away?"

"What," asked Calhoun, "are the people worth who've run?"

Allison paid no attention. He looked shrewd. Thoughtful.

"I came here to buy land," he said. "I'd arranged to buy some hundreds of square miles. I'd buy more if the price were right. But—as things are, it looks like the price of land ought to go down quite a bit. Quite a bit!"

"It depends," said Calhoun, "on whether there's anybody left alive to sell it to you, and what sort of thing has happened."

Allison looked at him sharply.

"Ridiculous!" he said authoritatively. "There's no question of their being alive!"

"They thought there might be," observed Calhoun. "That's why they ran away. They hoped they'd be safe where they ran to. I hope they are."

Allison ignored the comment. His eyes remained intent and shrewd. He was not bewildered by the flight of the people of Maya. His mind was busy with contemplation of that flight from the standpoint of a man of business.

The car went racing onward. The endless fields of dark green rushed past to the rear. The highway was deserted, just three strips of surfaced road, mathematically straight, going on to the horizon. They went on by tens and scores of miles, each strip wide enough to allow four ground-cars to run side by side. The highway was intended to allow all the produce of all these fields to be taken to market or a processing plant at the highest possible speed and in any imaginable quantity. The same roads had allowed the cities to be deserted instantly the warning—whatever the warning was—arrived.

Fifty miles beyond Tenochitlan there was a mile-long strip of sheds containing agricultural machinery for crop culture and trucks to carry the crops to market. There was no sign of life about the machinery, nor in a further hour's run to westward.

Then there was a city visible to the left. But it was not served by this particular highway, but another. There was no sign of any movement in its streets. It moved along the horizon to the left and rear. Presently it disappeared.

Half an hour later still, Murgatroyd said:

"Chee!"

He stirred uneasily. A moment later he said "Chee!" again.

Calhoun turned his eyes from the road. Murgatroyd looked unhappy. Calhoun ran his hand over the tormal's furry body. Murgatroyd pressed against him. The car raced on. Murgatroyd whimpered a little. Calhoun's hand felt the little animal's muscles tense sharply, and then relax, and after a little tense again. Murgatroyd said almost hysterically:

"Chee-chee-chee-chee!"

Calhoun

Comments (0)