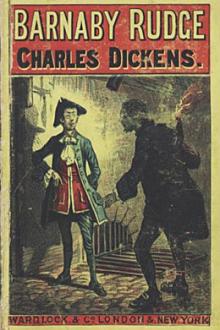

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗

- Author: Charles Dickens

Book online «Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗». Author Charles Dickens

‘A devil, a devil, a devil!’ cried a hoarse voice.

‘Here’s money!’ said Barnaby, chinking it in his hand, ‘money for a treat, Grip!’

‘Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!’ replied the raven, ‘keep up your spirits. Never say die. Bow, wow, wow!’

Mr Willet, who appeared to entertain strong doubts whether a customer in a laced coat and fine linen could be supposed to have any acquaintance even with the existence of such unpolite gentry as the bird claimed to belong to, took Barnaby off at this juncture, with the view of preventing any other improper declarations, and quitted the room with his very best bow.

Chapter 11

There was great news that night for the regular Maypole customers, to each of whom, as he straggled in to occupy his allotted seat in the chimney-corner, John, with a most impressive slowness of delivery, and in an apoplectic whisper, communicated the fact that Mr Chester was alone in the large room upstairs, and was waiting the arrival of Mr Geoffrey Haredale, to whom he had sent a letter (doubtless of a threatening nature) by the hands of Barnaby, then and there present.

For a little knot of smokers and solemn gossips, who had seldom any new topics of discussion, this was a perfect Godsend. Here was a good, dark-looking mystery progressing under that very roof—brought home to the fireside, as it were, and enjoyable without the smallest pains or trouble. It is extraordinary what a zest and relish it gave to the drink, and how it heightened the flavour of the tobacco. Every man smoked his pipe with a face of grave and serious delight, and looked at his neighbour with a sort of quiet congratulation. Nay, it was felt to be such a holiday and special night, that, on the motion of little Solomon Daisy, every man (including John himself) put down his sixpence for a can of flip, which grateful beverage was brewed with all despatch, and set down in the midst of them on the brick floor; both that it might simmer and stew before the fire, and that its fragrant steam, rising up among them, and mixing with the wreaths of vapour from their pipes, might shroud them in a delicious atmosphere of their own, and shut out all the world. The very furniture of the room seemed to mellow and deepen in its tone; the ceiling and walls looked blacker and more highly polished, the curtains of a ruddier red; the fire burnt clear and high, and the crickets in the hearthstone chirped with a more than wonted satisfaction.

There were present two, however, who showed but little interest in the general contentment. Of these, one was Barnaby himself, who slept, or, to avoid being beset with questions, feigned to sleep, in the chimney-corner; the other, Hugh, who, sleeping too, lay stretched upon the bench on the opposite side, in the full glare of the blazing fire.

The light that fell upon this slumbering form, showed it in all its muscular and handsome proportions. It was that of a young man, of a hale athletic figure, and a giant’s strength, whose sunburnt face and swarthy throat, overgrown with jet black hair, might have served a painter for a model. Loosely attired, in the coarsest and roughest garb, with scraps of straw and hay—his usual bed—clinging here and there, and mingling with his uncombed locks, he had fallen asleep in a posture as careless as his dress. The negligence and disorder of the whole man, with something fierce and sullen in his features, gave him a picturesque appearance, that attracted the regards even of the Maypole customers who knew him well, and caused Long Parkes to say that Hugh looked more like a poaching rascal to-night than ever he had seen him yet.

‘He’s waiting here, I suppose,’ said Solomon, ‘to take Mr Haredale’s horse.’

‘That’s it, sir,’ replied John Willet. ‘He’s not often in the house, you know. He’s more at his ease among horses than men. I look upon him as a animal himself.’

Following up this opinion with a shrug that seemed meant to say, ‘we can’t expect everybody to be like us,’ John put his pipe into his mouth again, and smoked like one who felt his superiority over the general run of mankind.

‘That chap, sir,’ said John, taking it out again after a time, and pointing at him with the stem, ‘though he’s got all his faculties about him—bottled up and corked down, if I may say so, somewheres or another—’

Original

‘Very good!’ said Parkes, nodding his head. ‘A very good expression, Johnny. You’ll be a tackling somebody presently. You’re in twig to-night, I see.’

‘Take care,’ said Mr Willet, not at all grateful for the compliment, ‘that I don’t tackle you, sir, which I shall certainly endeavour to do, if you interrupt me when I’m making observations.—That chap, I was a saying, though he has all his faculties about him, somewheres or another, bottled up and corked down, has no more imagination than Barnaby has. And why hasn’t he?’

The three friends shook their heads at each other; saying by that action, without the trouble of opening their lips, ‘Do you observe what a philosophical mind our friend has?’

‘Why hasn’t he?’ said John, gently striking the table with his open hand. ‘Because they was never drawed out of him when he was a boy. That’s why. What would any of us have been, if our fathers hadn’t drawed our faculties out of us? What would my boy Joe have been, if I hadn’t drawed his faculties out of him?—Do you mind what I’m a saying of, gentlemen?’

‘Ah! we mind you,’ cried Parkes. ‘Go on improving of us, Johnny.’

‘Consequently, then,’ said Mr Willet, ‘that chap, whose mother was hung when he was a little boy, along with six others, for passing bad notes—and it’s a blessed thing to think how many people are hung in batches every six weeks for that, and such like offences, as showing how wide awake our government is—that chap that was then turned loose, and had to mind cows, and frighten birds away, and what not, for a few pence to live on, and so got on by degrees to mind horses, and to sleep in course of time in lofts and litter, instead of under haystacks and hedges, till at last he come to be hostler at the Maypole for his board and lodging and a annual trifle—that chap that can’t read nor write, and has never had much to do with anything but animals, and has never lived in any way but like the animals he has lived among, IS a animal. And,’ said Mr Willet, arriving at his logical conclusion, ‘is to be treated accordingly.’

‘Willet,’ said Solomon Daisy, who had exhibited some impatience at the intrusion of so unworthy a subject on their more interesting theme, ‘when Mr Chester come this morning, did he order the large room?’

‘He signified, sir,’ said John, ‘that he wanted a large apartment. Yes. Certainly.’

‘Why then, I’ll tell you

Comments (0)